Ainsley Vinall tells the story of the astronomer Alexander Aubert FRS, the subject of an oil painting recently purchased by the Royal Society.

The Royal Society has been collecting portraits of its Fellows since the seventeenth century and we now have over 200 oil paintings of scientists, physicians and engineers in our collection.

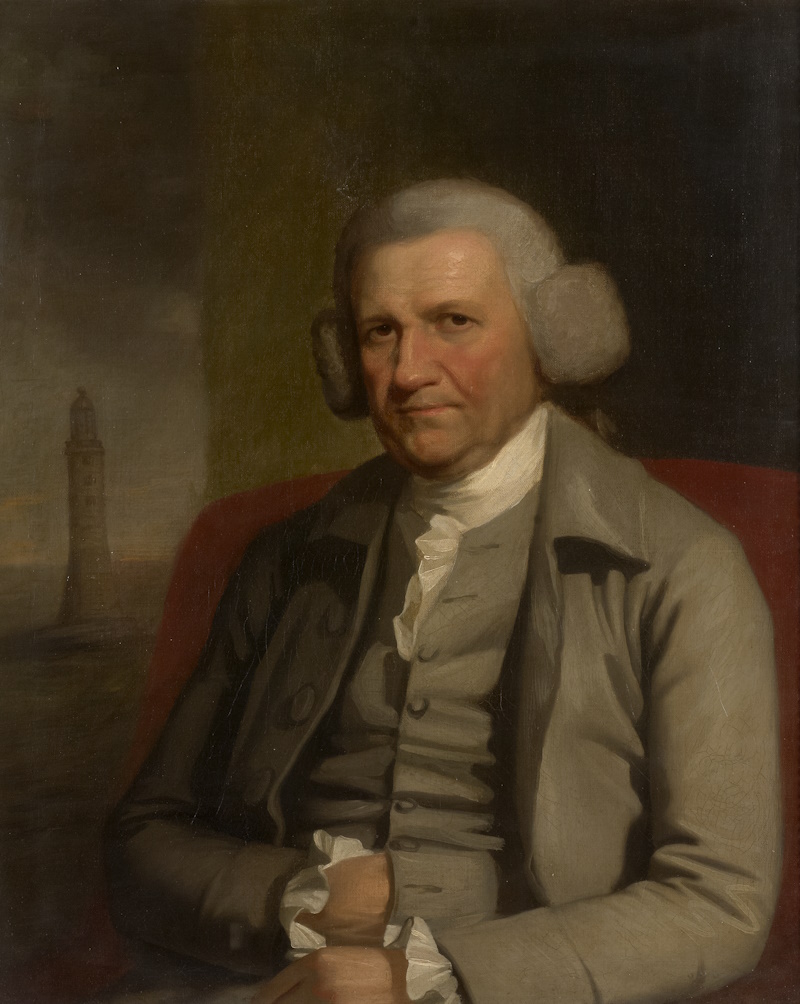

We occasionally commission new portraits of contemporary Fellows, mostly focusing on past Presidents and on encouraging greater gender diversity, but we also keep an eye out for historic paintings to fill in the gaps. Towards the end of last year, we spotted a portrait of Alexander Aubert FRS (1730-1805) up for sale and were able to purchase it at auction.

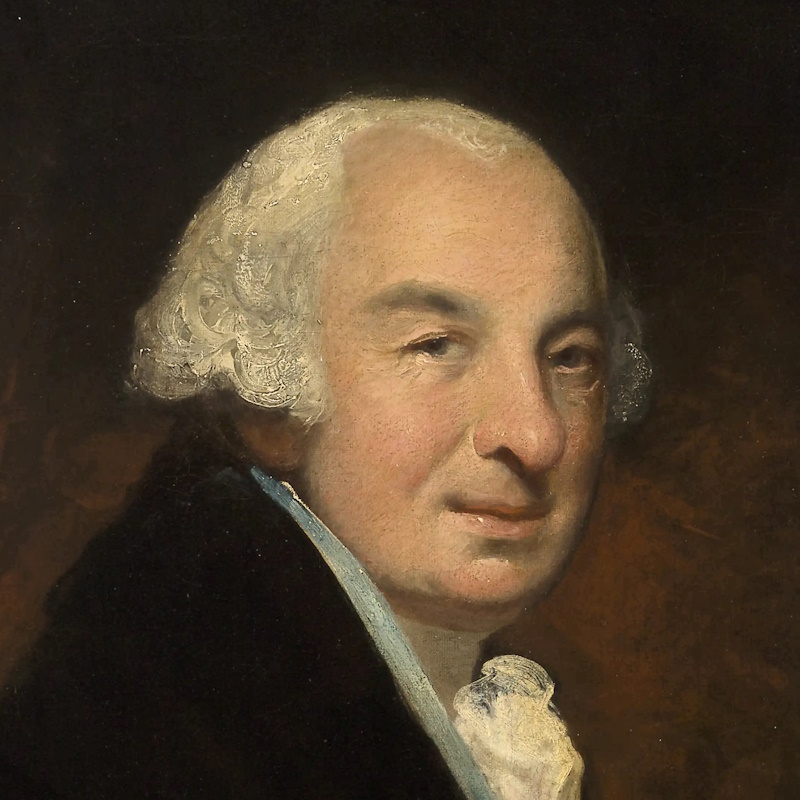

The picture shows Aubert, an astronomer and businessman, in his sixties. He is rosy-cheeked and half-smiling in a black jacket and silk cravat. A red curtain fills most of the background, but there is a small reference to his astronomical work as the view out of the window shows a rugged landscape under a dark night sky. The portrait was painted in 1798 by Samuel Drummond (1766-1844), a prolific portraitist who was employed by The European Magazine to create likenesses of well-known figures for engraving to illustrate short biographies.

Alexander Aubert, by Samuel Drummond, 1798 (P/0294)

Alexander Aubert, by Samuel Drummond, 1798 (P/0294)

The son of a Huguenot refugee father, Alexander Aubert was born in London, studied in Geneva and spent most of his youth travelling around Italy and Switzerland. While staying in Geneva with some family members he observed the Great Comet of 1744, sparking a lifelong passion for astronomy. At the age of twenty-three he finally settled in London and joined his father at the London Assurance Company.

He excelled at the insurance firm, eventually rising to governor, and amassed a small fortune which he spent on fine telescopes. In 1771 he established a private observatory at Loampit Hill in Deptford which he equipped with instruments by John Bird (1709-1776), James Short FRS (1710-1768), Jesse Ramsden FRS (1735-1800) and John Dollond FRS (1706-1761). With such an impressive collection of telescopes, it was likely the finest private observatory in the country.

Aubert’s name soon spread in astronomical circles and he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1772. He became a popular and active member, submitting papers to the Philosophical Transactions, attending dinners of the Royal Society Club, serving on Council as well as numerous committees, and even offering his insurance services to other Fellows. Among the letters he wrote on scientific subjects, our archives also include a quote he compiled in 1787 for Royal Society President Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) giving the insurance premium on a brick house.

Although he made no major discoveries, Aubert was a reliable and astute astronomer who recorded the precise locations and sidereal times of his observations. He was a witness to the 1783 Great Meteor and sent his account of it to the Royal Society. Unfortunately, he was not at his observatory when the meteor appeared and had to estimate its elevation and trajectory while on the move. His report, published in the Philosophical Transactions, reads:

‘I was on horseback returning to my observatory […] when I was much surprised on perceiving suddenly a kind of glimmering light resembling faint, but quickly repeated flashes of lightning, soon […] I saw it form into a large luminous body like electrical fire with a tinge of blue round its edges.’

'Of the same meteor', by Alexander Aubert, 1783

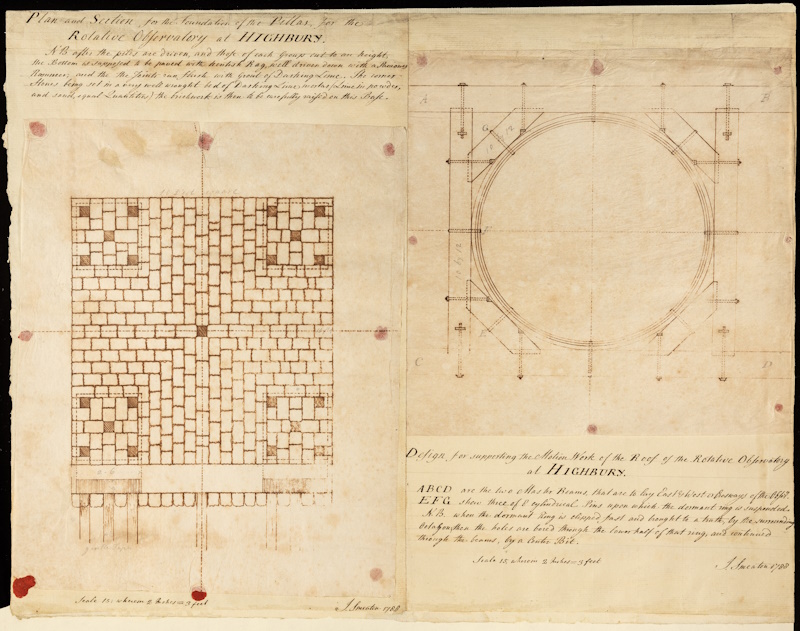

In 1788 Aubert purchased Highbury House in Islington and established a new observatory which he designed in collaboration with the engineer John Smeaton FRS (1724-1792). The original plans for the foundation pillar and revolving roof are held in the Royal Society’s archives; the sturdy central pillar insulated the delicate instruments from vibrations while the revolving roof protected them from the weather when not in use.

Plans for the Rotative Observatory at Highbury, by John Smeaton, 1788 (JS/4/26v)

Plans for the Rotative Observatory at Highbury, by John Smeaton, 1788 (JS/4/26v)

Aubert and Smeaton were close friends and had worked together throughout the 1780s on the design of Ramsgate Harbour, Aubert as chairman of the trustees with Smeaton as chief engineer. In 1789 they surveyed the foundations of the structure in a cast-iron diving bell of Smeaton’s own design, staying underwater for 45 minutes with fresh air pumped down to them from a boat on the surface.

Aubert made many friends amongst the Fellowship of the Royal Society, entertaining guests at Highbury House and visiting other scientists at their own homes. He was also a regular at the Royal Society Club, dining with the group 36 times in 1791, and even presenting the club with its own voting box and ballot balls for electing new members.

Aubert’s popularity with the senior Fellows meant that when John Pringle FRS (1707-1782), announced he was stepping down as President of the Royal Society in 1778, Aubert was his preferred candidate as a successor. However, Sir Joseph Banks, by then a famous traveller and naturalist who had at last settled in London, was also keen on the role. In a letter to Banks, Daniel Solander FRS (1733-1782) wrote of John Pringle that ‘it is true that he has given hints about Mr. Aubert, but all look to you.’ Indeed, after canvassing for support amongst his friends, Banks emerged as the frontrunner and was elected as Pringle’s successor in November 1778. As Banks went on to serve for almost 42 years, Aubert never had another opportunity to stand for President.

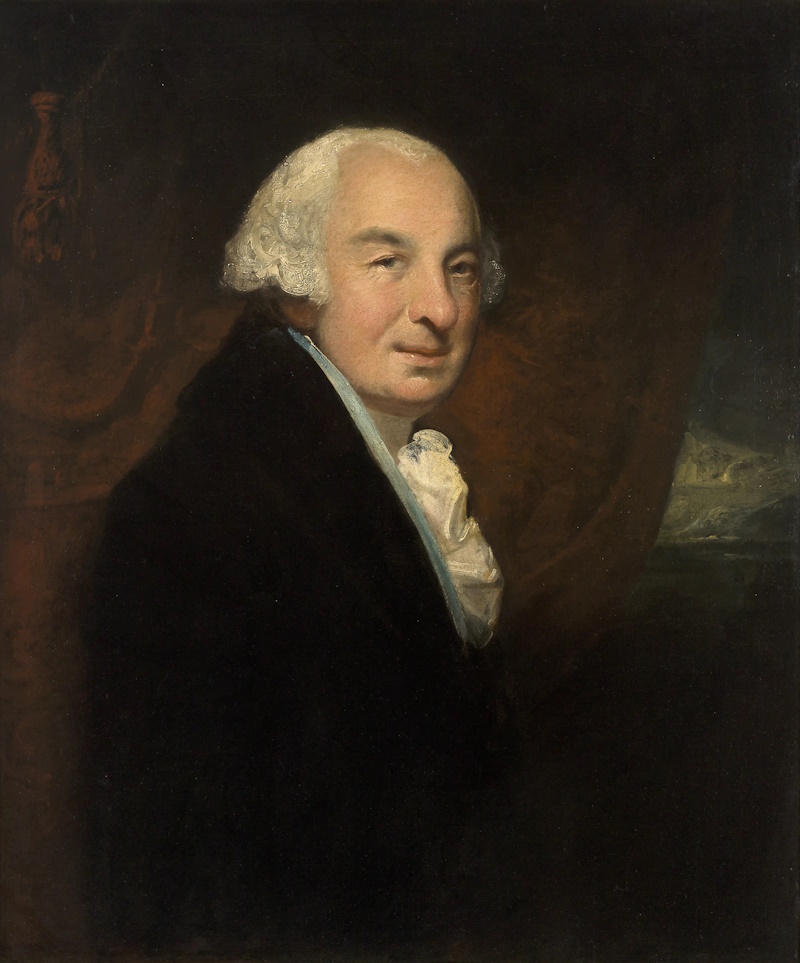

John Smeaton, by Mather Brown (1761-1831), c.1788 (P/0119)

John Smeaton, by Mather Brown (1761-1831), c.1788 (P/0119)

The addition of his portrait to our collection gives us the opportunity to highlight Alexander Aubert’s contributions to the history of the Royal Society. And there’s one final link: although he was a humble man, Aubert was an art collector himself and recognised the importance of portraiture. In 1799 he gave a painting of his ‘much esteemed friend’ John Smeaton to the Society, in the wish that the donation would help to preserve the memory of the great civil engineer. Over 200 years later, Aubert’s own portrait joins that of his dear friend.