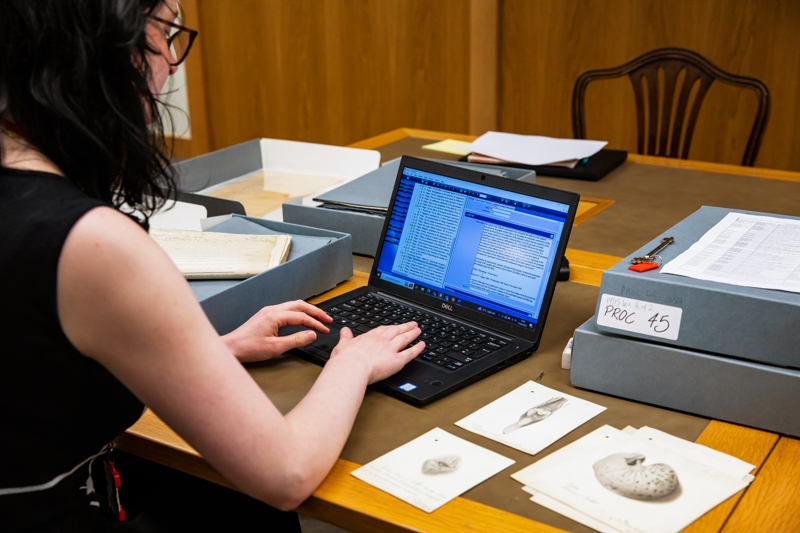

Royal Society Digital Resources Manager Louisiane Ferlier launches our new Science in the Making platform containing treasures from our archives.

Prepare yourselves for a post dripping with adjectives and superlatives.

I’m extremely delighted to be launching the permanent version of our digital archive, Science in the Making. As our Project Manager announced last week, this new website builds on a previous pilot, which was successful in testing the technology, standards and focus we wanted to adopt.

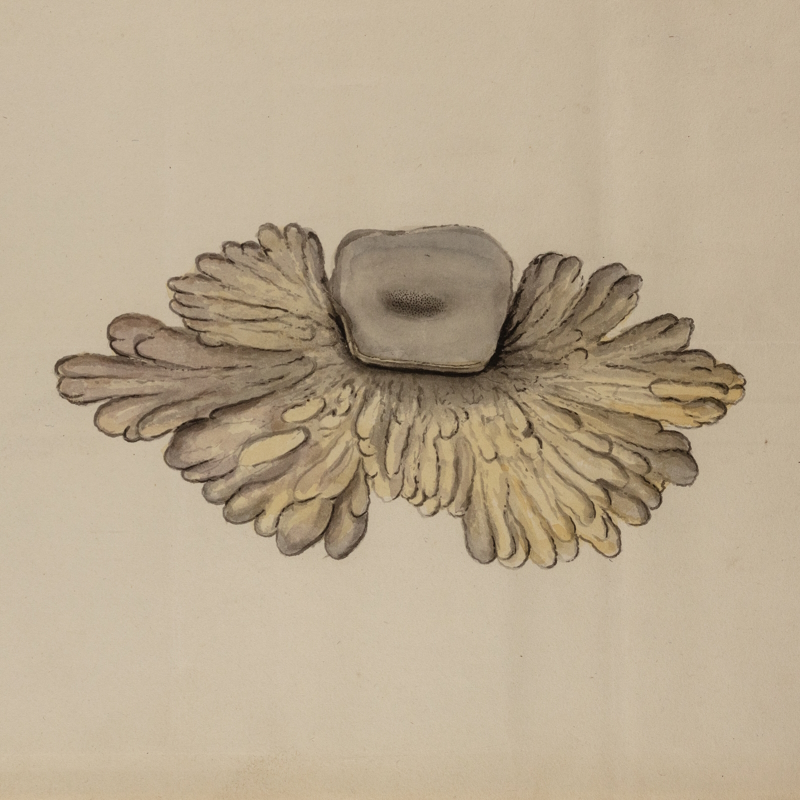

As with the small sample originally contained in the pilot, the whopping 30,000 manuscripts now included in Science in the Making relate to the long history of scientific publishing at the Royal Society. I want to give you a glimpse of the work that has gone on behind the scenes to make the launch of our largest-ever digitisation project possible.

Every single one of these 30,000 manuscripts has been catalogued over the last five years by a succession of incredibly patient archive cataloguers who have described each item in six full archival series. Their work will allow you to search easily through the collection, making connections between manuscripts and with the printed articles on the Royal Society Journals platform.

The cataloguers also identified any items needing conservation care. These were then treated by freelance paper conservators who have improved the health of the collection immensely, by cleaning, repairing, and re-housing the papers. This goes to show that digitisation does not necessarily have a negative impact on a physical collection, if it is seen instead as the opportunity to conserve fragile material to enable improved access, and to preserve it for future generations.

Then we have to thank Bespoke archives digitisation for creating page after page of amazing high-resolution photographs – over 250,000 of them! Again, the challenge was momentous in handling and imaging documents of all sizes. In all we will have generated 45 TB.

As announced last week, the platform itself, beautifully designed and solidly built in partnership with the digital agency Cogapp Ltd, remains free to all. Now, you can even download a PDF of the items to assist your research by clicking on this icon:

Do get in touch if you would like to include any of the images in public-facing work or if you want to play with the underlying data.

All this work started after the pilot launched in 2018, but ground to a halt for nearly a year due to COVID. Still, the statistics for the whole project remain dizzying: in the space of five years and in spite of a pandemic we have managed to go through material covering the whole of modern western science, from Galileo to Dorothy Hodgkin, and from alchemy to quantum physics.

Here are just three of my favourite items, in no particular order:

1. Caroline Herschel is often celebrated for her discoveries of comets and you will find on the platform her original letters describing her observations, but it is her lifelong quest to catalogue the deep skies that fascinates me most, and you can follow her stargazing step by step:

2. The referee’s report by physicist Shelford Bidwell (inventor of a precursor to the fax machine) of a paper on 'The evolution of the colour sense' by Frederick William Edridge-Green in 1900:

Bidwell describes the author as 'a crank', and the paper as 'rubbish of so rank a character that no competent person could possibly take any other view of it'. Edridge-Green's test for colour blindness was nonetheless adopted by the Navy.

3. Some of the letters and papers submitted for review to the Royal Society also contained specimens or samples. In this letter our unsuspecting cataloguer found a dried leaf, unprotected, with no reference to the plant species:

The letter reads:

'Whatever it is, Time will shew, as I have planted a root of it in my garden, and when the leaves are large enough to distinguish the Plant, I shall doe myself the Pleasure to send you one of them.'

A second letter from the sender helpfully points out that this leaf was not hemlock but henbane. Both species are highly poisonous – thankfully our cataloguer remained unharmed, and the specimen is now safely housed in a transparent pocket to protect handlers.

There are countless other amazing tales lurking in the archive, and we’ll undoubtedly share some with you. For us, one measure of success would be seeing new stories emerge through sharing these images with the wider public.

None of this work would have been possible without the support of our Fellowship of scientists, who have understood the thrill of looking through the past to celebrate the giants on whose shoulders we all stand, and also the importance of learning from previous errors.

As with all large projects, this has truly been a team effort. Today I very much feel as a conductor would, standing in front of her orchestra, knowing full well that none of it would have happened without the contribution of each of its members. And so I’ll leave you all to enjoy this video introducing the largest digitisation project conducted at the Royal Society, and I bow to my wonderful team who have made it possible.

Science in the Making is now live, you can email us your thoughts, or tweet us @royalsociety and @RSocPublishing with #ScienceInTheMaking.