Ainsley Vinall discovers how past Fellows of the Royal Society have spent their summer holidays.

It’s finally starting to feel like summer at the Royal Society, with our highly anticipated Summer Science Exhibition opening next week. As we edge ever closer to the summer holidays, I’ve been researching how past Fellows of the Royal Society unwound on their holidays. Although we have innumerable records of lengthy voyages and intrepid expeditions in our archives, I’m also interested in what Fellows got up to if they could only have a few weeks away from their work.

One of our earliest records of a holiday trip is in an extract of a letter (MS/249 item 87) that the young Christopher Wren (1632-1723) wrote to his father in 1649, eleven years before he became a Founder Fellow of the Royal Society. Written in Latin, the letter details his trip visiting some friends in Cornwall (Cornicum Respublica). Enjoying the natural landscapes, he declared the sand, valleys and grass of the Cornish countryside to be an earthly paradise (paradisum esse terrestrem).

After the Royal Society was established, holidays were made possible in the early days by an annual recess over the summer months when there were no meetings of the Fellows. Not one to allow a holiday to distract him from natural philosophical endeavours, Denis Papin FRS (1647-1713) used his summer break in 1684 to conduct a series of experiments which he recorded for the Society. These included air pump observations ‘on a frog, & a fly […] warm water, cold water, warm beer in vacuo’ as well as buoyancy tests ‘with a cork in water’.

The mathematician and father of computing Charles Babbage FRS (1791-1871) preferred a city break to a sojourn in the countryside it seems, and used his mathematical expertise to help plan his holidays. In a letter from 1823 to his frequent travelling companion Sir John Herschel FRS (1792-1871), he explained ‘at present we think of going direct to Birmingham thence to Manchester and thence by some yet undiscovered curve whose coordinates are junctions of pure chance to places as yet unknown […] if you can join us for the whole or any portion of our tour it will render it so much the more pleasant’.

Not every aspect of the holidays recorded in our archives went to plan. In 1846 the boat carrying George Biddell Airy FRS (1801-1892) and his family back home from a trip to Germany was caught in rough waters. His wife Richarda Airy (1804-1875) described how the whole family ‘were tossing about, holding ourselves into our berths as well as we could to save ourselves from being hurled out onto the cabin floor, ignorant of what or how much danger there might be, yet knowing that there was some, and terrified by the strange noises overhead’. The family made it back home safe and sound, but Ricarda described how the frightening return voyage had ‘almost driven the pleasures of our delightful journey out of our heads’.

A much more relaxing sojourn was had by John Forbes FRS (1787-1861), physician to Queen Victoria, and recounted in his 1848 book A physician's holiday; or, A month in Switzerland. In the introduction Forbes extolled the medical benefits of a summer break, explaining that ‘a travelling trip to Wales, to Scotland, or to the continent, is one of the commonest forms of holiday-making for the London physician […] he returns to his home a new man, sunburnt and buoyant and keener and defter in his vocation than ever.’

Forbes’s walking tour around Switzerland, viewing the Rhine Falls by moonlight and observing the Matterhorn peeking through the clouds at sunrise, sounds delightful. He noted that some may find the constant walking tough, but even had a solution to that, recommending that walkers ‘support their strength with a moderate use of wine or spirits’.

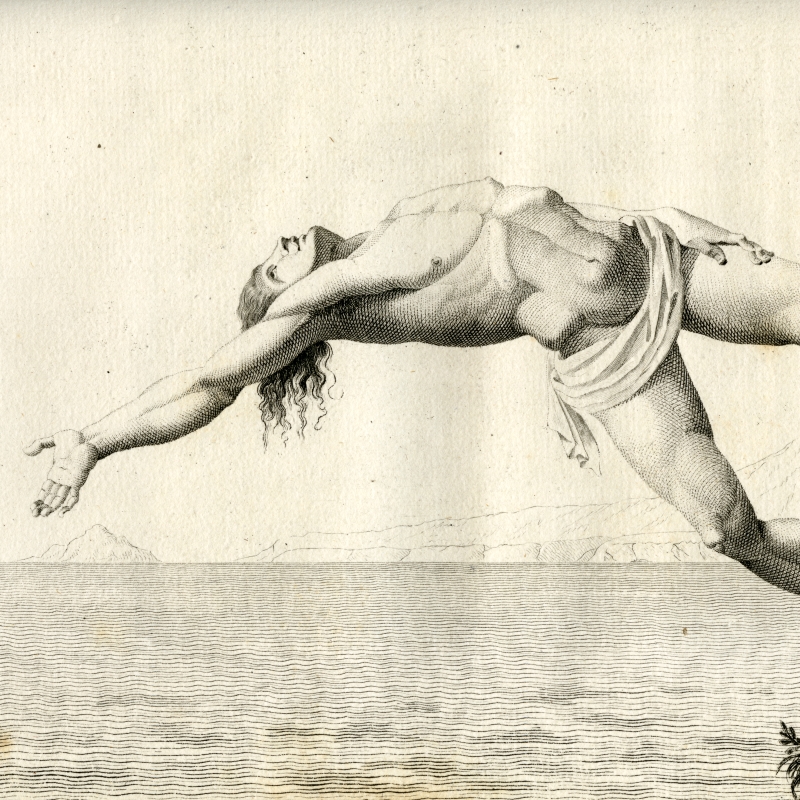

One of our most adventurous holidaymaking Fellows was Irish physicist John Tyndall FRS (1820-1893), who published an account of one of his trips as Mountaineering in 1861: a vacation tour. However, this title is deceptive – the book is no light-hearted retelling of a bit of scrambling in the hills, but a record of the gruelling first ascent of the Weisshorn, a 4,500m peak previously deemed unclimbable.

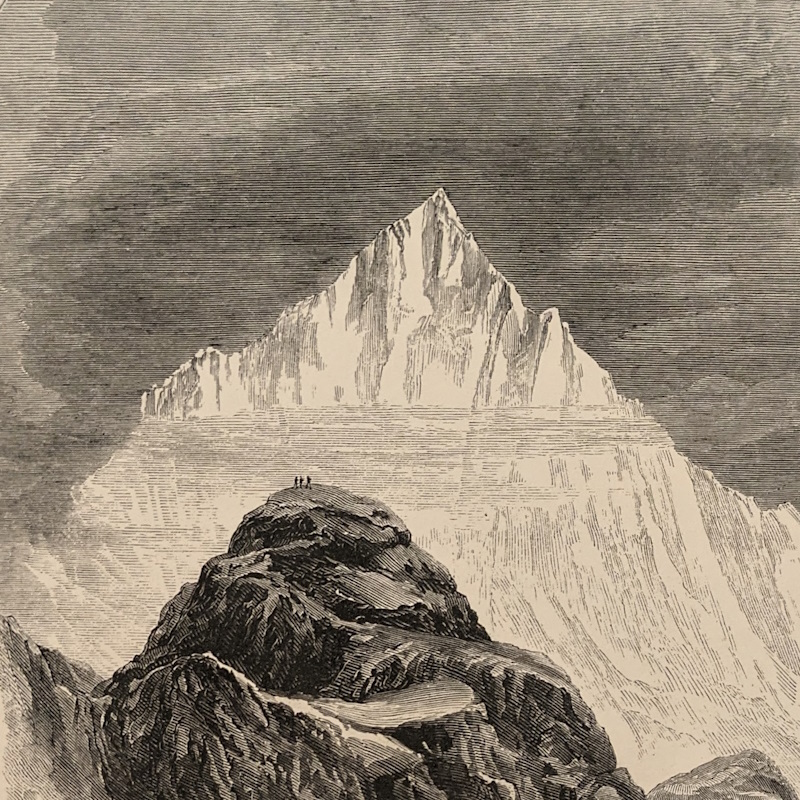

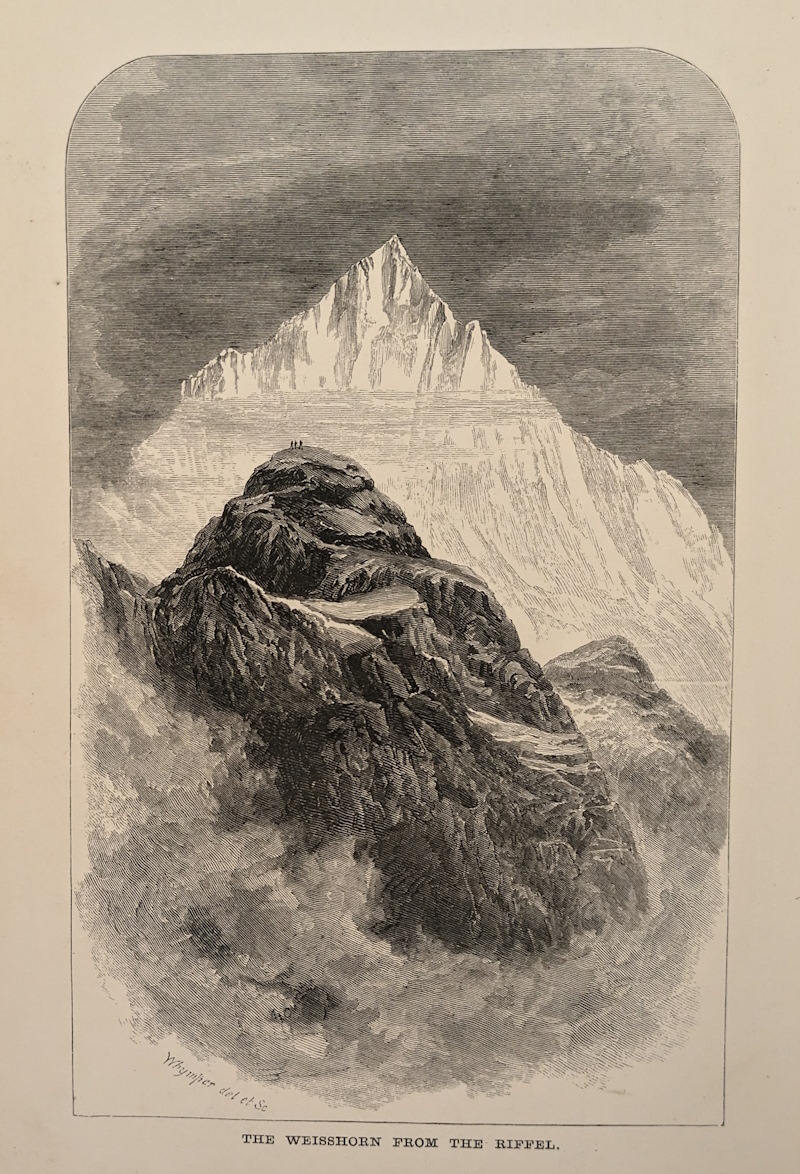

View of the Weisshorn from John Tyndall’s Mountaineering in 1861

View of the Weisshorn from John Tyndall’s Mountaineering in 1861

Tyndall and his two guides, J J Bennen and Ulrich Wenger, rappelled past rocky towers and traversed knife-sharp ridges to become the first alpinists to reach the summit, where they planted a small makeshift flag. Maintaining their strength in a way John Forbes would surely approve of, Tyndall noted that the group carried ‘a bottle of champagne, which poured sparingly into our goblets on a little snow, furnishes Wenger and myself with many a refreshing draught.’

Tyndall first came to the Alps in 1856 for his scientific research into glacial motion, but regularly returned for leisure. He became one of the foremost alpinists of his day and saw inherent links between mountain climbing and physics. In his book, he described how observing one of his guides compressing snow to see if it was firm enough to cross brought to his mind ‘the simple observation made by Faraday, […] when pressed, the attachments of its granules were innumerable, and their perfect cleanness enabled them to freeze together with a maximum energy.’

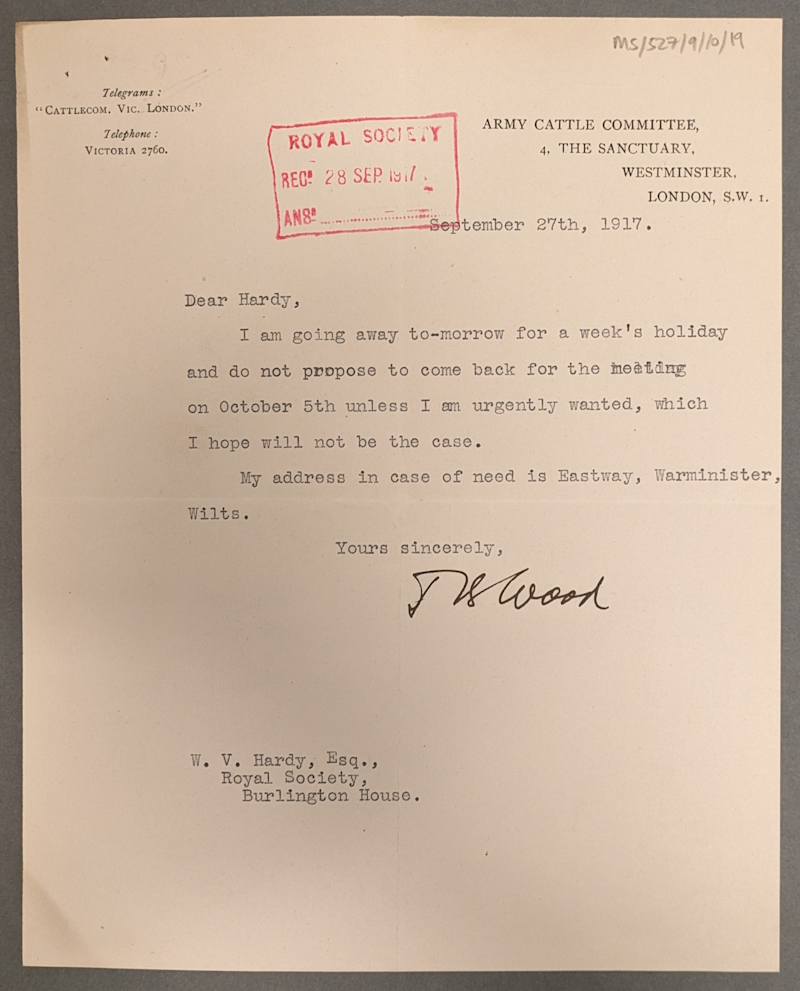

Whether conducting experiments, sipping champagne on a mountain or walking through the countryside, it’s important to switch off from work when on a summer break. Perhaps we can all take inspiration from this 1917 letter to biologist William Bate Hardy FRS (1864-1934) from T S Wood, one of his colleagues, whose ‘out of office’ states: ‘I am going away to-morrow for a week’s holiday and do not propose to come back for the meeting on October 5th unless I am urgently wanted, which I hope will not be the case.’

Note from T S Wood to William Bate Hardy, 27 September 1917 (MS/527/9/10/19)

Note from T S Wood to William Bate Hardy, 27 September 1917 (MS/527/9/10/19)

Whatever your plans are this summer – and I hope they include a visit to our Summer Science Exhibition next week – it’s important to remember that even the greatest minds need a break every now and then.