Katherine Marshall looks at the life of Lady Margaret Huggins, and her significant work in spectroscopic astrophotography in the late nineteenth century.

During the course of my research for our current Royal Society Library exhibition Light: a colourful history, I came across an intriguing communication from the Society’s Assistant Secretary Robert Harrison to Lady Margaret Huggins, dated 21 May 1912.

The letter noted the safe receipt of her box containing ‘the Fraunhofer apparatus’. Contemporary records do not mention any official donation of such an instrument, and the absence of the historical object itself, with no further correspondence, makes this letter a bit of a mystery. This is rather disappointing, since its presence in the Society’s collections would offer a tangible link to a woman who played an important role in spectroscopic astrophotography in the late nineteenth century, using the very apparatus which laid the foundation for the field of spectral analysis.

Fraunhofer’s apparatus for investigating the properties of coloured spectra, and especially for exhibiting the fixed lines in the spectrum (MOB/040)

Fraunhofer’s apparatus for investigating the properties of coloured spectra, and especially for exhibiting the fixed lines in the spectrum (MOB/040)

It’s possible the ‘Fraunhofer apparatus’ was similar to that shown above, presented to the Society by Joseph von Fraunhofer himself in the early nineteenth century and listed among the instruments in the Society’s possession in 1834 (MDA/H/9). Placing this in the home of the Society, and available to its Fellows, was a clever marketing trick on Fraunhofer’s part – a ‘try before you buy’, if you like.

As well as donations like this, the Society funded the purchase of instruments for use by its Fellows well into the mid-twentieth century. One such recipient was William Huggins, who secured the funding for a ‘Great Grubb Equatorial’ telescope in 1870. At roughly £2000, this was the most the Society ever spent on an instrument for an individual Fellow, and it enabled Huggins to carry out spectrum observations with his future wife Margaret.

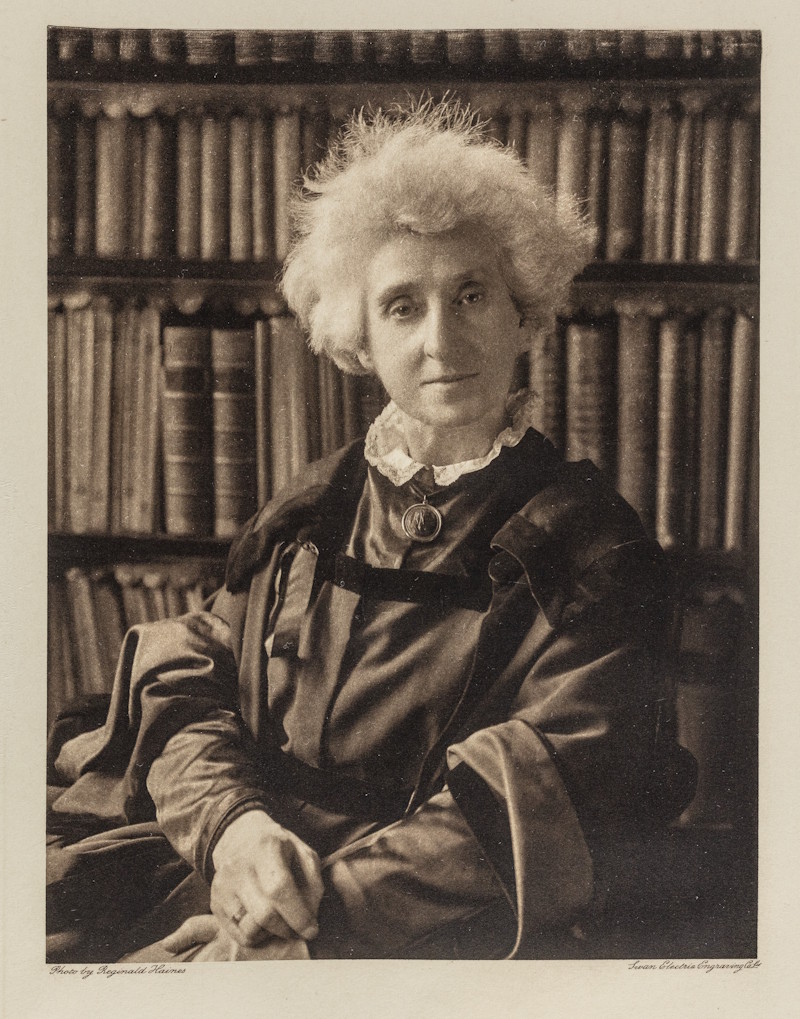

Portrait of Margaret Huggins, photogravure by Swan Electric Engraving Co. Ltd after a photograph by Reginald Haines (RS.21901). Frontispiece to The scientific papers of Sir William Huggins (1909)

Portrait of Margaret Huggins, photogravure by Swan Electric Engraving Co. Ltd after a photograph by Reginald Haines (RS.21901). Frontispiece to The scientific papers of Sir William Huggins (1909)

Dame Margaret Lindsay Huggins, née Murray (1848-1915), was an Irish-born astronomer, whose interest in stargazing began during her childhood, when she spent time with her paternal grandfather after the early death of her mother and her father’s remarriage. It is not known how she first met her future husband, but it is likely she knew of the astronomer (and later President of the Royal Society) through the scientific journals she read as a young woman. They were married in 1875 when she was 27 and he 51, and thus began an important scientific collaboration.

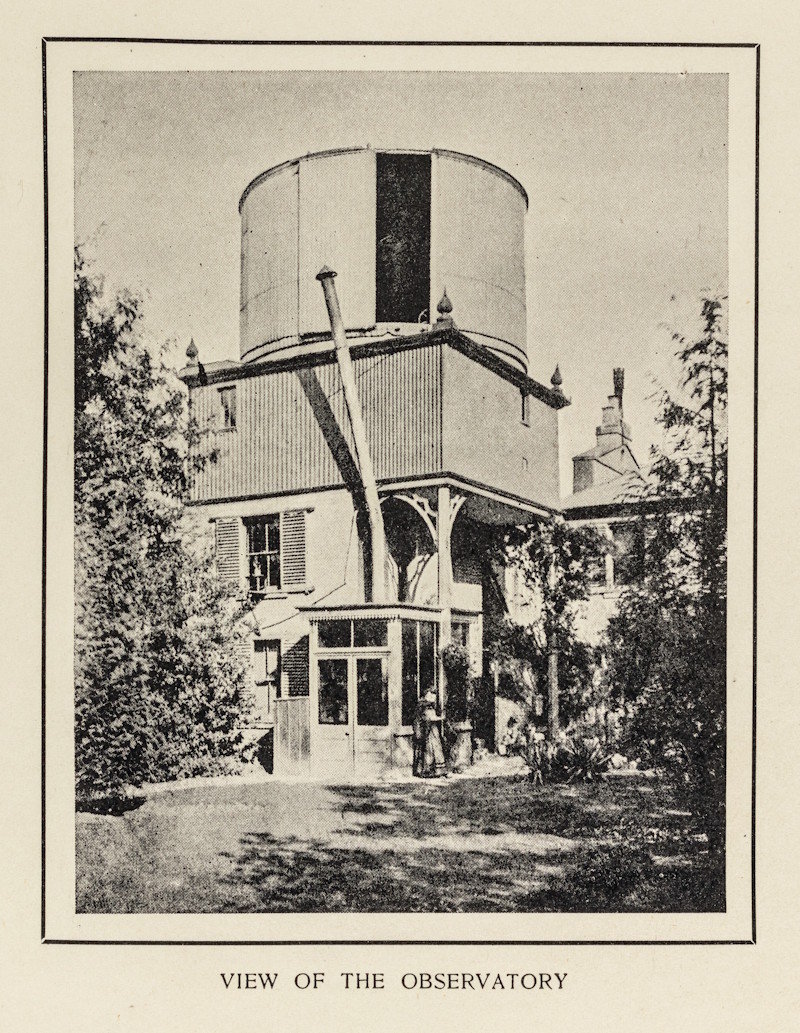

Margaret Huggins and the observatory at Tulse Hill, London (RS.21903). Frontispiece to The scientific papers of Sir William Huggins (1909)

Margaret Huggins and the observatory at Tulse Hill, London (RS.21903). Frontispiece to The scientific papers of Sir William Huggins (1909)

William credited his wife as his ‘able and enthusiastic assistant’. Having studied their observatory workbooks, however, biographer Barbara J Becker believes their collaboration to have been much more. Margaret took an active role at their personal observatory in Tulse Hill, London, where the ‘Great Grubb’ was installed. She carried out observations, which involved long hours looking though a spectroscope and had a fatiguing effect on the eye.

It is not surprising, then, that she used her interest in photography to develop new methods for capturing spectral patterns, thereby reducing eyestrain in lengthy sessions at the telescope. She refined the dry plate (silver gelatin) process to produce images which showed absorption lines clearly enough to record the spectral signatures of nebulae and stars.

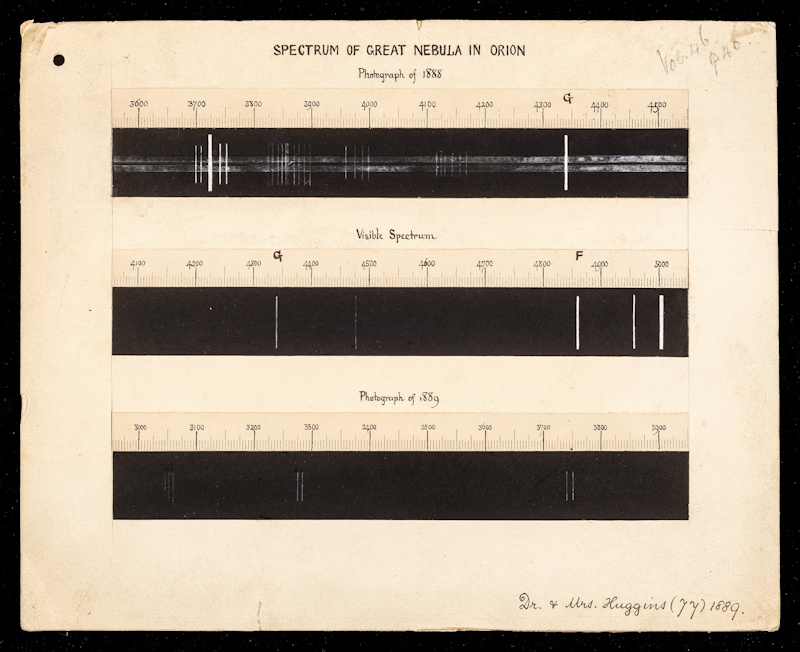

‘On the spectrum, visible and photographic, of the great nebula in Orion’ by William Huggins and Margaret Huggins, 1889. PP/14/4

‘On the spectrum, visible and photographic, of the great nebula in Orion’ by William Huggins and Margaret Huggins, 1889. PP/14/4

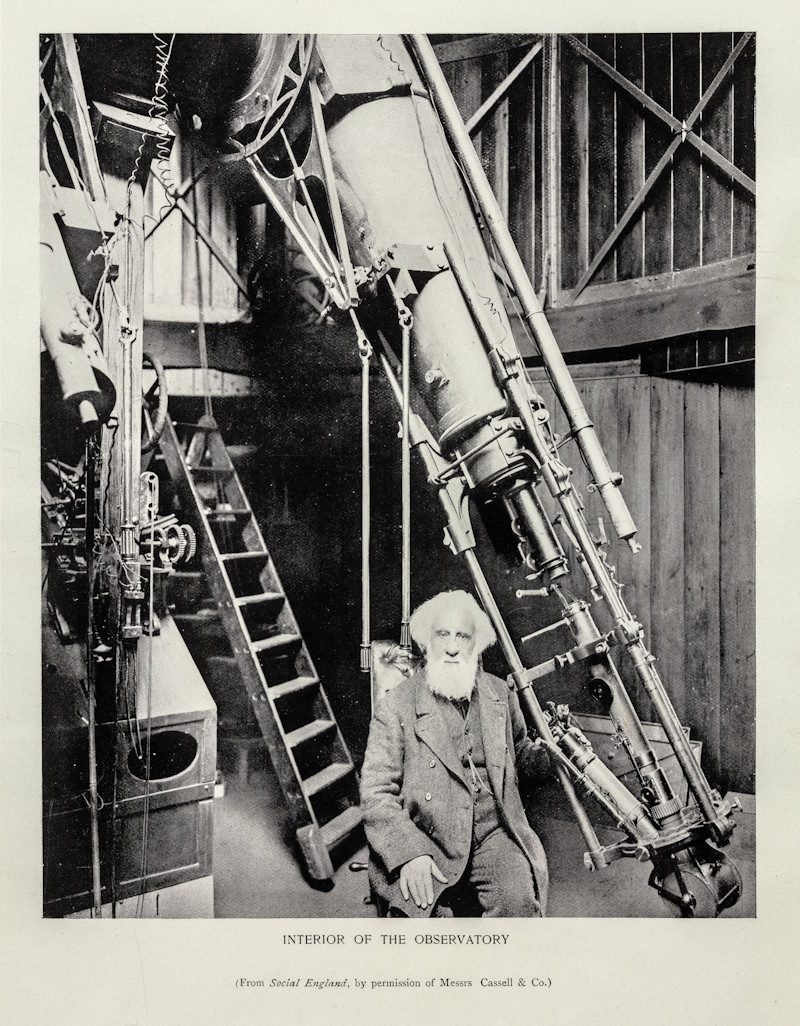

Despite all Margaret’s work, it took William 14 years after the start of their partnership to acknowledge her involvement, with their first co-authored paper (above) published in 1889. In this, he wrote: 'I have added the name of Mrs Huggins to the title of the paper, because she has not only assisted generally in the work, but has repeated independently the delicate observations made by eye.’ Despite ongoing research published in both names, her contribution also seems to have been downplayed in the collected papers of Sir William Huggins in 1909, the publication of which was funded by the Royal Society. I’ve already included two of the four frontispiece photographs in this blog showing Margaret, but it is perhaps with deliberate intent that the portrait of William shows him alone in the observatory with the Grubb telescope and not together with his collaborator.

William Huggins in the interior of the observatory at Tulse Hill, London (RS.21902). Frontispiece to The scientific papers of Sir William Huggins (1909)

William Huggins in the interior of the observatory at Tulse Hill, London (RS.21902). Frontispiece to The scientific papers of Sir William Huggins (1909)

Although this suggests that William was lukewarm in his scientific recognition of women, his decision to record Margaret’s contribution does at least speak of an affection for his wife. It’s also interesting to note that he included six illustrations by Margaret – one of which is reproduced below – in the publication of his 1906 book The Royal Society; or, Science in the state and in the schools. This celebrated her talents beyond science, and showed the support she gave to her husband and his work throughout their marriage.

A representation of scientific societies: illustration by Margaret Huggins featuring John Evelyn’s motto ‘Omnia explorate meliora retinete’ alongside the Society’s own ‘Nullius in Verba’

A representation of scientific societies: illustration by Margaret Huggins featuring John Evelyn’s motto ‘Omnia explorate meliora retinete’ alongside the Society’s own ‘Nullius in Verba’

I haven’t managed to establish what happened to the spectral instrument sent by Margaret Huggins, but if you’d like to see the earlier donation from Fraunhofer, alongside our copy of the 1899 Atlas of representative stella spectra by Margaret and William Huggins, then why not brighten your day by visiting our exhibition exploring the history of light and colour.