The Royal Society funded a series of expeditions in the 1890s to investigate the structure of coral reefs – but all did not go to plan, as Jon Bushell discovers.

While putting together a display on corals for a recent event here at the Royal Society, I found myself looking through the minutes of an interesting committee from the end of the nineteenth century. Its full title, as recorded in the Council Minutes, is the ‘Committee to superintend the arrangements for the Expedition to Bore a Coral Reef as proposed in Application D 22 (1895)’. Since this is something of a mouthful, it became generally known as the Coral Reef Committee.

Reefs are a hugely important marine ecosystem and have long been a topic of interest among the Royal Society’s Fellows. By the early nineteenth century, scientists had determined that corals could only survive in warm shallow waters, which made the presence of atolls out in the deep ocean somewhat puzzling. Charles Darwin FRS offered an explanation in The structure and distribution of coral reefs, published in 1842. Based on research conducted during the Beagle voyage, he argued that these atolls had originally formed around islands which had subsided into the ocean, leaving only the reef behind.

Darwin’s hypothesis was widely praised, but in the absence of evidential proof it also had its critics. In a letter written to Alexander Agassiz ForMemRS in 1881, a year before Darwin’s death, he mentioned his hope ‘that some doubly rich millionaire would take it into his head to have borings made in some of the Pacific and Indian Atolls; and bring home cores for slicing from a depth of 500 or 600 feet’.

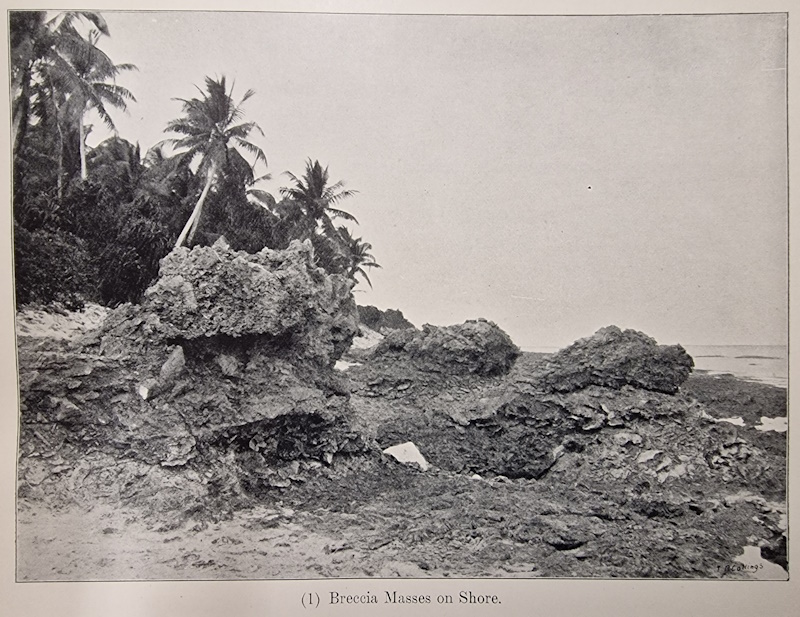

Photograph taken on Funafuti by the expedition (this and all subsequent pictures are from the 1904 Funafuti report)

Photograph taken on Funafuti by the expedition (this and all subsequent pictures are from the 1904 Funafuti report)

Such an undertaking would be immensely challenging, and it wasn’t until the 1890s that an attempt was seriously considered, spearheaded by William Sollas FRS, professor of geology at Dublin University. The atoll of Funafuti, in the Pacific Ocean north of New Zealand, was identified as a suitable site for the drilling. In 1893 Sollas convinced the British Association that the idea was worth pursuing, and arranged to borrow a diamond-tipped drill from the government in New South Wales.

When Sollas applied for a grant from the British Government in 1895 to fund the expedition, it brought the project to the attention of the Royal Society, whose Council set up the Coral Reef Committee, chaired by Thomas Bonney FRS, to oversee the arrangements. The sum of £800 was set aside to fund the expedition, and the Admiralty was approached and agreed to provide HMS Penguin to take a team to the atoll.

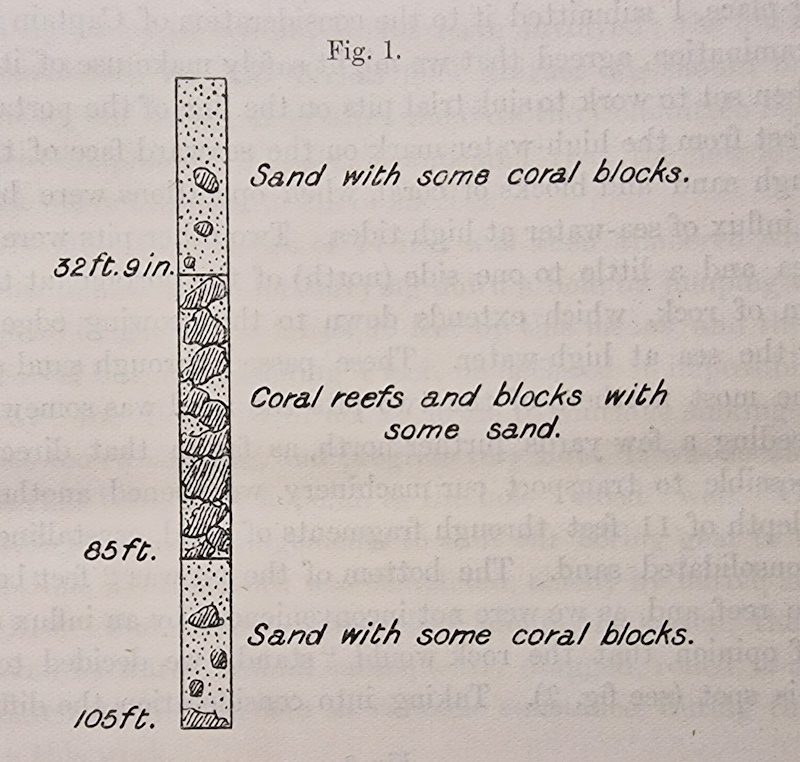

Figure showing the composition of the 1896 expedition borehole

Figure showing the composition of the 1896 expedition borehole

The party arrived on Funafuti in May 1896, with Sollas in charge. Unfortunately, despite the extensive planning it quickly became apparent that the boring would be much more challenging than anticipated. The diamond drill was best suited to penetrating very hard, compacted material, ideally of a uniform composition. The cavity-filled rock formations found on the atoll tended to dislodge the drill instead. Loose sand was an even larger problem, pouring into the boreholes faster than the team could remove it. Without proper equipment to line the hole and prevent this, the task had to be abandoned after reaching a depth of only 105 feet.

The 1896 expedition wasn’t a total failure. A topographical survey of the atoll was conducted, meteorological observations were recorded, and studies of the flora and fauna captured useful data. But the expedition had missed its primary goal of resolving the question of reef formation. A second expedition was therefore planned for the following year, this time led by Edgeworth David FRS. Armed with better equipment and ample lining material for the borehole, they anticipated greater success.

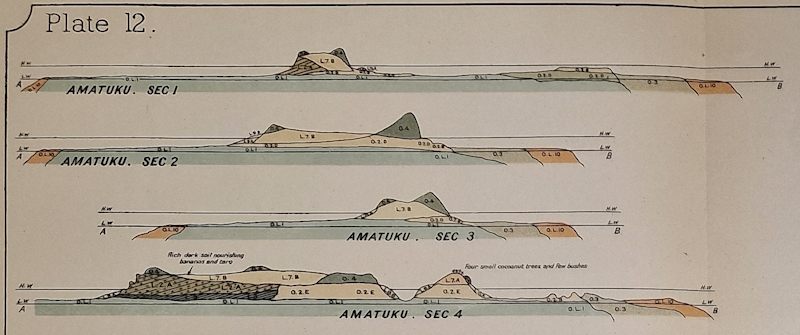

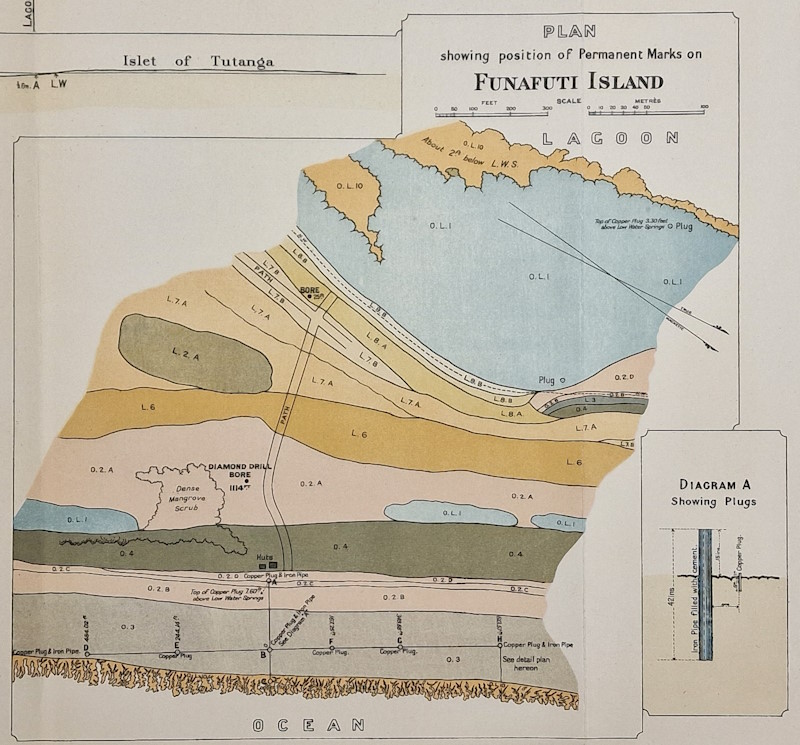

Sections from part of the geological survey of the islands of Funafuti

Sections from part of the geological survey of the islands of Funafuti

However, early results were not promising, with several accidents in the first month almost rendering the entire expedition a failure. Just three weeks after arriving in June 1897, the bore had reached 62 feet when part of the machinery broke off and became wedged in the hole. It took nearly a week to fish out the broken part so that the equipment could be repaired. Gears were regularly damaged by loose chippings thrown up by the drilling process, and at one point the main crown gearing wheel was so badly cracked that all drilling had to stop. By pure luck, a local islander had kept hold of a spare left behind by Sollas’s team the year before, without which the second expedition would almost certainly have been abandoned.

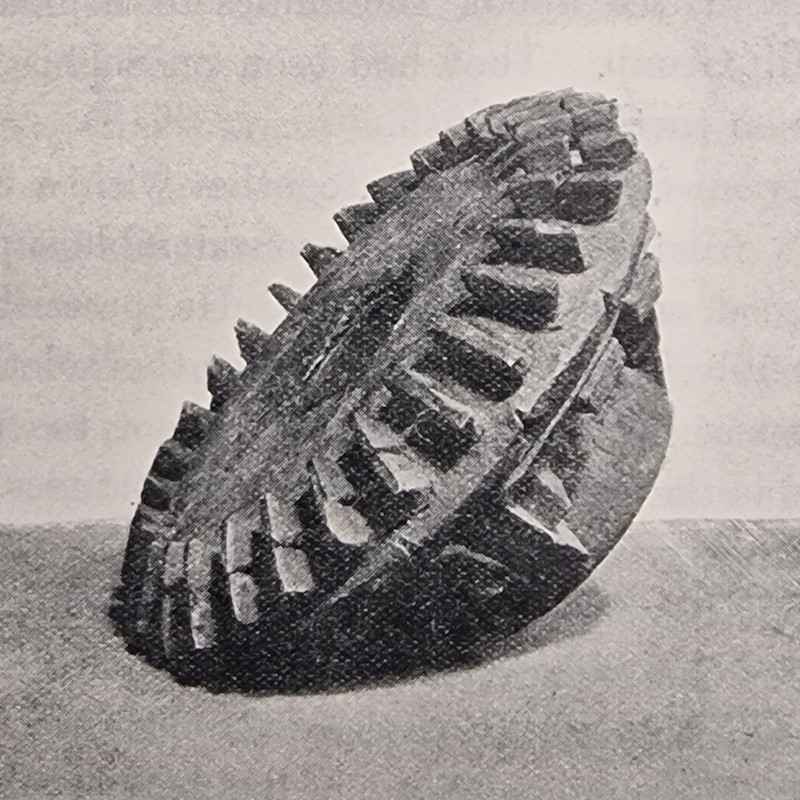

Sketch of the replacement crown gear

Sketch of the replacement crown gear

Despite the early setbacks, the expedition’s fortunes improved and by the end of 1897 core samples had been obtained from a depth of 698 feet. This exceeded the target suggested by Darwin, but the samples were still comprised mainly of fossilised corals which meant the expedition hadn’t hit bedrock. A third party returned in 1898, to reopen the borehole and continue drilling down. When the last of the drill’s replacement diamonds finally ran out in October 1898, they had collected core samples from an impressive depth of 1114 feet, almost double Darwin’s target.

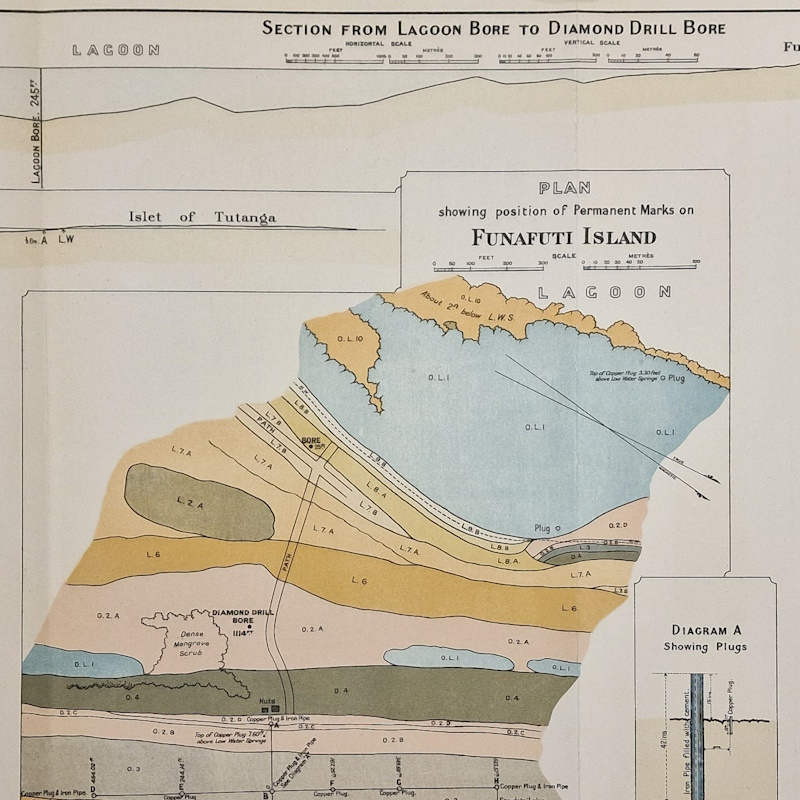

Part of plate 19, showing the location of the 1114-foot borehole

Part of plate 19, showing the location of the 1114-foot borehole

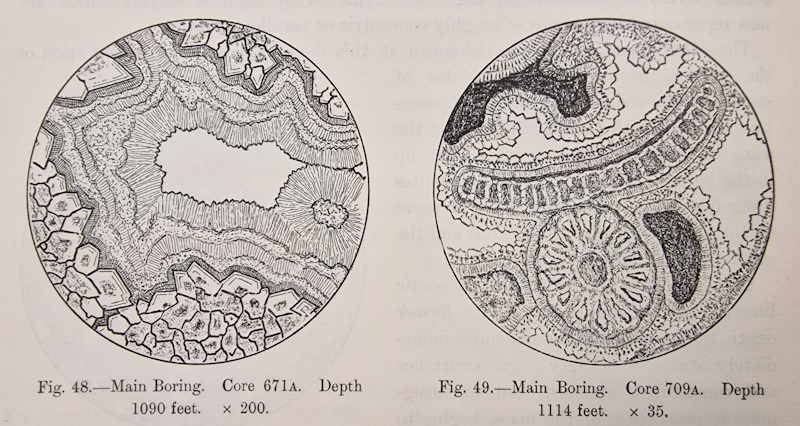

Amazingly, this still proved insufficient. The preliminary results from the core analysis were reported to the Coral Reef Committee, describing the samples as ‘Hard rock with casts of fossils, apparently an altered coral-reef rock. Many reef-building corals, seemingly in situ’. Despite three expeditions over a two-year period, the question of what lay beneath the atoll remained unanswered.

Microscopic observations of core samples taken by the 1898 expedition

Microscopic observations of core samples taken by the 1898 expedition

It wasn’t until the 1950s that Darwin’s theory was finally proven by US scientists at Enewetak Atoll, where nuclear bomb tests were being conducted. They had to bore through 4200 feet of coral to find the basalt bedrock underneath, a feat far beyond the technology available in the 1890s.

Nevertheless, the work at Funafuti was an impressive achievement for the time. The expeditions also provided a huge amount of new knowledge about the growth and development of coral reefs. A massive 400-page report, containing the results from all three visits to Funafuti, was published by the Royal Society in 1904. Drilling at Funafuti was hardly an unqualified success, but the results were anything but boring.