Jon Bushell looks at the career of A V Hill FRS, awarded the Nobel Prize for his work on heat in muscles, and a leading light in the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning during World War II.

The role of science and scientists during wartime is a common topic of interest for researchers, and the recent release of Oppenheimer has certainly cast additional light on the subject. You’ll spot a few Fellows of the Royal Society in the movie, including Patrick Blackett and Julius Robert Oppenheimer himself, elected as a Foreign Member in 1962.

As it happens, I’ve been looking at the archives of another of our Fellows, Archibald Vivian Hill (1886-1977), whose own work during the Second World War was fascinating. A V Hill, as he preferred to be known, studied mathematics at Cambridge. He put those skills to use during the First World War at the Munitions Inventions Department, where he was tasked with improving the precision of Britain’s anti-aircraft guns. His team of scientists, dubbed ‘Hill’s Brigands’, created accurate range tables for artillery and trained gunners in how to use them. In May 1918 Hill was elected to the Fellowship at the age of 31.

It wasn’t mathematics that ended up defining Hill’s scientific career. He grew bored with the subject at Cambridge and switched to a natural science course as the suggestion of Sir Walter Fletcher. Hill joined the Physiological Laboratory, focusing his post-WWI studies on the mechanics of muscles and investigating the heat they generate during contraction.

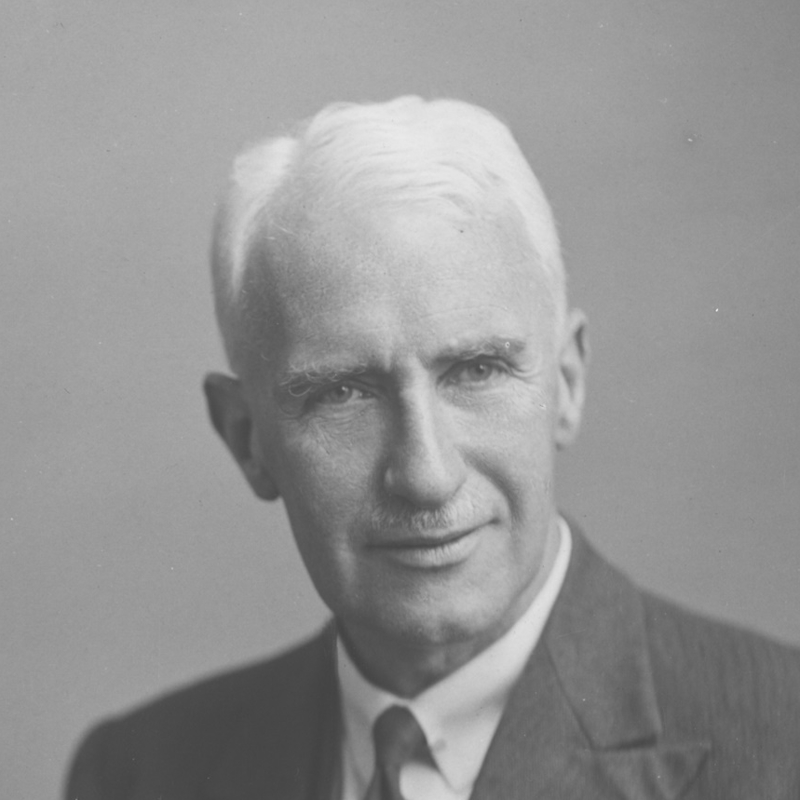

A V Hill and respiratory guinea-pig, 1928 (RS.18693)

A V Hill and respiratory guinea-pig, 1928 (RS.18693)

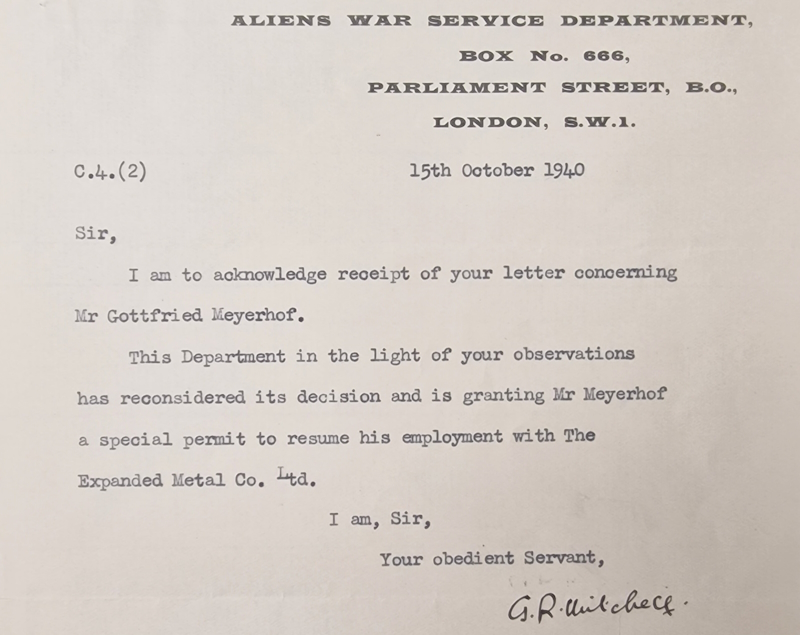

This brought him into contact with Otto Meyerhof at the University of Kiel in Germany, who was doing complementary research on lactic acid in muscle tissue. Their research led to the pair sharing the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and they became lifelong friends as a result. During the Second World War, Hill supported Otto’s son, Gottfried, in England. When Gottfried lost his job in 1940 because of his nationality, Hill was successful in petitioning to have him reinstated:

Letter to A V Hill from the Aliens War Service Department, 15 October 1940 (MDA/A/26/11/62)

Letter to A V Hill from the Aliens War Service Department, 15 October 1940 (MDA/A/26/11/62)

In 1923 Hill took up a post at University College London as professor of physiology, and in 1926 the Royal Society offered him a Foulerton Professorship which he held until 1951. In 1935 he became the Society’s Biological Secretary, a position he occupied until the end of the Second World War, followed by a further year as the Foreign Secretary from 1945 to 1946. Most of Hill’s records in our collections coincide with this Council service, when he played a crucial role in compiling the Central Register of Scientific and Technical Personnel, a directory of scientists to whom the British government could assign war-related research at the outbreak of hostilities in 1939.

Hill’s laboratory at UCL was shuttered when the War began. With his research on hold, Hill’s career took a political turn. At this time, Cambridge University had its own constituency and Member of Parliament. Hill stood and was elected in 1940. His position as an MP gave him a useful platform from which he could champion the cause of easing the plight of refugees from Europe, particularly refugee scientists.

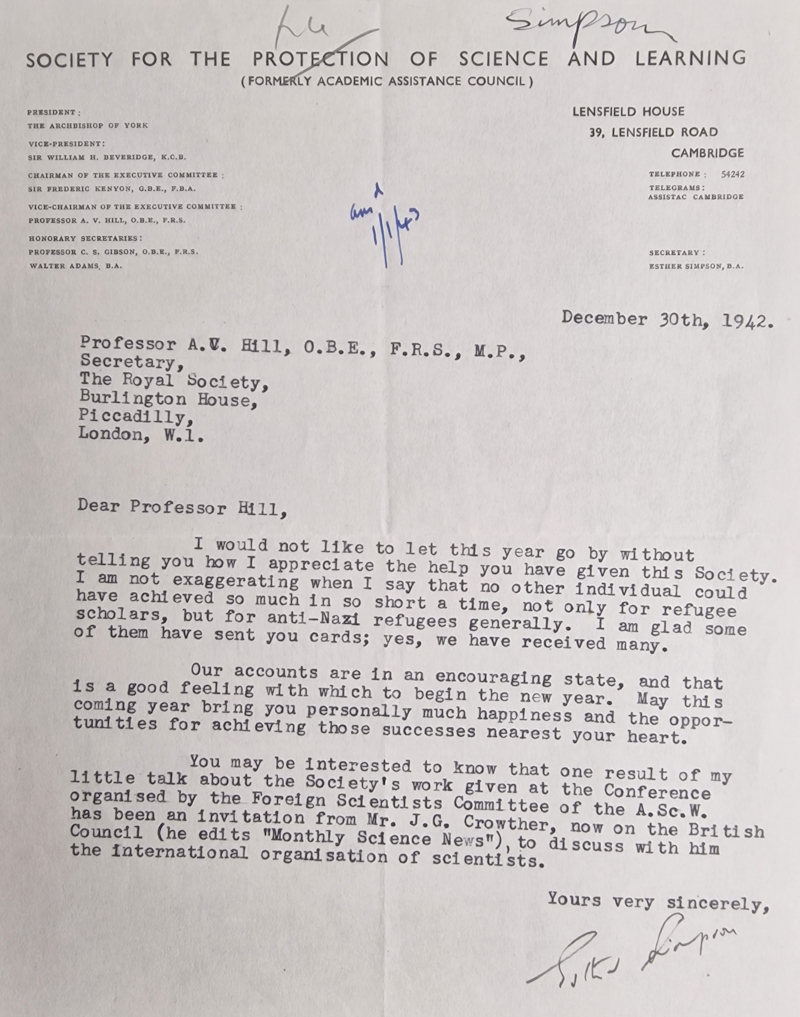

In 1933, Sir William Beveridge founded the Academic Assistance Council, to help German intellectuals, many of them Jews, dismissed based on ideological or racial grounds. He quickly recruited Hill as one of the organisation’s Council members. In 1936 the name changed to the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL – now CARA), which by the end of WWII had helped thousands of academics escape from Europe to the UK or the United States. The organisation also secured the release of many refugee scientists from Britain’s internment camps. I’ve covered the story of one interred refugee in an earlier blogpost.

Letter from Esther Simpson, secretary of the SPSL, thanking Hill for his work for the organisation, 30 December 1942 (from MDA/A/28/11)

Letter from Esther Simpson, secretary of the SPSL, thanking Hill for his work for the organisation, 30 December 1942 (from MDA/A/28/11)

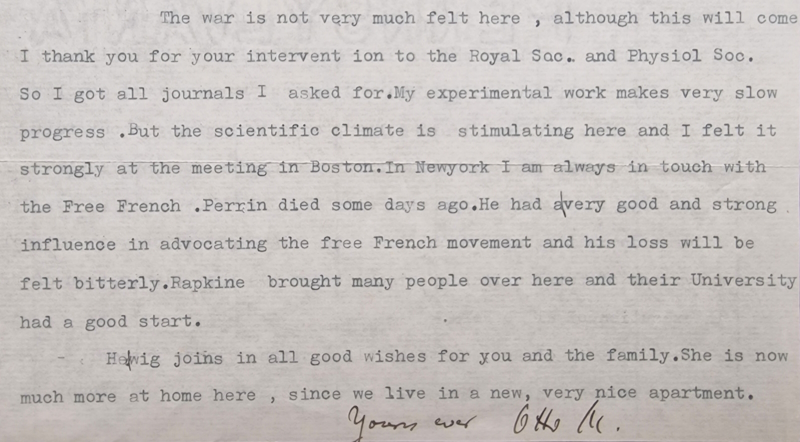

Hill played an active role in the SPSL throughout the war, alongside his other commitments. One scientist Hill was keen to help was his old friend Meyerhof. By 1930 Meyerhof held a prestigious position at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, a post he was determined to keep despite his Jewish heritage. He was finally expelled from his position in 1938 and fled with his family, initially to Paris, but when the Nazis took France in 1940 they were forced to move again.

By this time, it wasn’t possible for the SPSL to get the Meyerhofs to Britain. Instead, Hill was able to use his connections to help get them into the United States. Andrew Brown’s recent book, Bound by Muscle, covers the careers of both Hill and Meyerhof, and gives a detailed account of the Meyerhof family’s escape from Europe.

Extract of a letter from Meyerhof to Hill, discussing his situation in Philadelphia, 1942 (MDA/A/26/11/70)

Extract of a letter from Meyerhof to Hill, discussing his situation in Philadelphia, 1942 (MDA/A/26/11/70)

It’s fair to say Hill kept himself busy during WWII, but when hostilities came to an end, he was only too keen to stand down as an MP and return to UCL, where he spent the next several years rebuilding his laboratory.

Hill finally retired from his Foulerton Professorship in 1951, but not before convincing UCL to establish a new Biophysics Department. In fact, he continued his laboratory work at the University for the next two decades. Despite being well into his eighties by the end of the Sixties, he was anything but over the hill.

Top image: Portrait of A V Hill taken in 1942, copyright Godfrey Argent Studio