The Royal Society's Frankie Chappell follows in the footsteps of Charles Darwin as she investigates the nineteenth century vogue for the water cure.

Late last year I took a trip to Great Malvern, home of the famous Malvern waters.

A significant part of Malvern’s nineteenth century story is the water cure. Dr James Wilson and Dr James Manby Gulley established hydrotherapy centres in the town, with the first one opening in 1842. If you stayed at a centre, the regime would generally include showering in, bathing in and drinking the waters, walking the Malvern Hills and adhering to a strict diet.

View from the Malvern Hills. Author’s photo.

I decided to see if anything in our collections could tell me more about the nineteenth century vogue for the water cure. Looking into the history of Great Malvern it didn’t take long to find references to Charles Darwin, who was, of course, one of our most famous Fellows. While our collection doesn’t have anything by Darwin directly on the waters, there are a number of mentions in his correspondence elsewhere.

As it turns out, Darwin was a great believer in the healing powers of the waters. He took his first visit to the town to undergo the water cure by Dr James Manby Gully in 1849. In 1851, he took his daughter Anne to Malvern to undergo the treatment. Although he wrote in mid-April 1851 that things were looking hopeful, sadly she succumbed to scarlet fever just a few days later. Her headstone can still be seen in the Great Malvern Priory churchyard. Despite this, a letter from September 1863 shows that Darwin continued to believe in the medicinal effects of the waters, returning to Malvern in that year to seek help for ‘a bad amount of sickness’.

Anne Darwin’s grave in the Great Malvern Priory churchyard. Author’s photo.

We can see examples of the Malvern water cure in the Royal Society’s archives as early as the mid-eighteenth century. In a 1755 letter from John Wall M.D. published in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions, he references lines from Banister’s Breviary of the Eyes (1622):

A little more I’ll of their curing tell,

How they help sore eyes with a new found well.

Great speech of Malvern Hills was late reported,

Unto which spring people in troops resorted.

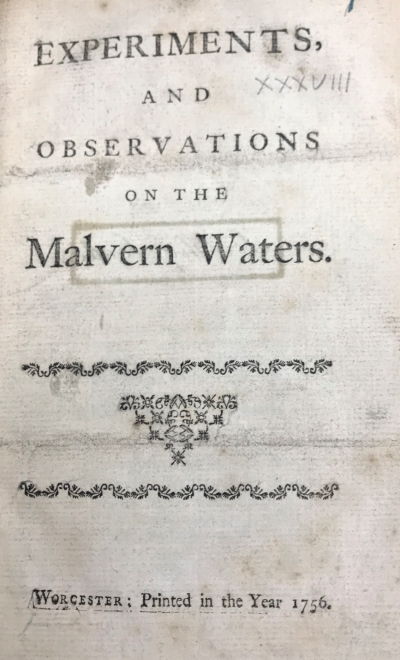

John Wall’s Experiments and observations on the Malvern waters, 1756. Royal Society Tracts XXXVIII/1.

It’s clear that in the local area at least, people had used the waters for healing for centuries. However, at this point in the eighteenth century, Wall says that the waters had not been used as extensively as they could, since they were in a place where ‘there is at present no accommodation for strangers’. Wall also mentions that there were two separate springs, one of which was thought to be better for treatment of issues with the eyes, as alluded to by Banister above.

In another letter of 1757, Wall gives some examples of the Malvern waters’ healing powers. He claims that the waters helped to cure, or relieve the symptoms of, two women suffering from ulcers and a man with elephantiasis. Most interestingly, though, Wall claims that the man, Mr. Parry, was ‘converted into a poet’ by the waters, and describes the waters as his ‘Helicon’. Ancient Greek poets considered Mount Helicon as providing inspiration, it being the location of the Muses’ sacred springs. Apparently, Mr. Parry was not the only one to draw inspiration from Malvern. C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, among others, were both touched by the natural beauty of the area as they walked the hills.

Also in our collections is an 1820 book on the mineral waters of multiple places, including Malvern, by Charles Scudamore FRS. Scudamore adds that while the waters were certainly ‘of great benefit in many of the cases that we have just enumerated’:

‘the salubrious air of Malvern, and the peaceful feelings which the quiet and charming retirement of the spot inspires, contribute in the greatest degree to strengthen the body, to calm the mind, and thus promote the general health’.

The Malvern Hills. Author’s photo.

From my experience of the hills, I am inclined to agree!

Unfortunately, I’ll never know what ills I might have cured myself of, or what epic poems I might have written under the waters’ influence, as when I visited St Anne’s Well, the water had recently been designated unsafe to drink. However, I can speak very highly of the tea houses, food shops and ‘salubrious air’ of Great Malvern.