Katherine Marshall discovers a beautiful seventeenth-century treatise on petrified wood in the collections of the Royal Society Library.

A hidden gem in the Royal Society Library is a treatise on petrified wood by Francesco Stelluti (1577-1652).

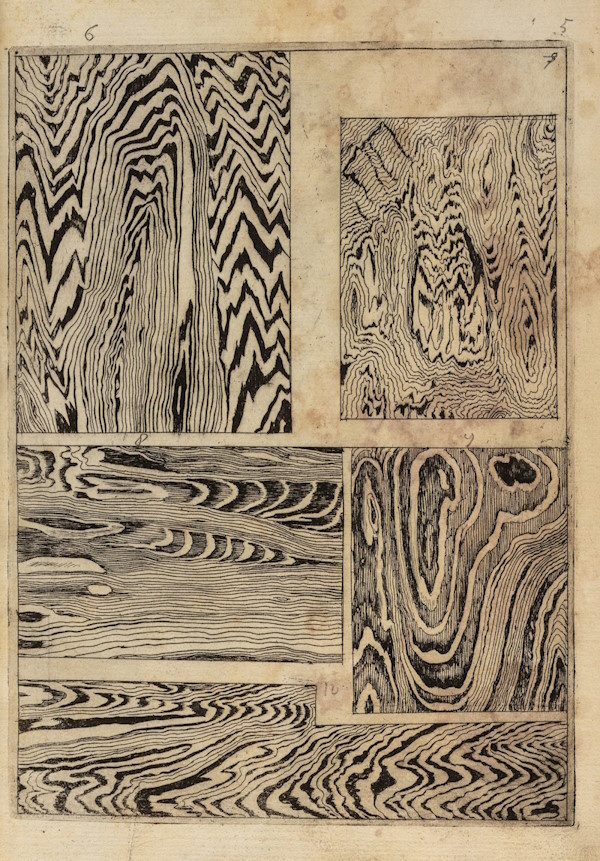

Looking for resources to digitise for our Picture Library, I was drawn to Stelluti’s Trattato del legno fossile minerale nuovamente scoperto (‘Treatise of the newly discovered fossil mineral wood’), published in Rome in 1637, because of the close-up illustrations of wood veining or ‘wave patterns’. Stelluti included 16 of these figures to show not only the variety of the waves and how they differ from conventional wood markings but also their beauty, as striking example of art forms in nature.

Wave patterns in fossilised wood: plate 5 of Stelluti’s Trattato (RS.21722)

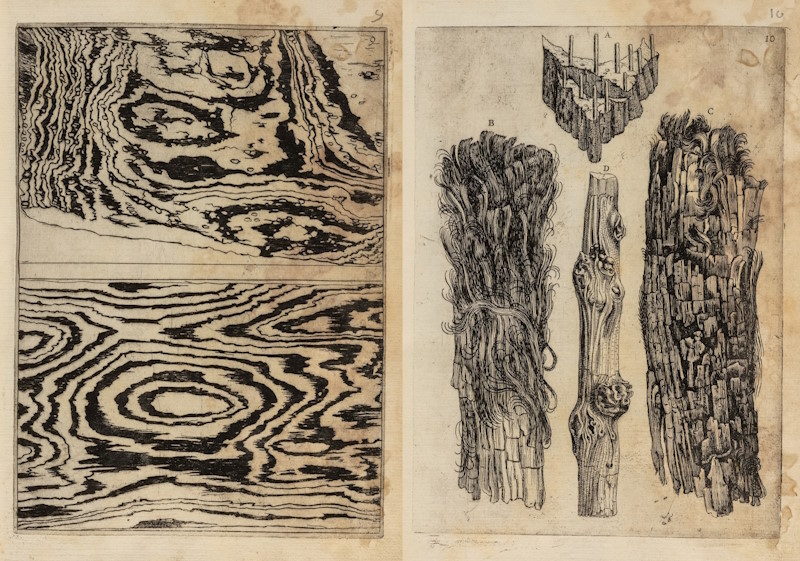

The investigation into the fossil wood of Umbria, Italy, was initially the work of Prince Federico Cesi, founder and patron of the Accademia dei Lincei. Stelluti, also a founder member, continued the project after Cesi’s death in 1630, and published their findings seven years later. He argued that the subterranean wood was a ‘metallophyte’, a type of hybrid between wood and metal, though much closer to plants in nature. In the illustrations below, plate 9 (left) shows small pieces of metal within a specimen, represented as small circles; a further example in plate 10 (right), labelled ‘A’, shows a piece of spice wood with ‘rods’ of metal running through its length.

Fossilised wood with metal: plates 9 and 10 of Stelluti’s Trattato (RS.21726 and RS.21727)

The Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynxes) is considered the world’s first scientific academy. A figure of their symbolic lynx can be seen on the title page of Stelluti’s treatise, representing the keen eyesight needed to discover truth through observation. This new philosophy of the early scientific academy brings to mind the Society’s motto Nullius in verba: take nobody’s word for it, and verify truth through an appeal to facts determined by experiment.

Detail from the title page of Stelluti’s Trattato

Debates into the nature of fossilised material were prominent in the seventeenth century. Stelluti’s book found its way to the Royal Society via the writer and alchemist Thomas Henshaw FRS, who had translated a copy given to him by Sir Robert Paston FRS and read his translation at a meeting of the Royal Society on 10 February 1664:

‘Mr Henshaw read the History of Lignum [wood] fossils minerale, as he had translated it out of a treatise written in Italian on the subject by Francesco Stelluti. He had the thanks of the Company and his paper was ordered to be laid up, together with the printed book presented by him to the Society from Sir Robert Paston, and committed to Dr Goddard’s custody.’

Henshaw’s translation survives in our Classified Papers series (CLP/9i/13) and can now be read on our Science in the Making platform, although any mention of the aesthetic quality of the grain pattern seems to have been omitted.

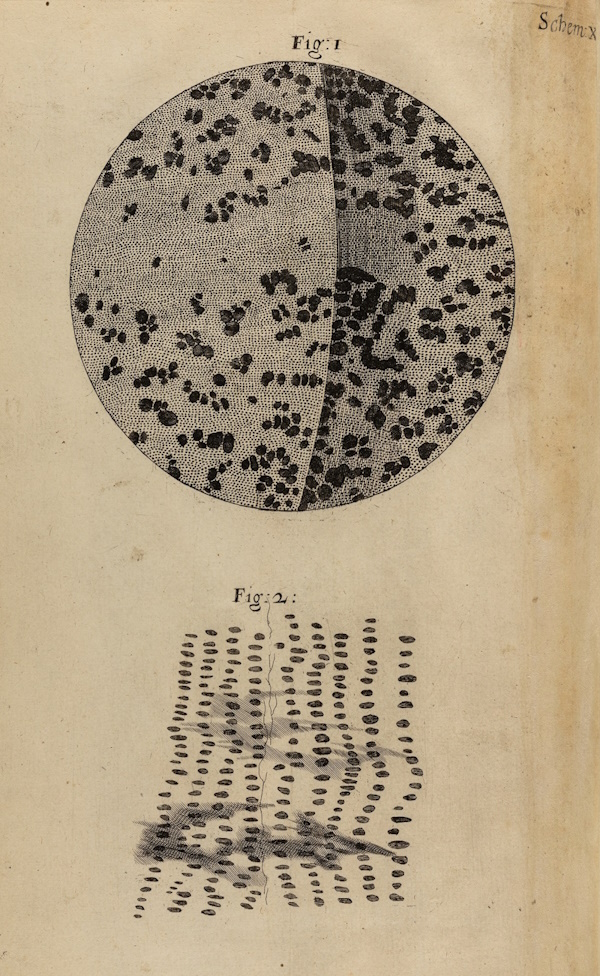

The custodian of Stelluti’s work was Jonathan Goddard, a Founder Fellow and Council member of the Royal Society. A physician by trade, Goddard was curious about wider natural philosophical subjects, and submitted papers to the Royal Society on ‘Oculus Mundi’ stones and on the texture of wood. A Journal Book entry on 26 May 1663 states that ‘Mr Hook produced Dr Goddards petrifyed wood’ which he had observed under a microscope.

Robert Hooke FRS, in turn, published his observations of ‘Petrify’d wood, and other petrify’d bodies’ in his great 1665 work Micrographia, looking at several specimens and drawing comparisons with rotten wood and charcoal. He concluded that the reason for the phenomenon was due to a process of wood being soaked in water ‘impregnated with stony and earthly particles’. These microscopical observations were significant in clarifying that petrified wood and other fossils had once been living organisms.

A microscopical study showing the pores of charcoal and petrified wood: Schem. X from Hooke’s Micrographia (RS.9434)

The original drawings of the ‘metallophyte’, done for Cesi and Stelluti, were bought by another Accademia dei Lincei member, Cassiano dal Pozzo, shortly after Cesi’s untimely death in 1630 and before the printing of the treatise. Dal Pozzo, along with his younger brother Carlo Antonio, amassed a large collection of drawings and prints over a broad range of subjects, capturing the human knowledge of the period in visual form. This great collection, known as the Museo Carteceo or Paper Museum and comprising over 10,000 artworks, was acquired by King George III in 1762 and now resides in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle.

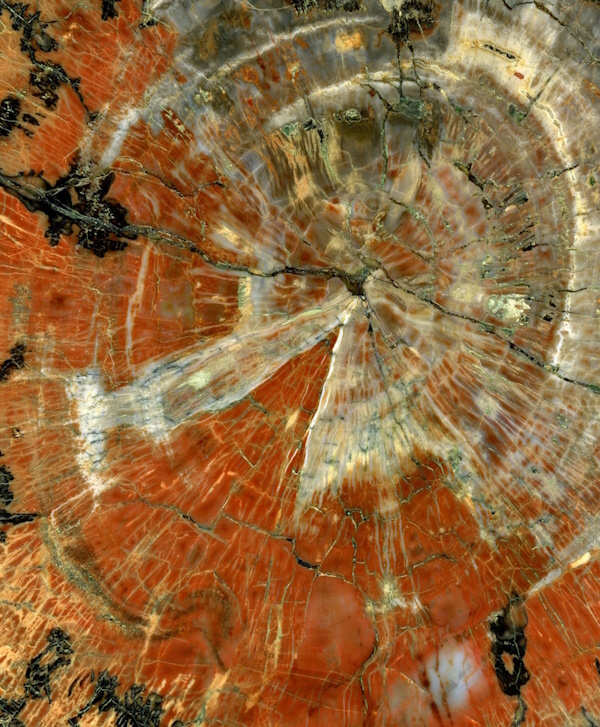

Polished slice of petrified wood by Michael Gäbler, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The allure of petrified wood still holds today, with lapidary items fetching a high price. The art of transforming fossilised wood into furniture and objets d’art was also practised by Cesi, and a fossil wood tabletop from his collection was given by dal Pozzo to George Ent FRS and shown at a meeting of the Royal Society in December 1663. Although the tabletop does not survive in our archives today, its presence at the meeting is indicative of a thriving seventeenth-century research area. The treatise by Stelluti along with the original drawings, meanwhile, are an important – and beautiful – resource for the understanding of the state of mineralogical knowledge at the time.