Large numbers of people who have been infected by the virus that causes Covid-19 are experiencing symptoms months and even years later. Charles Bangham, Professor of Immunology at Imperial College London, examines just what we now know about Long Covid and whether there is hope for those that suffer with it.

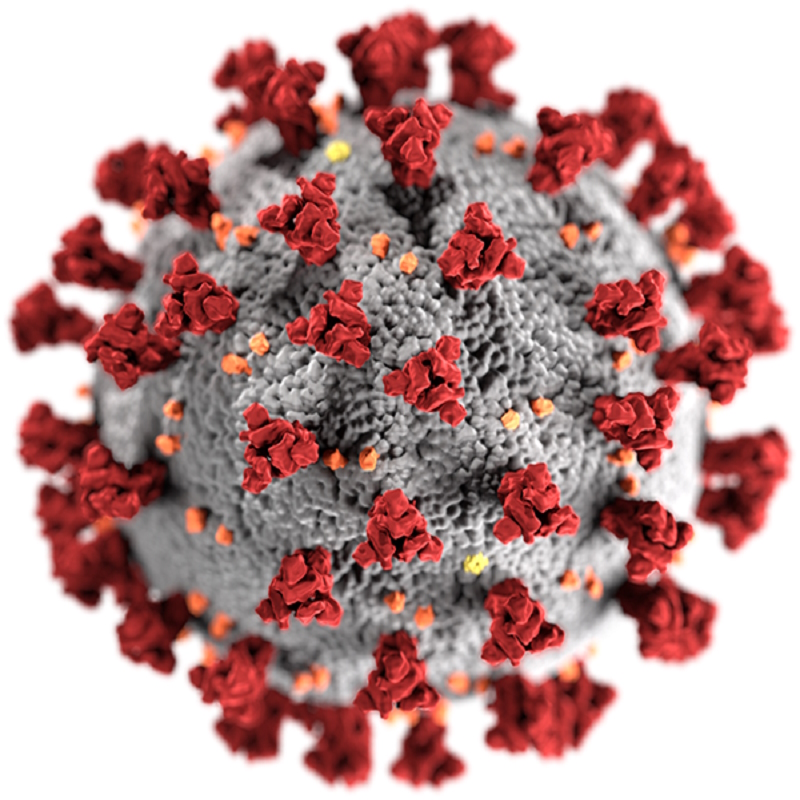

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, a perplexing and often debilitating condition has shadowed coronavirus infections. While some people get no symptoms at all, and most recover completely, around one in eight people who test positive for SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for Covid-19, go on to experience a constellation of chronic symptoms that appear weeks, months and even years later.

Long Covid – as this condition is now widely known – has remained as one of the enduring puzzles of the pandemic, even as our knowledge of the virus itself has improved. Virologists, clinicians and patients are still wrestling with understanding what causes Long Covid, how to treat it and the recovery process involved.

There are even still several definitions of exactly what Long Covid is. The World Health Organization’s Delphi Consensus, for example, describes “post-Covid-19 condition” as being symptoms that cannot otherwise be explained and occur usually within three months of the onset of Covid-19, lasting for at least two months. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), by comparison, defines Long Covid as a “multi-system condition” with symptoms that continue for more than four weeks. It adds that Long Covid may consist of “a number of distinct syndromes” including post-viral fatigue syndrome, post-ICU syndrome, long-term Covid syndrome, and permanent organ damage.

The picture is far from clear, partly because the symptoms can be so diverse. The most common symptom by a considerable margin is ongoing and intermittent fatigue, along with “brain fog”, memory problems or confusion. But there are at least 37 symptoms that have been identified as frequently occurring in Long Covid patients, and as many as 200 other symptoms in 10 different organ systems have been described in some people with the condition.

This makes diagnosing Long Covid a difficult process, even with the definitions above – no diagnostic test yet exists. There is some indication that medical sniffer dogs may be able to identify Long Covid from volatile biochemicals in sweat samples, although it is still too early to say if this could be used more widely.

But there are some clues emerging about what the underlying cause of Long Covid might be, how patients can manage it and even some signs of hope for what the future might hold. As a virologist, to me perhaps the most difficult but fascinating aspect is how this long-term illness is being caused in the first place. You need to have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 to trigger it, but that is where the certainty ends.

There are a number of theories about what might be going on inside the body both during and after infection with SARS-CoV-2 that might lead to the chronic symptoms patients are experiencing. For example, it has been suggested that a Covid-19 infection might trigger an autoimmune response, where the body’s immune system attacks its own tissues – but so far there is no convincing evidence for this. Other suggestions include tissue damage due to chronic inflammation or damage caused during the acute phase of the infection. A curious and unexplained finding is that people with Long Covid often have high levels of antibodies to other latent viruses in the body, in particular the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a known cause of post-viral fatigue syndrome, and varicella-zoster virus (VZV), the agent that causes chickenpox and shingles. But whether this reactivation is a cause or effect of Long Covid isn’t yet known.

The most recent research, however, appears to favour the idea that patients may fail to eradicate all traces of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from their bodies after an infection. Post-mortem studies of people who have died from Covid-19 indicate that RNA from the virus can be found in many different organs, including the nervous system and the brain. Protein or RNA has also been found lingering in the gut tissue, stool samples and blood of patients many months after they have otherwise recovered from the acute infection. People with Long Covid also tend to have persistently high immune responses against SARS-CoV-2, such as higher numbers of B-lymphocytes – the cells in the immune system that produce antibodies – and more antibody against the spike protein of the virus. This is consistent with the view that viral protein is persisting in the body somewhere.

There are also a number of other immunological abnormalities associated with Long Covid, but perhaps the most striking is that people with Long Covid appear to have lower concentrations of the steroid hormone cortisol in their blood. This “stress hormone” has an anti-inflammatory effect in the body – and steroid treatment was found to be one of the most effective ways to treat severe Covid in the acute phase of the disease.

Putting these things together, it looks as though some people fail to clear the virus from their body – perhaps because they have a less efficient immune response to it in the early phase of infection – allowing it to spread to other parts of the body. Although they manage to clear the virus from their respiratory system, the virus, or fragments of it – such as the viral RNA or proteins – persist in other organs and tissues. This in turn could lead to an ongoing inflammatory response.

An exciting new finding suggests how such an inflammatory response is caused. The coronavirus seems to trigger a chronic inflammation in the lining of blood vessels, which can lead to microclotting and impaired blood flow in small arteries. This inflammation may be perpetuated by a vicious circle: damage to a blood-vessel wall causes inflammation, which in turn causes more damage. This mechanism could explain why so many different organs can be affected - because of course all organs and tissues are supplied by small arteries.

There are still big questions about why some people seem to be unable to clear the virus, but as research continues, these mechanisms will hopefully become clearer.

In the meantime, treating Long Covid also remains a frustrating process. Without a clear indication of the underlying cause, clinicians have had to focus on treating specific symptoms. Some patients who experience the dizzy spells associated with Long Covid, for example, can find relief by taking beta-blockers.

There are some clues that antiviral drugs might help to prevent and even treat the condition, and clinical trials of these are already underway. Vaccines against Covid-19 have also been shown to offer some protection against the development of Long Covid, although the benefits of vaccination as a potential treatment for the chronic condition are much less clear. Some Long Covid sufferers have found doing limited, progressive physical exercise to be beneficial and it is being used by some clinics as a tool for managing a patient’s recovery. In some cases, however, pushing too hard can actually set people back. And it may be that rest is simply the best medicine in these cases.

We have come a long way since the uncertain days at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. In May 2023, the World Health Organization declared SARS-CoV-2 was now so well established around the world that it no longer fitted the definition to be classed as a global health emergency. But the WHO also points out that the pandemic is also far from over and SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve, with new variants leading to fresh waves of infections. The virus still claims lives, although many times fewer than earlier in the pandemic.

There is some evidence that the risk of developing Long Covid is lower with later variants, such as Omicron. It is estimated that at least 65 million people around the world have experienced Long Covid – but the real number may be much greater, and is growing all the time.

Can we predict who will develop Long Covid? The recent study mentioned above found that four factors in combination could predict the condition with over 80% accuracy: age, body mass index, and two protein complexes that are involved in inflammation. It will be exciting to see if these findings are reproduced in other studies – if so, then there should be hope for improvements in prevention and treatment of this distressing condition.

And as emerging variants trigger new outbreaks of Covid-19 in the future, in their wake Long Covid will continue to cast its shadow.