Jon Bushell looks at the Royal Society's portraits of Edmond Halley, and a diagram of Halley's curious model for the internal structure of the Earth.

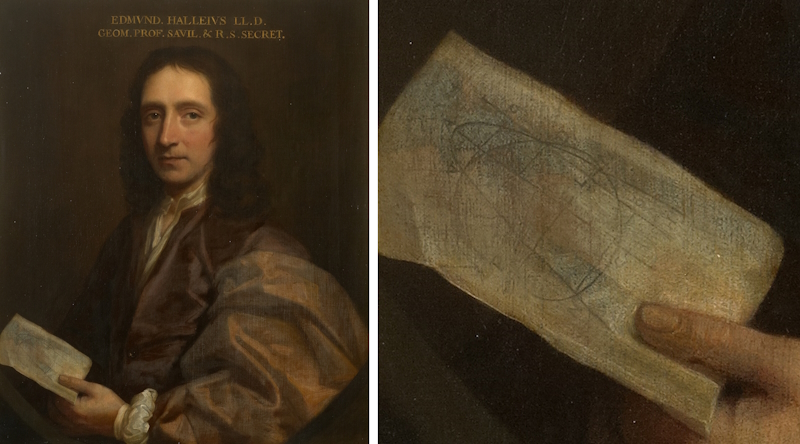

The Royal Society owns two portraits of Edmond Halley FRS. The first, painted by Thomas Murray, shows Halley in his mid-thirties and dates to around 1690, while our 1736 portrait by the Swedish artist Michael Dahl has a much older Halley during his time as Astronomer Royal.

RS.9284, with a close-up of the paper in Halley’s hand

RS.9284, with a close-up of the paper in Halley’s hand

In both paintings, Halley is posed holding a representation of his scientific work. The 1690 portrait (above) shows him with a diagram of an elliptical orbit, a reference to the astronomical research that had defined much of his early scientific career. A catalogue of stars he created while in Saint Helena had helped ensure his election to the Royal Society in 1678 at the age of 22. In 1682 he had made some observations of a comet, and by calculating the orbit he was able to predict its return in 1758. Halley didn’t live to see his theory play out, but ‘Halley’s Comet’ returned just as he had predicted.

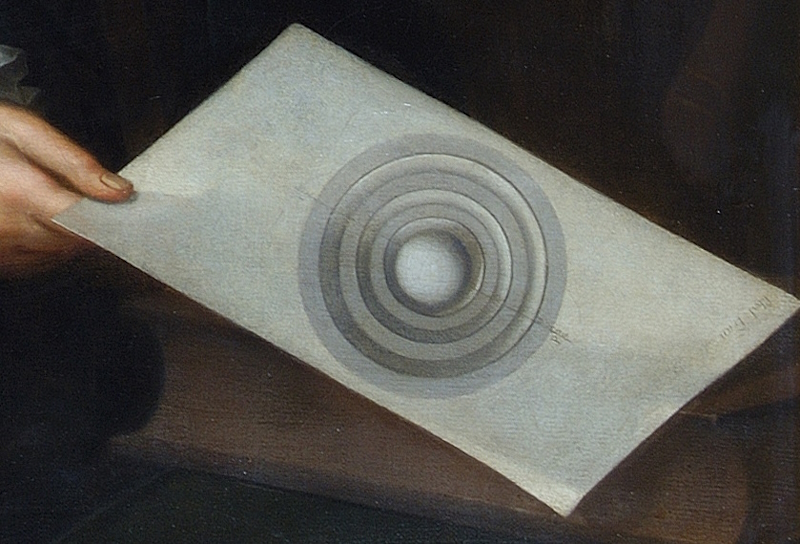

The 1736 painting (above) is perhaps the more interesting of the two, because the figure Halley is holding is not a reflection of his contemporary research agenda at all. Rather, it comes from a paper published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society back in 1692, under the pithy title of ‘An Account of the cause of the Change of the Variation of the Magnetical Needle. with an Hypothesis of the Structure of the Internal parts of the Earth’. This proposed a unique model for the internal structure of the Earth, to explain why magnetic north was not fixed. The diagram of a sphere, surrounded by three thick concentric circles, represents Halley’s supposed planetary interior, inspired by Saturn’s rings.

Close-up of the figure held by Halley in the 1736 portrait

Close-up of the figure held by Halley in the 1736 portrait

Geomagnetism was a significant area of research throughout Halley’s career. He published on the subject in the Philosophical Transactions as early as 1683. The ‘deflection of the Magnetical Needle from the true Meridian’ was of particular interest to Halley, who believed it held the key to solving one of the greatest challenges of the age: how to determine longitude at sea. He later undertook two Atlantic voyages in 1698 and 1699 to measure magnetic declination, and published one of the first isogonic maps as a result. But gathering data was one thing, and explaining it was quite another. Halley conceived his model of the Earth to do just that.

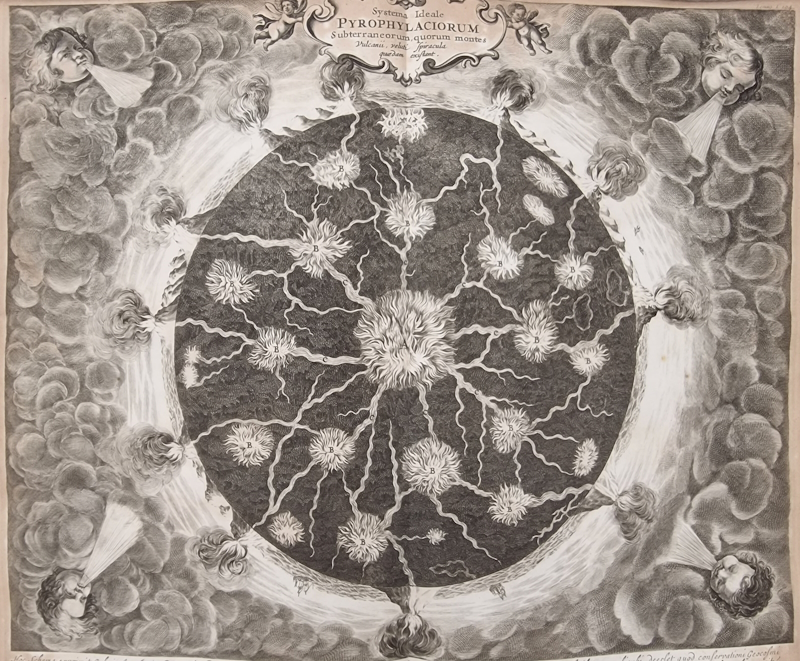

By the seventeenth century, the Earth was understood to be one giant magnet, thanks to William Gilbert’s experiments with terrellae and his publication of De Magnete in 1600. Gilbert suggested that the presence of iron inside the planet might be generating the magnetic field, but beyond this the structure of the interior was a mystery. The German scholar Athanasius Kircher presented one possible model in Mundus Subterraneus in 1664, based on his research on the crater of Vesuvius. He depicted the Earth with a huge ball of fire at its centre, with various channels and underground chambers leading up to volcanoes on the surface:

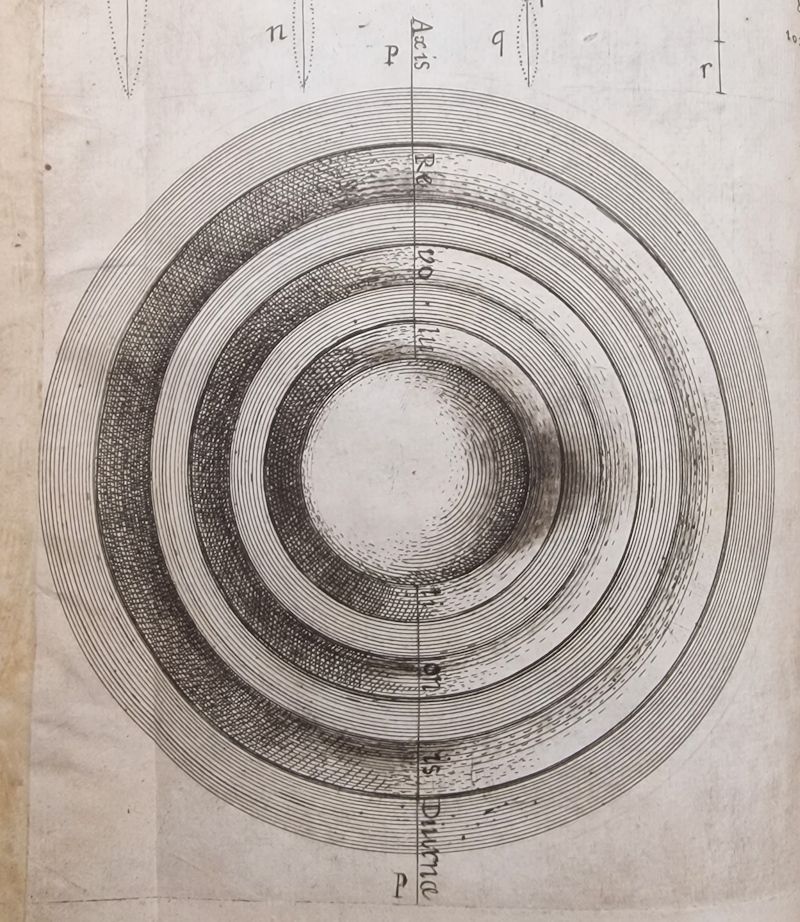

As we’ve seen, Halley’s model of the Earth’s interior takes the form of a series of hollow spheres around a central core. His argument was that the exterior of the Earth has its own magnetic north and south pole, but that there must be four poles in total. At the centre of his hollow Earth is a core which Halley argued would have its own north and south poles. If that core rotated at a different speed to the exterior, then the interactions between poles would give rise to the changes in magnetic declination observed with a compass. In positing the existence of a central core, Halley was touching upon the truth long before anyone could prove it – the Earth’s core wasn’t conclusively evidenced until 1906, based on measurements of earthquake shockwaves made by Richard Oldham FRS.

Halley read an early version of his paper at a meeting of the Royal Society on 25 November 1691, and presented the figure at the next meeting. A longer version of the essay was then read and ordered for printing in the Transactions at the meeting on 27 January 1692.

Halley’s Earth diagram as it appeared in the Philosophical Transactions

Halley’s Earth diagram as it appeared in the Philosophical Transactions

Astute readers may have noted that Halley explained the magnetic variations with reference to the surface and the core. So why does his figure include multiple layers in between? At this time, it was believed that all the planets must be capable of supporting life, and Halley argued that putting more creations inside the Earth was simply an efficient use of space for an almighty God: ‘We ourselves, in Cities where we are pressed for room, commonly build many Stories one over the other, and thereby accommodate a much greater multitude of Inhabitants’. As for light, he proposed that the very air could be luminous, or that the underside of each shell might shine like the sun.

Halley closed his paper by saying that ‘If this Short Essay shall find a kind acceptance, I shall be encouraged to enquire farther’. Given that he never returned to the subject, it’s fair to speculate he wasn’t thrilled by its reception. Patricia Fara has suggested that this paper was part of Halley’s attempt to boost his religious credentials while (unsuccessfully) applying for a post at Oxford University.

Nevertheless, its inclusion in the portrait many years later hints at Halley’s confidence in his model. No doubt he was hoping that time would prove him right, but it was not to be. The 1774 Schiehallion experiment, which determined the planet’s density, conclusively disproved any hollow Earth theory. Given his extensive body of work, it’s a bit unfortunate that Halley chose to have one of his less successful speculations immortalised on canvas. I’m sure Jules Verne would have approved, however.