Keen towpath rambler Jon Bushell looks at the construction, decline and resurrection of the Basingstoke Canal, and the possible involvement of Royal Society Fellow John Smeaton.

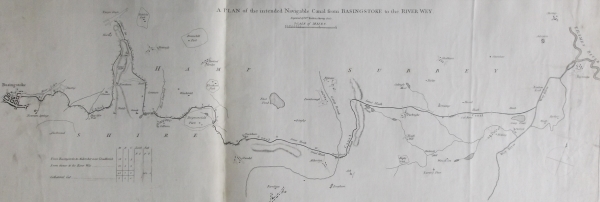

I recently retrieved one of our volumes of John Smeaton’s design drawings from the archive, in the course of dealing with an enquiry. While carefully folding away a three-metre-long set of river navigation plans, I spotted a curious little map relating to a rather unsuccessful eighteenth-century waterway, the Basingstoke Canal.

Swan Bridge over the Basingstoke Canal. The original eighteenth century bridge had to be replaced in 1921 when it collapsed after a landslip.

I’m quite familiar with a couple of sections of the canal thanks to my regular rambling (the colour snaps in this article are from a walk I did last November), and I was therefore a little surprised to find this among Smeaton’s works. His name is not one that generally comes up in connection with this particular canal, so I was intrigued enough to dig a little deeper.

Plans to build a canal connecting Basingstoke to London had been floating around for some time, as improving access to the city’s markets was seen as crucial for developing Hampshire’s agricultural economy. An initial proposal in 1769 suggested a route connecting Basingstoke to Maidenhead, joining the river Thames near Monkey Island, at the village of Bray. This met with considerable opposition from local landowners, and the scheme was abandoned in 1771.

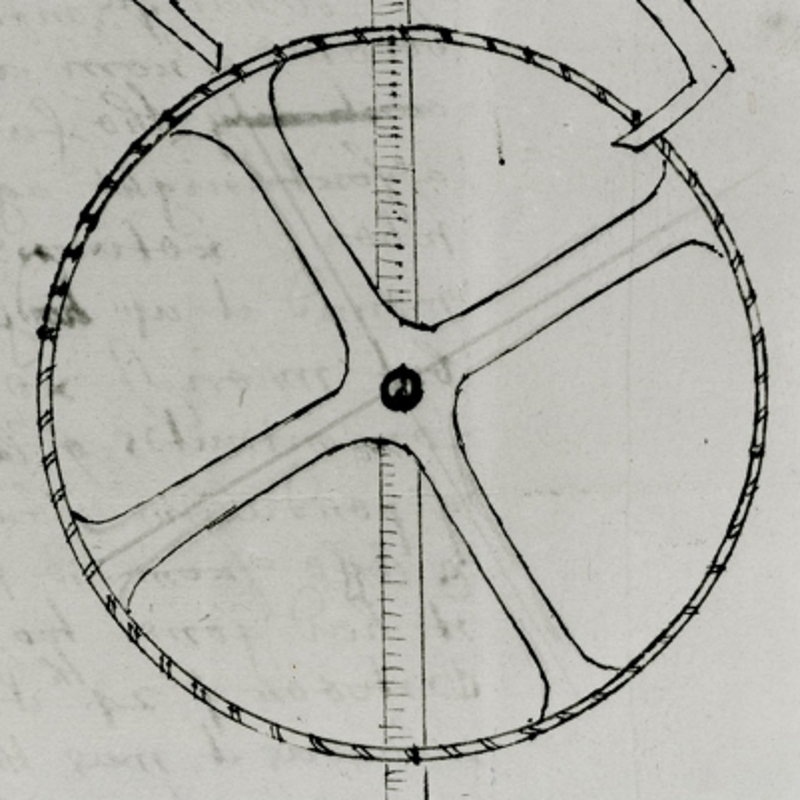

John Smeaton’s plan of the proposed route for the Basingstoke Canal, JS/6/97.

Smeaton’s map is undated, but it depicts the second possible route for the canal, proposed in 1776. The new plan was to connect Basingstoke to London by joining the River Wey to the east. A 1778 edition of the Gentleman’s Magazine happily declared that the new plan was facing less opposition than the earlier proposal, ‘for out of the great number of different properties this canal in a course of 43 miles must go through, there are but two dissenting voices.’

The extent of Smeaton’s involvement with the Basingstoke Canal is a bit of a mystery. Certainly, he was not responsible for the initial survey of the new 1776 route, as that task was given to an engineer named Joseph Parker. Given the presence of the map among Smeaton’s drawings, it’s possible he had a supervisory role, or he may have intended to oversee the construction work. Whatever the case, the project was put on hold once again, this time due to lack of funding, as the strain of the American War of Independence led to a financial crisis in Britain.

A stretch of the Basingstoke Canal near Odiham.

When work finally got underway in late 1788, Smeaton was busy with other projects, not least his ongoing improvements to Ramsgate Harbour. William Jessop, one of Smeaton’s former assistants, was the appointed surveyor and consultant engineer instead. Construction of the entire waterway took six years to complete, and Smeaton died in 1792 before the canal was actually completed.

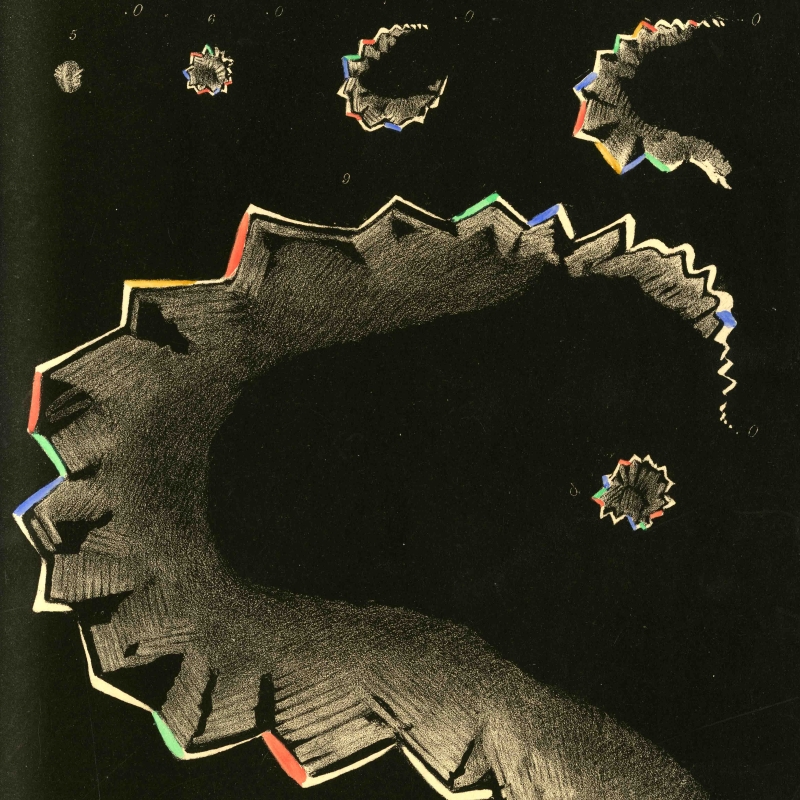

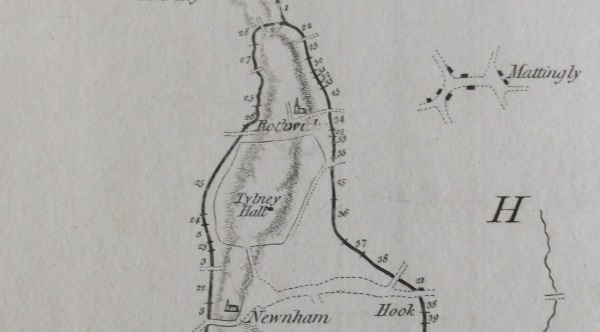

The final route remained largely unchanged from Parker’s 1776 plan, with one notable exception. Originally, the canal was to loop around Tylney Hall near Odiham, but the Earl of Tylney objected to the canal cutting the Hall off from most of his surrounding land; no doubt he was one of the ‘dissenting voices’ mentioned in the Gentleman’s Magazine. The route was altered to include a kilometre-long tunnel underneath Greywell Hill, to the south of Tylney.

The intended loop of the canal around Tylney Hall (detail from Smeaton’s plan, JS/6/97).

The canal finally opened to traffic in 1794, but it was not particularly advantageous to the region. There were certainly some modest economic benefits thanks to the improved trade in timber, malt and flour to London. However, construction costs had been higher than anticipated, due to a shortage of labour and materials caused by the American war. Worse still, low water levels left sections of the canal unnavigable during the summer. Competition from the railways in the nineteenth century was the final nail in the canal’s coffin. The London and Southampton railway followed the exact same route as the Basingstoke canal between Weybridge and Basingstoke, so when the line opened in 1840, the canal’s fortunes were sunk.

The amount of traffic on the canal continued to dwindle, and by the early 1900s it had all but dried up. It was used so rarely that in 1913 the only remaining trader on the canal, A J Harmsworth, attempted to travel the entire length in order to prevent the navigation rights expiring. In 1932, the western end of the Greywell Tunnel collapsed, completely cutting off the last five miles of the canal and making it impossible to reach Basingstoke by water.

The North Warnborough Lift Bridge, which has to be operated by hand.

The Basingstoke Canal might have been an economic failure in the nineteenth century, but has gained a new lease of life in modern times. Surrey and Hampshire County Councils, along with a small army of volunteers, began restoring the canal in the late 1970s, and today it is popular with walkers, cyclists and canal boat owners. Significantly, the waterway is also a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest, recognised as one of the most biodiverse environments in Britain for aquatic plant life, along with a huge variety of insect and bird species. Water positive outcome!

I might have gone overboard with the water-based puns in this one.