Louisiane Ferlier unveils the latest exhibition from the Royal Society Library, bringing back to life our 1923 summer soirée.

Much of the Royal Society’s work has gone on ‘behind the scenes’. In the early years, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, only Fellows and selected guests were invited to attend the weekly meetings, where experiments were conducted, and theories discussed. Then over time, as the institution grew, it became a hub for the administration, dissemination and funding of scientific research.

There have, however, also been notable exceptions when the Royal Society becomes a public place of science. Since the nineteenth century, in one form or another, there have been summer soirées when the Society hosts scientists showcasing their latest research, and opens its doors to a wider audience.

This week is the modern incarnation of this event: Summer Science 2023. Until Sunday, you can visit us at Carlton House Terrace to discover the work of research teams from across the UK. Alongside the main programme, the Library collections team also unveils a physical exhibition every year.

I am delighted to say that this time we’ve turned to the history of the soirées to bring back to life the programme showcased in 1923.

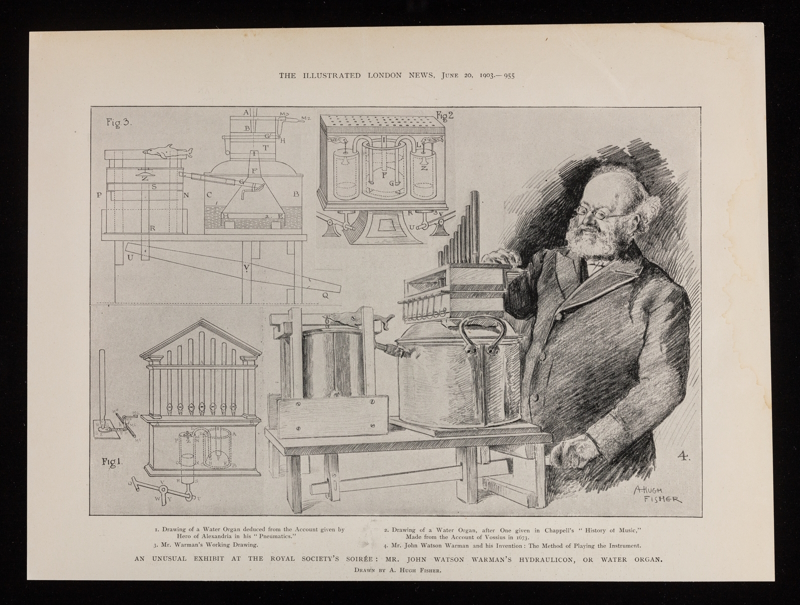

It’s been tremendous fun rediscovering what cutting-edge science was like 100 years ago. From telecommunications to plant genetics, science and technology were advancing rapidly in the 1920s. Looking at the list of the 50 exhibitors and demonstrations, I was struck by the large number of instrument-makers or technological companies demonstrating their latest inventions: a new magnetic alloy, the latest accessories for microscopes and measuring devices, a recently-invented high-speed camera capable of capturing up to 5,000 frames per second. There was even a stereoscopic projector (PDF) whose Romanian inventor, Demetrius Leonida Daponte, seems to have been rather lost to history.

Only one woman, Dorothy Cayley (above), presented her scientific work, indicating the terrible gender imbalance at the time. Cayley spent her whole career at the John Innes Horticultural Institution, which was set up in 1910 to conduct genetic research on plants. The work she presented at the 1923 soirées identified the genetic profile of a fungus responsible for die-back in fruit trees, but she is more famous for her later work on ‘breaking’ in tulips. In collaboration with the John Innes Centre, we’ve curated a full display dedicated to Dorothy Cayley, and along the way I’ve learnt a lot more about the crucial role played by women in early genetic research.

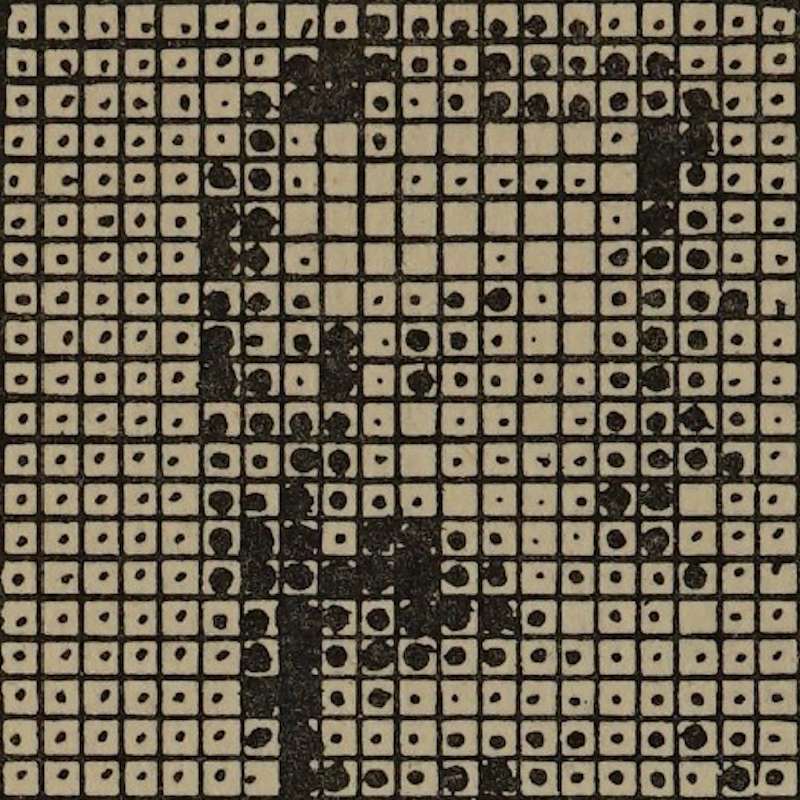

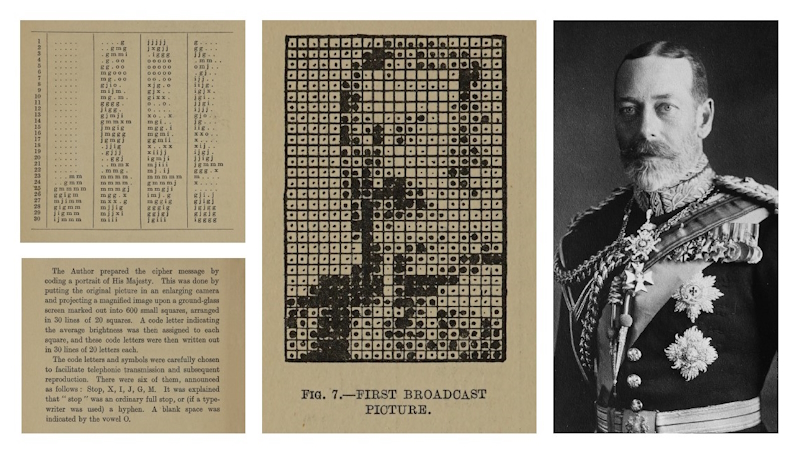

One of my other favourite exhibits captures the technological progress made in the 1920s, directly related to the creation of the BBC a few months earlier, marking the beginnings of radio broadcasting in the UK. Here, a physicist with a particular interest in acoustics, Edmund Fournier d’Albe, ‘broadcast’ a picture via radio waves, or wirelessly, for the first time ever.

Fournier d’Albe simply encoded a portrait of King George V, dividing the official photograph in areas of shading – a total of 600 dots. He read out the code and its cipher during the broadcast, reporting that 250 listeners were then able to receive the ‘image’ transmitted through the air.

Fournier d’Albe turns out to be a fascinating figure: a Celtic revivalist who lectured in Esperanto, he also invented a text-to-voice instrument designed to enable blind people to ‘read’ non-braille print. The ‘Optophone’ worked well but was seen as too costly to be commercialised. In his book dedicated to selenium, the photosensitive properties of which underpin the Optophone, d’Albe also predicted that wired or wireless television was around the corner. And indeed, the inventor of the first television transmission, John Logie Baird, started his work in the same year, 1923, en route to demonstrating the world’s first live working television in 1926.

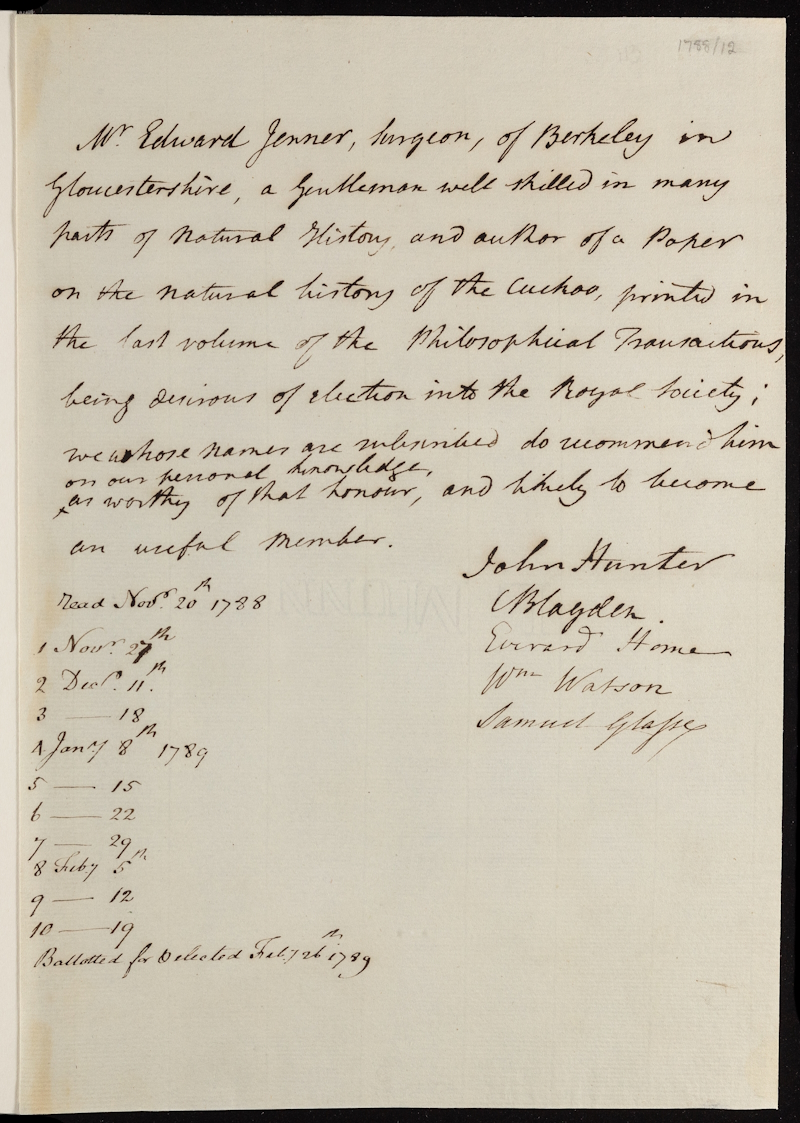

Alongside the latest discoveries, the 1923 soirée also looked back at earlier science, displaying copies of some very early Egyptian tools from the Science Museum and commemorating the centenary of the passing of smallpox vaccine creator Edward Jenner FRS (1749-1823).

Edward Jenner's Royal Society election certificate EC/1788/12

Edward Jenner's Royal Society election certificate EC/1788/12

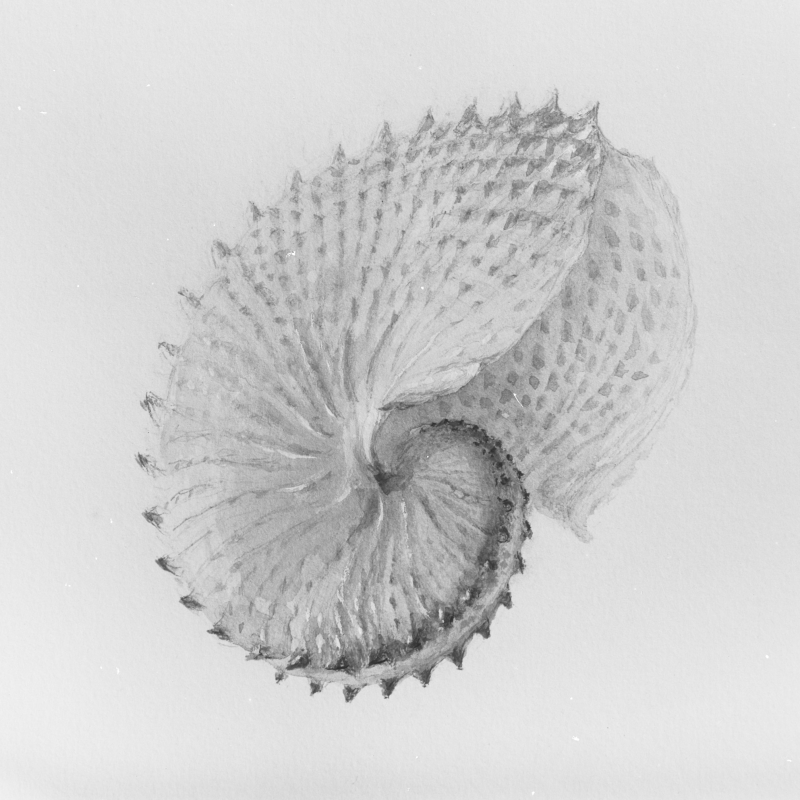

Overall, the 1923 exhibits reflected a fast-moving period for the scientific world, which was rebuilding itself after the First World War. From giant fossils to succulent plants, the soirées demonstrated not only the spectacular in the natural world, but the collaborative nature of science itself.

It’s been a pleasure, in turn, to collaborate with the Royal Microscopical Society, the John Innes Historical Collections, Kew Gardens and others to recreate the scientific exhibition displayed a century ago. I hope you’ll visit us to travel back in time and discover what science looked like in 1923.

While Summer Science may be finished by the end of this week, this Royal Society Library exhibition will remain open to the public until October, from 10am to 5pm on weekdays.