Rose Teanby looks at letters in the Royal Society archives highlighting Sir John Herschel’s influence on Anna Atkins, Julia Margaret Cameron and Mary Somerville.

Last week the Royal Society launched online access to the letters of Sir John Frederick William Herschel. Although women weren’t admitted as Fellows of the Royal Society until 1945, Herschel engaged in enthusiastic correspondence with women of science, encouraging their experimental endeavours. In this article I focus on his correspondence with three women: Anna Atkins, Julia Margaret Cameron and Mary Somerville.

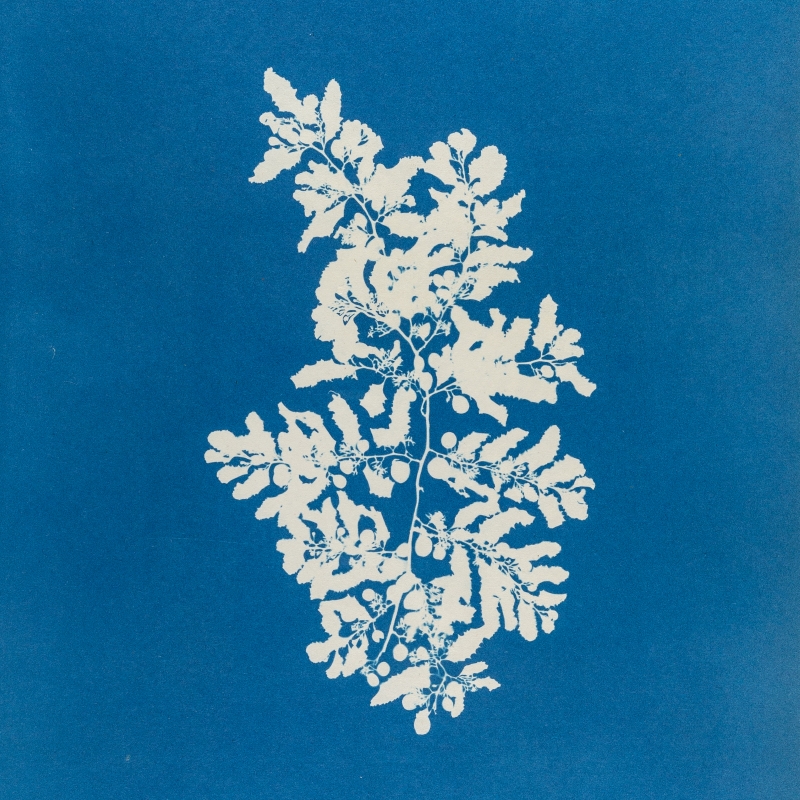

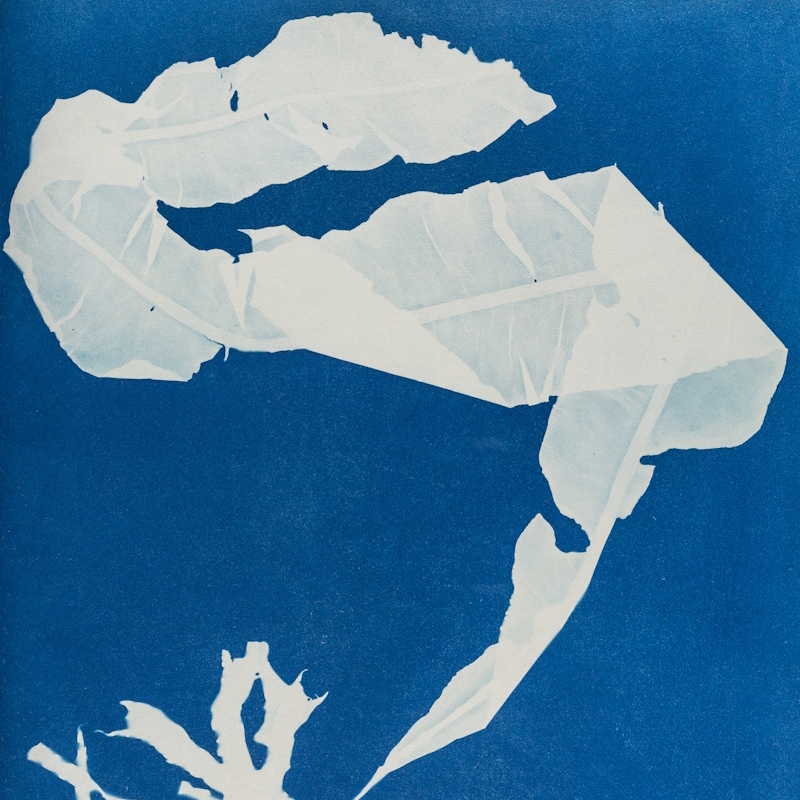

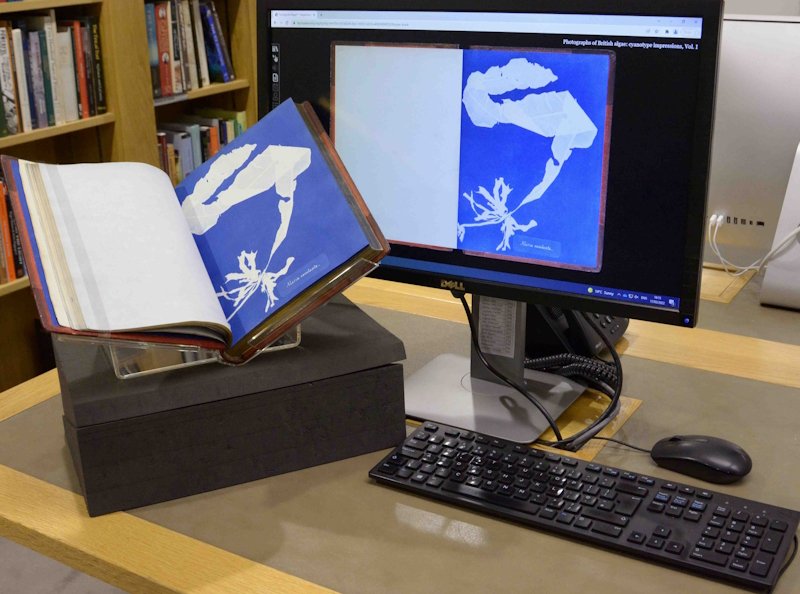

Herschel’s photographic discoveries included the cyanotype ‘blueprint’ process in 1842, a method adopted by botanist and pioneering photographer Anna Atkins. She embarked on a ten-year project to photograph approximately 400 specimens of British algae as an accompaniment to William Henry Harvey’s 1841 unillustrated A manual of the British algae. Her Photographs of British algae: cyanotype impressions is recognised as the first photographically produced book.

Anna Atkins acknowledged Herschel in her introduction:

‘The difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects as minute as many of the Algae and Confervae, has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of Cyanotype…’

Unfortunately there are no letters between Atkins and Herschel at the Royal Society, but her adoption of cyanotype photography is referenced in an 1844 letter from photographic pioneer Robert Hunt FRS to Herschel:

‘I have recently had some very friendly letters from Mr Children whose daughter Mrs Atkins is engaged in copying the Algae by your Cyanotype process – the effect is exceedingly pleasing.’

Perhaps Hunt had seen the first part of Photographs of British algae: cyanotype impressions, gifted to the Royal Society from ‘Mrs Atkins’ in October 1843. Hunt was well placed to assess Atkins’s cyanotype impressions, having experimented with the process himself. Hunt’s results were detailed in an 1842 letter to Herschel, lamenting his poor results due to the strength of the sun.

In the online Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot, Atkins is referenced in an 1864 published letter from Talbot to the editor of the British Journal of Photography:

‘... the cyanotype of Sir J. Herschel, by which process a lady, some years ago, photographed the entire series of British sea-weeds’.

Anna Atkins may be absent from Herschel’s correspondence, but thanks to the letters of her contemporaries she leaves an enigmatic trace of groundbreaking photography. Volume one of Photographs of British algae is available on Turning the Pages.

Anna Atkins Photographs of British algae: cyanotype impressions – volume one, original and digital image (photo R Teanby)

Anna Atkins Photographs of British algae: cyanotype impressions – volume one, original and digital image (photo R Teanby)

Herschel also maintained a long friendship with photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, their correspondence dating back to 1847 in the Royal Society’s collection. Her language was as emotive as her unique portraiture, as in this 1870 letter:

‘It lifted up my heart and seemed to fill up a yawning chasm when I got your ... letter.’

One 1858 letter poses further questions:

‘My Dear Sir John Herschel

I send you as my Xmas gift a photograph likeness most faithful & to all eyes most beautiful of your little god child with his three beloved sponsors to guide and guard him ever.

I don’t know whether this cherished group will ever meet all together in this world again as we met around the holy font on 25th February 1852 ...’

Where is that photograph and who was the photographer?

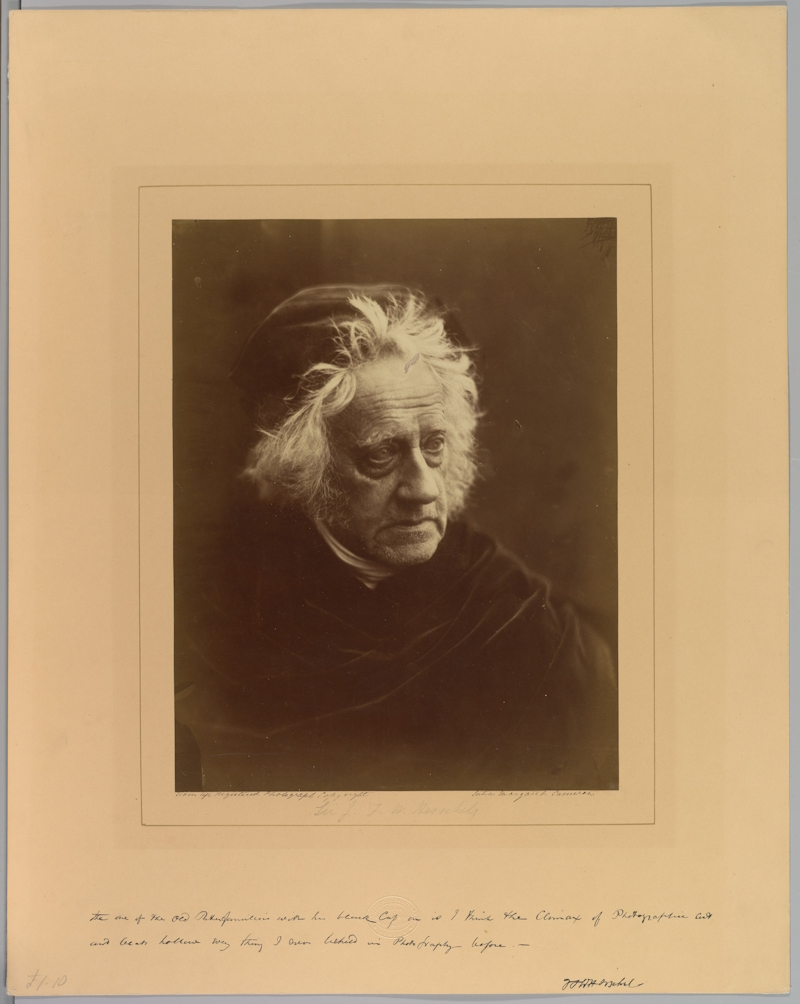

In 1867 Cameron photographed Herschel, describing the sitting in her memoir as ‘the high task of giving his portrait to the nation’. An interesting exchange between Herschel and James Samuelson highlights that he was ‘bound by promise to J. M. Cameron not to sit for other photographers’. This 1867 portrait mount includes the words:

‘The one of the old paterfamilias with his black cap on is I think the climax of photographic art and beats hollow every thing I ever beheld in photography before.’

John Frederick William Herschel by Julia Margaret Cameron, April 1867 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

John Frederick William Herschel by Julia Margaret Cameron, April 1867 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Herschel’s long relationship with the scientist and writer Mary Somerville incorporated photographic guidance for her study of scientific developments, On the connexion of the physical sciences. An 1843 letter from Somerville asked for his help in obtaining an account of the Daguerreotype process. In 1844 he responded:

‘… I have been awaiting some opportunity of conveying to your hands those papers of mine about Photography…’

The letter contained a feast of photographic instruction including practical directions for taking cyanotypes. These photographic processes were then included in On the connexions of the physical sciences. In September 1844 Somerville thanked him for his kindness:

‘I have now got photographic apparatus and books sufficient to keep me busy for a very long time and to you I owe that pleasure.’

Further writings between them evolved into her second Royal Society paper ‘On the action of the rays of the spectrum on vegetable juices’. Herschel’s support is clear in correspondence with Spencer Compton, Earl of Northampton FRS:

‘Perhaps as a Lady’s paper it might be placed on the secretary’s list for early reading and may be introduced as an ‘extract from a letter’ to myself and communicated by me.’

Mary Somerville’s correspondence with Herschel extended beyond scientific discussion, and in her memoir she described him as:

‘a dear and affectionate friend, whose advice was invaluable, and his society a charm.’

Mary Somerville, self-portrait. Somerville College, University of Oxford, by kind permission of the Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

Mary Somerville, self-portrait. Somerville College, University of Oxford, by kind permission of the Principal and Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

The letters to and from Sir John Herschel give valuable insights into his encouragement of women’s contributions to nineteenth-century scientific society. The innovative publications by Anna Atkins and Mary Somerville are still in the Royal Society Library, and Julia Margaret Cameron’s ’paterfamilias’ portrait now forms part of a legendary portfolio of images created ahead of their time.

In an era when women were still marginalised from institutional science, these letters show that Mrs Atkins, Mrs Cameron and Mrs Somerville were given the precious gift of equal opportunity thanks to Sir John Herschel.