Louisiane Ferlier reports on the discoverability of non-Fellows in the Royal Society's Science in the Making resource.

Since we launched the platform that showcases our digitised manuscripts, Science in the Making, I’ve been mindful that our data has reinforced some of the imbalances in the Royal Society’s history. How, then, should we address this?

Up to the present day, the Royal Society’s Fellowship has not been as diverse as our wider society. If we just think in terms of gender, of the 7,482 people recorded in our database of past Fellows, only 58 were women (including two of our Royal patrons) – not even 1% of the overall total. You can read more about the topic in this article celebrating the 50th anniversary of the first election of women to the Society. Equality, diversity and inclusion are at the heart of the Society’s work today, but the fact remains that only around 12% of the Society’s current Fellows are women.

The Royal Society’s archives make clear that the scientific contributions of women and other under-represented groups are threaded through the organisation’s history. The attendance of Margaret Cavendish and Francis Williams at weekly meetings around 60 years apart are two very well-known examples of stories beyond exclusion from the Fellowship. My thoughts therefore focused on improving the discoverability of people from under-represented groups, as readers explore our archives digitally.

Let me start with the data problem: the Royal Society’s archive catalogue includes authority files containing short biographies of each of our historical Fellows. These are a fantastic resource, allowing Fellowship information to be accessed easily when searching through our platform. In contrast, however, the non-Fellows who contributed to our archive have no authorities; these include some very famous scientific names, from Caroline Herschel to Marie Curie.

Marie Curie receiving an honorary doctorate from the University of Birmingham at the British Association Meeting, 1913 (IM/007198)

Marie Curie receiving an honorary doctorate from the University of Birmingham at the British Association Meeting, 1913 (IM/007198)

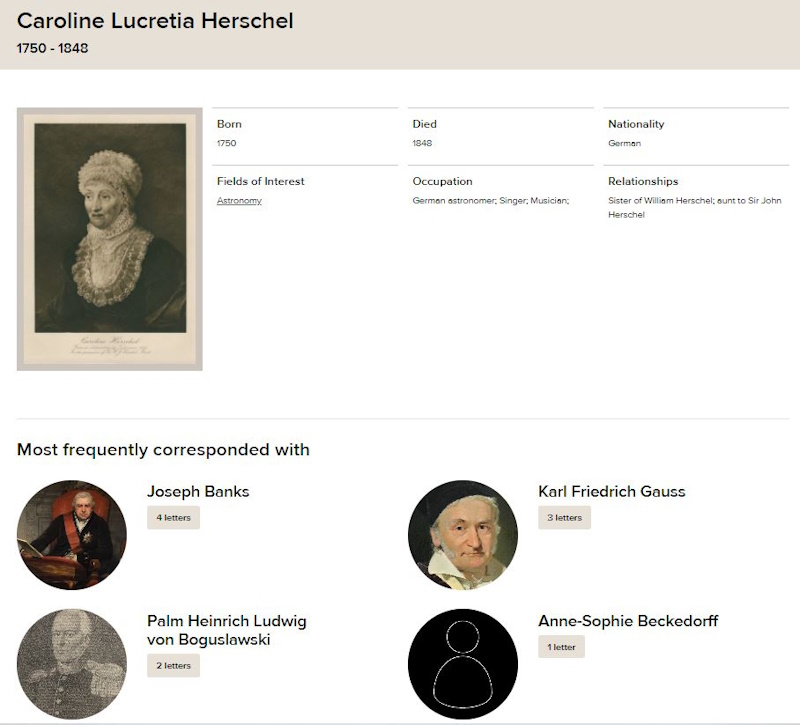

To redress this data bias, a dataset of non-Fellows has begun to capture some information about them, including short epithets noting their field of activity and nationality, thereby improving their visibility. We started with the data created for the Herschel correspondence, double-checking the epithets we’d produced for all senders and recipients of letters, whether Fellows or not. It’s worth noting that 6% of Herschel’s correspondents were women, a much higher figure than is found with most of the historical Fellowship. If you want to hear more about the women of science in Herschel’s networks, catch up on this recent Cassyni seminar on the subject.

The new non-Fellows dataset contains the name, dates of birth and death – or at least ‘date(s) active’ – occupation, research field, and familial relationships where pertinent. We use the Virtual International Authority File to connect the person to Wikidata so that people can read further, and allowing images to be used on our website.

Person page for Caroline Herschel on Science in the Making

Person page for Caroline Herschel on Science in the Making

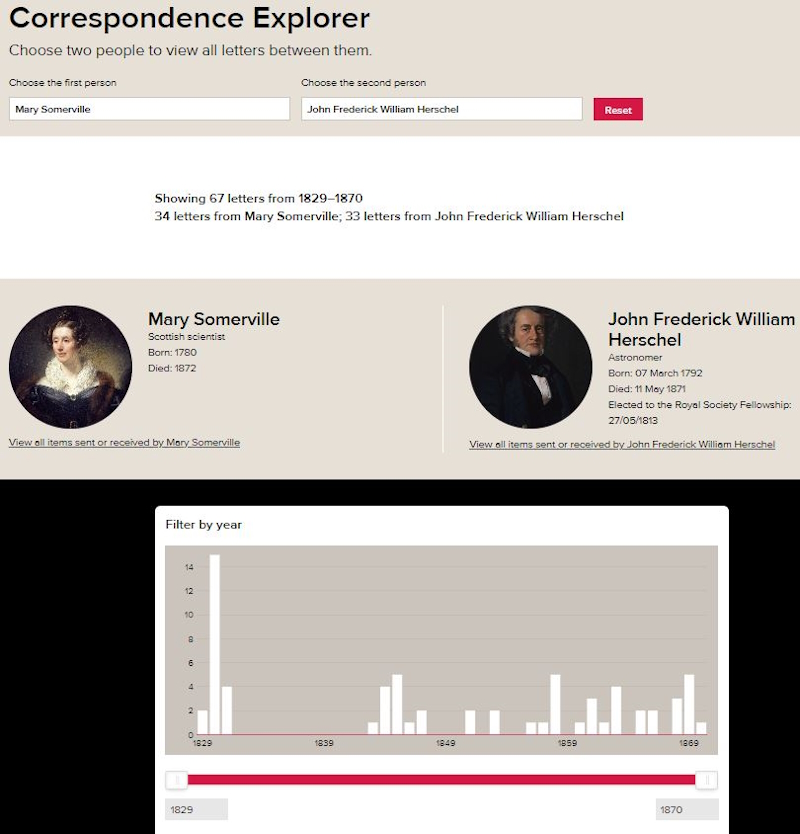

You can now filter people by person status (‘Fellow’ or ‘Non-Fellow’) in the search, and find all items related to a non-Fellow from their personal page. The correspondence explorer displays Fellows and non-Fellows in a more equal way:

Correspondence explorer – example of the letters between Mary Somerville and John Herschel

Correspondence explorer – example of the letters between Mary Somerville and John Herschel

This is very much a work in progress, and it will take us a while to go back through the catalogue and identify as many non-Fellow contributors as possible in other archival series. I’m delighted to say that, as of today, I have added all the non-Fellows who sent the correspondence collected in our Early Letters series, including Galileo Galilei. There are at present a total of 1,520 non-Fellows and 3,153 Fellows, so we’re certainly improving visibility and representation!