Professor Tom Spencer investigates a photograph in the archives of the Royal Society: what event brought these three individuals together, when, and where?

When items from the estate of Brian Morton (biographer of Sir Maurice Yonge FRS) arrived at the Royal Society’s archives in April 2021, they included some loose photographs. One of these shows three individuals ‘in the field’; the back of the photo reveals them to be Henry Pilsbry, Charles Hedley and Matthew Nathan. But there is no further annotation. What event brought these three individuals together? When was the photo taken? And where?

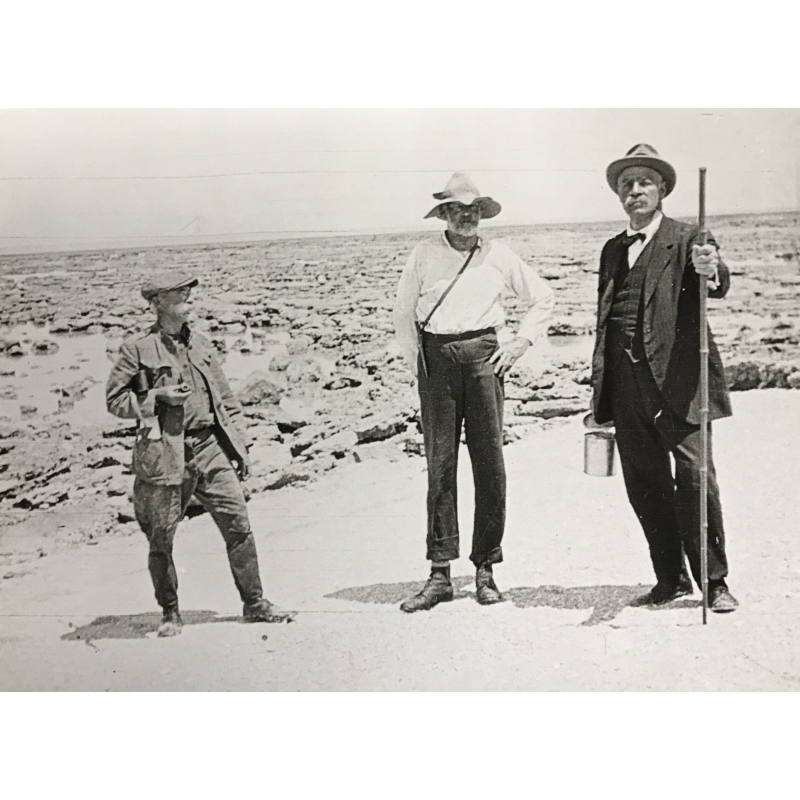

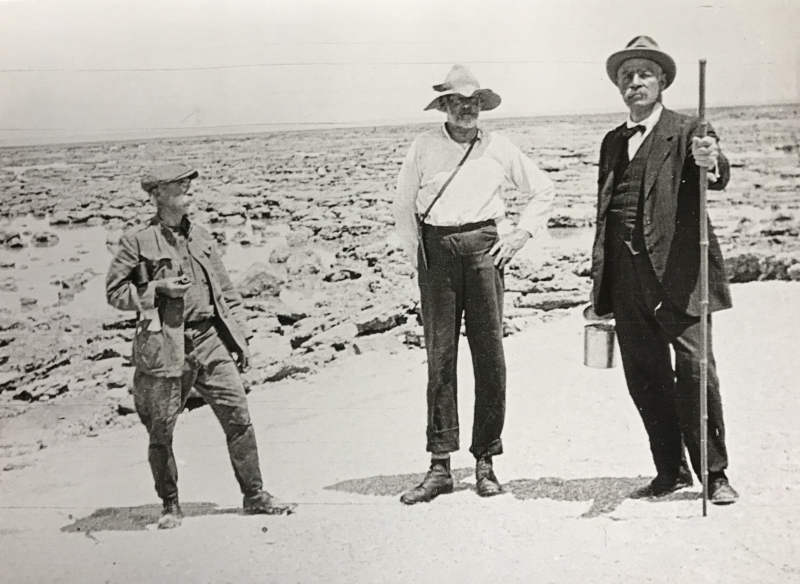

Three men on a reef (L-R) Henry Pilsbry, Charles Hedley and Matthew Nathan (Royal Society MS/940)

Three men on a reef (L-R) Henry Pilsbry, Charles Hedley and Matthew Nathan (Royal Society MS/940)

Sir Matthew Nathan (1862-1939) was Governor of Queensland between December 1920 and September 1925. He was one of the driving forces behind Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Committee (GBRC), founded in Brisbane on 12 September 1922. Charles Hedley (1862-1926), a naturalist with a particular interest in molluscs, was appointed to the staff of the Australian Museum in 1891, rising to become principal keeper of collections in 1920 before resigning to become Scientific Director of the GBRC in 1925. In 1896, he had accompanied the Royal Society’s expedition to Funafuti, making collections of invertebrates and ethnographic material, alongside the expedition’s primary focus of trying (unsuccessfully) to ‘deep drill’ through the atoll’s coral cap to the underlying volcanic basement.

But the best clues to deciphering the image come from the archives of Henry Pilsbry (1862-1957), an American biologist who also specialised in molluscs. At the age of 25 he had been appointed ‘Conservator of the Conchology Section’ at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (now part of Drexel University), staying there for the rest of his academic life. Now, with the help of Drexel archivists Kelsey Manahan-Phelan and Jessica Lyndon, it has been possible to find the record of the field trip that produced the photograph.

The 1920s were a period of growing interest in a ‘Pacific sense’ and the role of science in providing a unifying framework for international cooperation. The first international meeting of the Pan-Pacific Union (Honolulu, August 1920) was very much an American inspiration but the Australian delegates included Ernest Clayton Andrews, Director of New South Wales Geological Survey, Charles Hedley, and the recently appointed (1919) Professor of Geology at the University of Queensland, Henry Caselli Richards (1884-1947). Heavily promoted by Andrews, the 1923 Pan-Pacific Science Congress in Australia opened in Melbourne on 13 August but then moved on to Sydney under the supervision of geologist Professor Sir T W Edgeworth David FRS. David, an Antarctic hero knighted for his wartime services, had been the organiser of the second and third coral reef drilling attempts on Funafuti.

In the course of the Sydney discussions, Henry Richards issued a set of instructions for a post-conference field excursion to the Great Barrier Reef to a group of 20 scientists. Nathan arranged for the use of the Government steamer Relief to undertake a cruise between Mackay and Cairns, leaving Mackay on 12 September and returning nine days later.

The photograph above, reproduced by kind permission of the John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, shows the September 1923 excursion party on the Relief, with Sir Matthew Nathan against the mast, centre stage. In a typescript entitled A glimpse of Queensland and the Great Barrier Reef of Australia, Pilsbry described the steamer as seaworthy but cramped: ‘when our mattresses were spread for the night you might walk the length of the deck on sleeping scientists’.

Pilsbry’s typescript account of the field trip continued, in lyrical prose which will remind many of their first encounter with a coral reef:

‘The wonderful gardens of living coral are at the edge of the reef. Here a high table of purple porites rises nearly to the surface. Next to it is a tangle of madrepores, yellow with pink tips, and beyond that a mound of massive, green meandrinas … Giant clams, sometimes far heavier than a man can lift, lie gaping open in the pools. Their broad mouths are wonderfully brilliant, blue, green, or purple with green spots, and set with eyes’.

Live individual of Tridacna gigas, with mantle exposed, on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo: Jan Derk, Wikimedia Commons

Live individual of Tridacna gigas, with mantle exposed, on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo: Jan Derk, Wikimedia Commons

Pilsbry concluded:

‘After a session on the reef we would go aboard wet and hungry but happy; those of us with the collecting instinct loaded with “specimens”. But after all, to really learn anything about the animals of the reef one should settle down for a year with microscope and sketch book on one of these charming islands.’

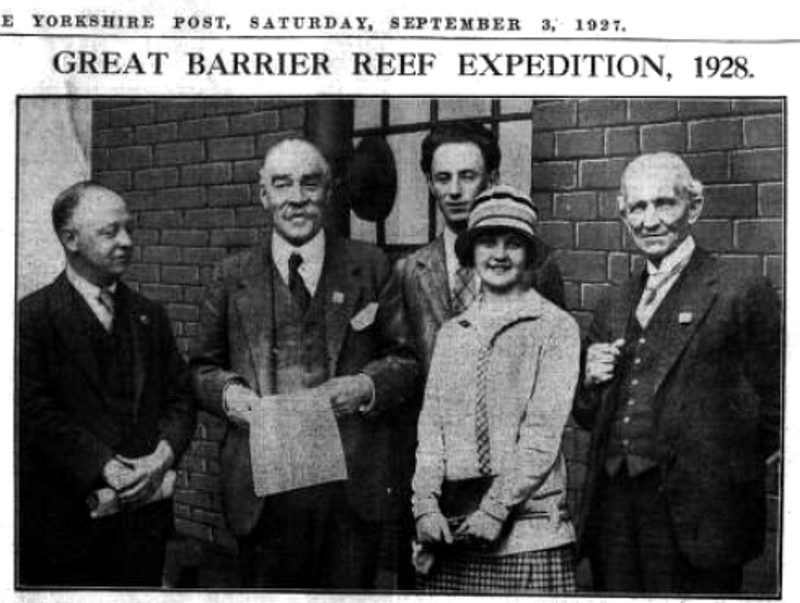

His comment was prophetic. Through the efforts of Richards, Nathan and the Cambridge zoologist J Stanley Gardiner FRS, an expedition to the ‘charming island’ of Low Isles, northern Great Barrier Reef, was formally endorsed at the Leeds meeting of the British Association on 2 September 1927. The picture below shows Francis Potts (an early choice of leader then ruthlessly discarded by Gardiner), Nathan, Maurice Yonge, Mattie Yonge and Edgeworth David:

Source: The Yorkshire Post, 3 September 1927; Papers of Sir Maurice Yonge, Subseries C561-562

Source: The Yorkshire Post, 3 September 1927; Papers of Sir Maurice Yonge, Subseries C561-562

Sadly, Hedley was not present. He had died of a heart attack on 14 September 1926, on the same day as a letter had arrived from Hedley to Henry Richards ‘telling me what a good idea [an] expedition was and how gladly he would co-operate’.

The Great Barrier Reef Expedition took place between July 1928 and July 1929. The Expedition Leader was Dr (later Sir) Maurice Yonge FRS, the Deputy Leader Frederick Russell FRS and the shore party led by T Alan Stephenson FRS. Remarkably, a third of the Expedition’s scientists were women, including Mattie Yonge, Sheina Marshall FRS and Sidnie Manton FRS. The Expedition’s investigations involved meticulous microscopic work and painstaking laboratory and field observation, measurement and experimentation, cataloguing linkages between reef habitats and coral physiology, tidal processes and physical and chemical properties of water.

Fundamentally, by being housed on a single reef and sand cay for a period of 13 months, the Expedition emphasised for the first time the relationships between reef growth and environment and the critical importance of their study in the field. It effectively provided the template for all modern analytical coral reef research.

So three men on a reef, on the Great Barrier Reef north of Mackay, sometime between 12 and 21 September 1923. The exact location is still unclear but Pilsbry did describe Pandora Reef as being ‘piled ten foot high with sand and shell debris’ which would fit with the setting shown in the photograph. And what were they talking about? The first discussions on the form and practice of modern coral reef science.