To celebrate Peer Review Week, we've added over 1,600 Referees' Reports to our Science in the Making platform, covering the period from 1949 to 1954.

To celebrate Peer Review Week 2024, the Royal Society Collections team is adding over 1,600 historical peer review reports to the digital collection on our Science in the Making platform.

As you’ll see from the ‘Related blogs’ links at the bottom of this article, much has been said already about our unique archive of Referees' Reports. These date back to 1831 and enable researchers to retrace the history of scientific peer review. The supplementary material released this week contains some gems.

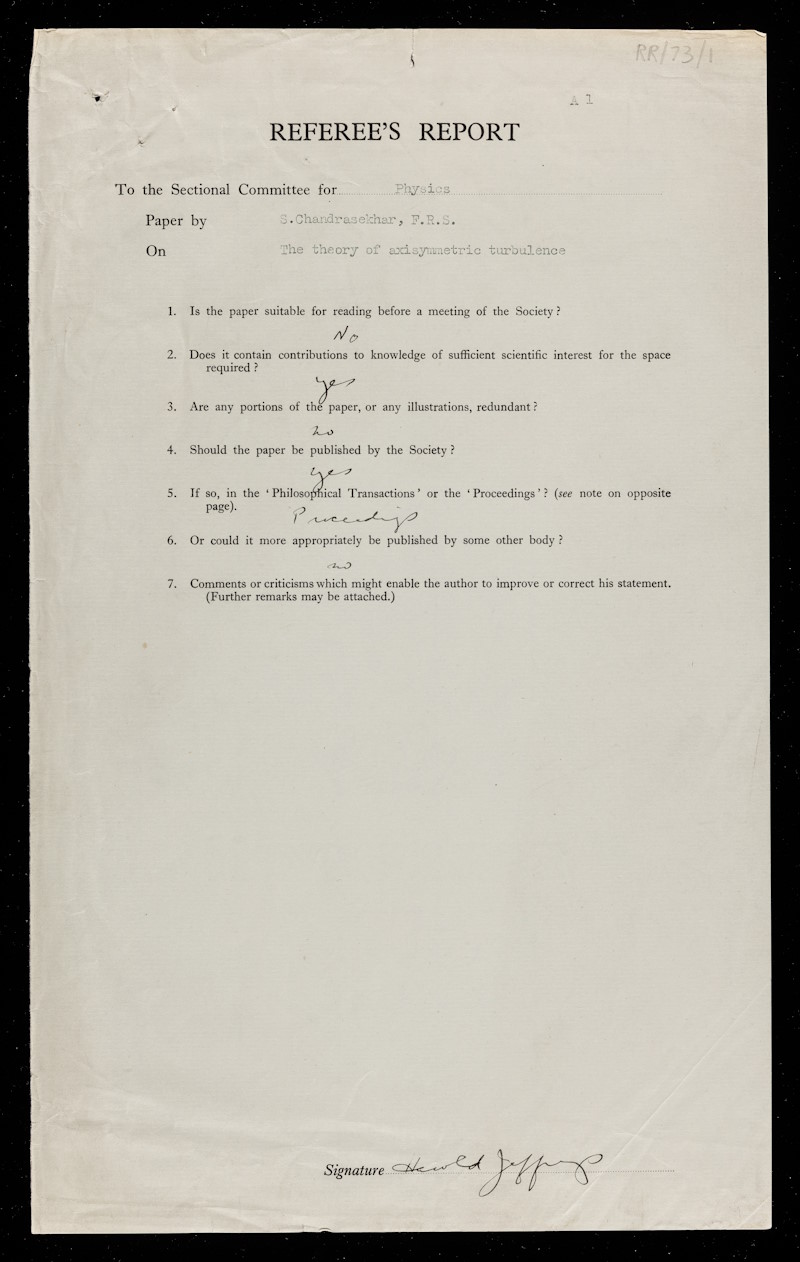

The reports cover the period from 1949 to 1954, having been closed to researchers as we keep a 70-year moratorium on peer reviews to respect confidentiality and privacy laws. By the 1950s, reviewers were filling in standardised questionnaires to assess the suitability of a given paper.

These can be repetitive and are sometimes of limited scientific value. However, the associated letters and longer reports from referees provide in-depth discussions of some of the groundbreaking papers and theories of the time.

For example, a four-page report written by J B S Haldane concerns a paper submitted by Alan Turing on ‘The chemical basis of morphogenesis’. Haldane started his review with some severity by saying, ‘before the paper is accepted, I consider that the whole non-mathematical part should be re-written’:

On the standardised printed questionnaire, Haldane sounded more conciliatory: ‘I should be glad to discuss the paper with the author, but may be leaving for India shortly. I have no objection to his being informed of my identity. In fact this might simplify matters, especially if the author saw fit to incorporate any of my suggestions [...] I regard the central idea as being sufficiently important to warrant publication. I am equally clear the paper should not be published as it stands’.

The other reviewer, Charles Galton Darwin, was more positive in his report: ‘this paper is well worth printing, because it will convey to the biologist the possibilities of mathematical morphology more definitely than has often been done hitherto’. Darwin remained sceptical of the suggestion introduced by Turing in the final paragraph of his paper, criticising Turing’s proposed ‘use of [a] digital computer’ to simulate wave theory: ‘the machinery is far too heavy for such a simple purpose.’

The reports offer an insight into how two eminent scientists received Turing’s introduction of mathematical modelling in their field. What is even more interesting though, is that the final published article seems to have taken little notice of the criticisms, leaving the comments by Darwin and Haldane unaddressed.

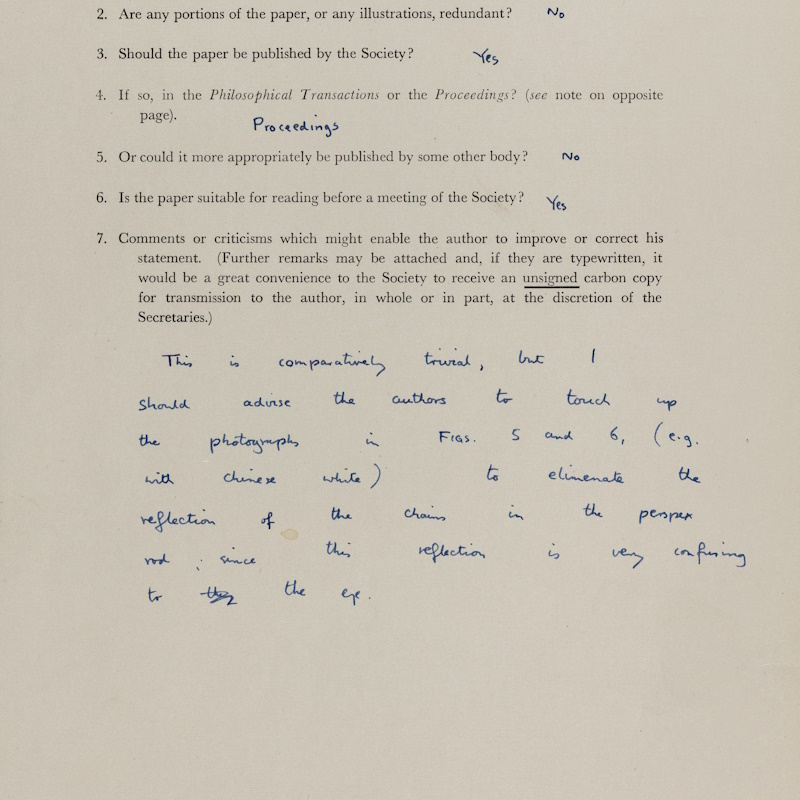

Alan Turing (IM/0004666), Charles Galton Darwin (RS.19861) and J B S Haldane (NPG x27005 © National Portrait Gallery, London – Creative Commons Licence)

Alan Turing (IM/0004666), Charles Galton Darwin (RS.19861) and J B S Haldane (NPG x27005 © National Portrait Gallery, London – Creative Commons Licence)

Looking through the minutes of the Physiology and Medical Sciences Sectional Committee, they ultimately waved the paper through for publication on 23 April 1952, noting it had been ‘favourably reported’ on by the referees. I doubt that Haldane considered his report an unequivocal endorsement, but in any case, history has side with Turing, as today’s biologists are hugely dependent on computers for modelling.

This batch of papers is also of historic significance because it marks the arrival of female scientists into the refereeing process. By 1949, eight women had been elected to the Fellowship, all trailblazers in their own fields. Of the eight, Kathleen Lonsdale and Dorothy Hodgkin acted as referees for various papers submitted to Royal Society.

Kathleen Lonsdale (RS.14152) and Dorothy Hodgkin (RS.6422)

Kathleen Lonsdale (RS.14152) and Dorothy Hodgkin (RS.6422)

Soon after her election, Kathleen Lonsdale was asked to assess papers in her field of expertise, X-ray crystallography (RR/69/174). She had evaluated an important paper by C V Raman in 1941, informally passing word to the official referees that she could easily disprove Raman’s work and that it would be best to pause publication to give Raman the chance to correct his paper. In her reports, Lonsdale acted as a diligent referee, making direct yet useful comments.

Dorothy Hodgkin features in this newly opened archive as the sole referee of a paper on one of the most significant discoveries in modern science: 'The complementary structure of deoxyribonucleic acid’ (better known as DNA) by Francis Crick and James Watson:

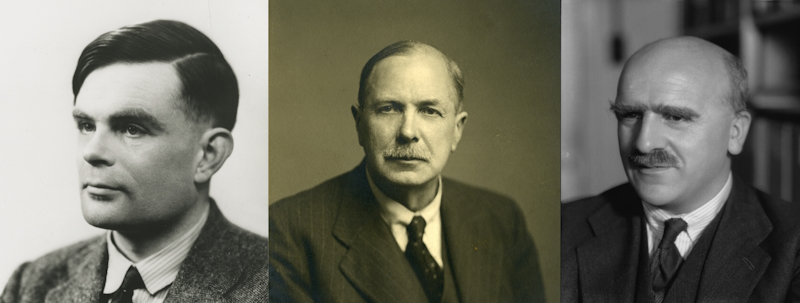

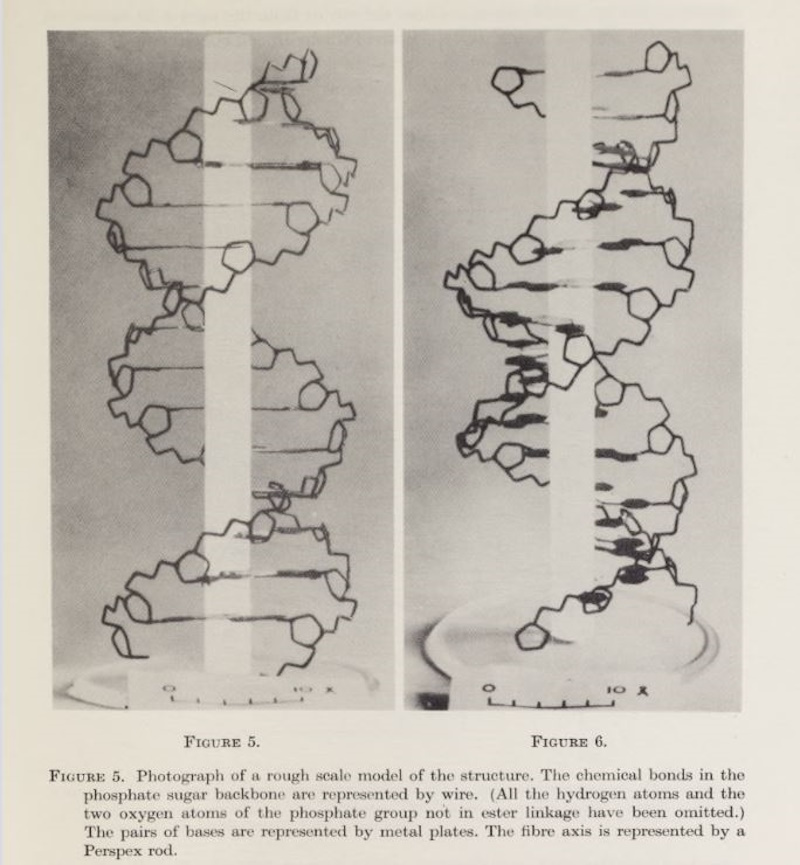

Although her review is disappointingly short, Hodgkin does make one suggestion (shown in the picture at the top of this article): ‘This is completely trivial, but I should advise the authors to touch up the photographs in figs. 5 and 6, (e.g. with Chinese white) to eliminate the reflection of the chairs in the perspex rod: since this reflection is very confusing to the eye’. Crick and Watson seem to have followed this advice, as the rod appears as a clear white line in the published photograph:

Plate from 'The complementary structure of deoxyribonucleic acid' (1954)

Plate from 'The complementary structure of deoxyribonucleic acid' (1954)

Crick and Watson were the only authors named on this paper, sidelining the critical role played by Rosalind Franklin in the research, in spite of the fact that she presented the discovery of DNA with others at Royal Society Soirées in the same year. But, for some sense of justice, Hodgkin also refereed Franklin’s paper on ‘Crystallite growth in graphitising and non-graphitising carbons’, though noting that she felt ‘incompetent’ to review the paper as she lacked the appropriate expertise:

The general rule at the time was that only Fellows could act as referees for the Society’s journals. For specific topics not well represented in the Fellowship, it was often necessary to resort to outside help. When the eminent female mycologist Lilian Hawker submitted a paper, the Society turned to two non-Fellows in the field of mycology, Richard Dennis and Elsie Wakefield. Wakefield was highly regarded, serving as the Deputy Keeper of the Herbarium at Kew Gardens, where records of her extensive work on British fungi and her fabulous watercolours are still kept. Both referees provided sterling commendations of Hawker’s work (RR/80/26, RR/80/27 and RR/80/28). I was slightly saddened to find out that Hawker missed out on election to the Fellowship on two occasions, but at least her work remains in our journals.

Many of the leading scientists of the 1950s are present – either as authors or referees – in this latest crop of Referees’ Reports. I’ve focused on the female voices in peer reviews, but it’s important to remember that women scientists were only a very small minority of contributors at this time. Those mentioned here were some of the first to break through the glass ceiling, which makes it all the more important to celebrate them in Peer Review Week 2024.