Women undoubtedly read and worked in the Royal Society library long before they became eligible for election to the Fellowship in 1945, as Louisiane Ferlier explains.

As we celebrate the 80th anniversary of the election of Kathleen Lonsdale and Marjory Stephenson, the first female Fellows of the Royal Society, I’m delighted to launch a series of blogposts looking back at the contribution of women to science.

Women’s access to the infrastructure of science was highly restricted in the nineteenth century. While science was becoming increasingly professional, women struggled to get through the doors of universities, laboratories, learned societies and other ‘scientific spaces’ well into the mid-twentieth century. And with entry to the Fellowship of the Royal Society barred to women until 1945, it would be quite logical to assume that entry to the Royal Society Library had been firmly shut to women beforehand.

In a 1995 article celebrating the 50th anniversary of women to the Fellowship, Joan Mason considered that the Ladies’ Soirées of 1876 marked the date when women were regularly invited to visit the Society (if only for a night). Yet, within the collections team, we were aware of suggestions that Mary Somerville had gained access to Royal Society Library books through her husband, William Somerville FRS, and of rumours that she even visited ‘out of hours’ in the 1830s and 40s.

Portrait of Mary Somerville by James Rannie Swinton, 1844, courtesy of Somerville College, University of Oxford, Creative Commons Licence

Portrait of Mary Somerville by James Rannie Swinton, 1844, courtesy of Somerville College, University of Oxford, Creative Commons Licence

The first suggestion is based on a passing comment by Mary Somerville’s daughter Martha in her fascinating biography of her mother, mentioning that William had spent time ‘searching the libraries for the books she required’. However, while a sculpture bust of Mary was displayed on the Society’s premises, her personal access to the Royal Society’s collections remains only a supposition. So as we mark the 80th anniversary of the election of Lonsdale and Stephenson, I’ve been sleuthing for proof that women did indeed use the Royal Society Library in the nineteenth century for their scientific pursuits.

Ada Lovelace explicitly requested access to the library through Mary Somerville’s son Woronzow Greig FRS. A letter held at the Bodleian Library shows how she asked Greig to plead with the Society’s secretary to give her entry in her husband’s name before opening time. In the absence of an answer from the Secretary, we can only hope that Ada Lovelace haunted our shelves in the early hours.

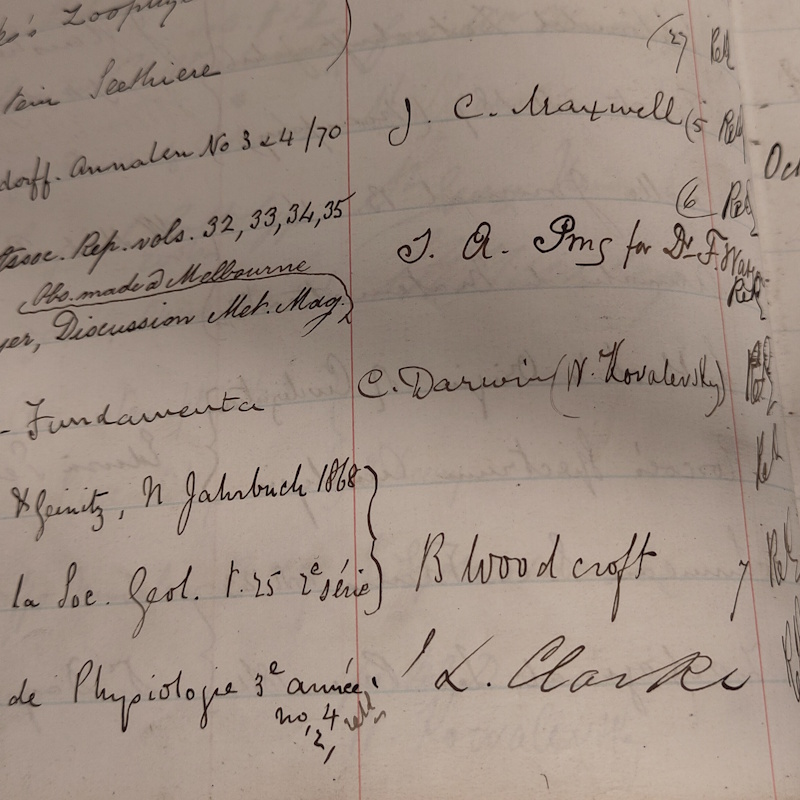

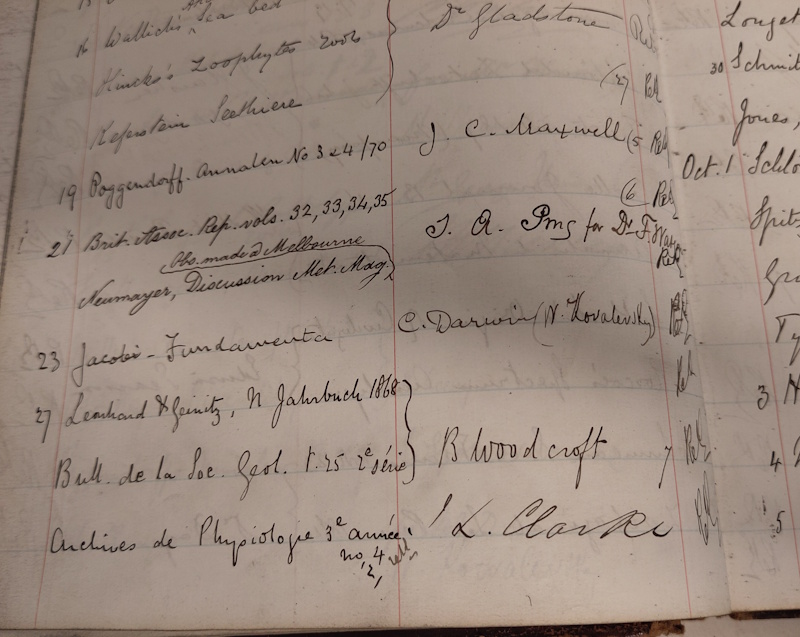

Charles Darwin borrowing a book on behalf of Sofia Kovalevskaya (lending book MS/401/4)

Charles Darwin borrowing a book on behalf of Sofia Kovalevskaya (lending book MS/401/4)

The lending books of the library have yielded more tangible proof, however. A letter from mathematician Sofya Kovalevskaya to Charles Darwin led me to an MS/401/4 entry by Darwin on 1 September 1870, noting that he was borrowing Jacobi’s Fundamenta nova theoriae Functionum ellipticarum. This was on behalf of what seems to me to be ‘W. Kovalevsky’, Sofya’s husband Vladimir (who signed his letters using a ‘W’, the German-style transliteration). It seems Darwin was reluctant to sign a volume out on behalf of a woman.

Portrait of Sofya Kovalevskaya, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Sofya Kovalevskaya, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

This proved that our books did reach women, but I was still lacking evidence of a woman in the library. Proof finally came when I was transcribing our lending book for 1853-1869, which was launched online on the day of our Libraries of Science conference. Entries in the lending book revealed that two women definitely visited the library: Grace Mary Percy and Phoebe Lankester.

Grace Percy, the wife of metallurgist John Percy FRS (who served as Royal Society Dining Club Treasurer during the period), borrowed five volumes of three periodical titles dedicated to chemistry: Erdmann’s Journal, Poggendorff’s Annalen, and Schweigger’s Journal. I could unearth very little information about Grace, and was rather dubious about concluding from the borrowing records that these were her loans, rather than books for her husband. He had conducted chemical analysis of metals and had borrowed similar titles under his own name previously.

More compelling evidence exists for Phoebe Lankester, a botanist, a prolific author of books and articles on British flora, and the wife of physiologist Edwin Lankester FRS, who had been elected to the Fellowship in 1845.

Portrait of Phoebe Lankester by Hubert von Herkomer, 1895. Courtesy of Colchester + Ipswich Museums: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

Portrait of Phoebe Lankester by Hubert von Herkomer, 1895. Courtesy of Colchester + Ipswich Museums: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

She borrowed four volumes, on the following dates:

5 November 1858: Thomas Pettigrew Medical portrait gallery, 1840 (RCN 50983)

8 December 1858: Engelbert Kaempfer The history of Japan, giving an account.... of its plants, 1727 (RCN 46507)

9 December 1861: Jean Jacques Rousseau Letters on botany addressed to a lady, 1791 (RCN 49928)

27 October 1862: Nouveaux Mémoires de l'Académie de Bruxelles, Tome 13, 1841 (RCN 6847)

Although the first of her borrowings overlaps more closely with her husband’s interests than hers, the remaining three were reference material for her own scientific pursuits. Kaempfer's History of Japan continues his botanical survey of the flora of Japan published in 1712, and includes his description of tea cultivation. It is also a rare first edition, in two very large volumes. Volume 13 of the Mémoires de l'Académie de Bruxelles includes an article by Belgian botanist Jean Kickx on the cryptogamic flora of Flanders.

Thomas Martyn’s translation into English of Rousseau’s Letters on botany addressed to a lady is, I would contend, the most significant of her borrowings. The volume is considered to be ‘a true pedagogical model’ in the teaching of botany, concentrating on the structure of plants and their order according to the Linnean system. It was meant to be read with a plant in hand, the same approach to botanical literature that Phoebe Lankester recommended.

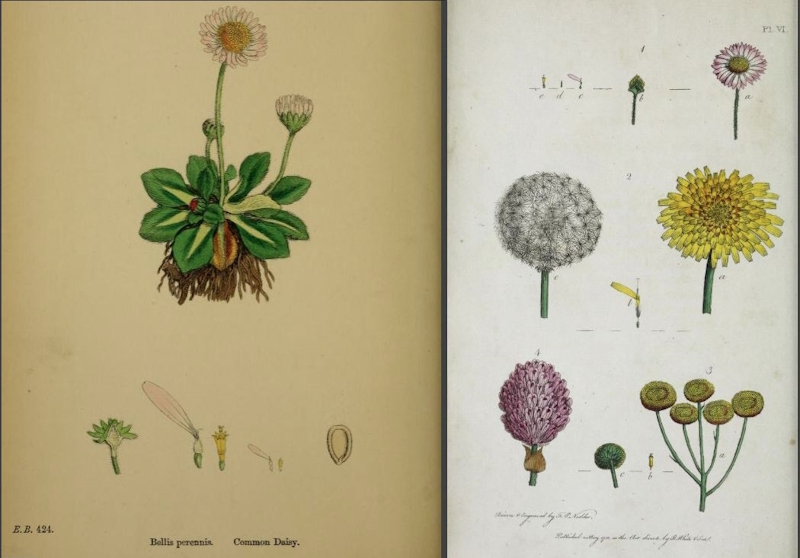

Left: Illustration of the daisy by John Sowerby in English botany, 1863; right: Illustration of Rousseau’s letter VI on compound flowers by Thomas Martyn, 1799.

Left: Illustration of the daisy by John Sowerby in English botany, 1863; right: Illustration of Rousseau’s letter VI on compound flowers by Thomas Martyn, 1799.

After much digging, I was delighted to find that she did refer to Rousseau’s volume at least once in her long and fascinating note on the daisy in volume 5 of English botany.

It’s also worth noting that Lankester shared her expertise on ferns with Marian Farquharson FLS FMS, the first woman to explicitly approach the Royal Society demanding clarification on women’s eligibility to the Fellowship. This was unfortunately rebuffed, but Farquharson’s quest for equality of admission to learned societies did find some success when the Linnean Society began to elect women in 1904, partly as a result of her campaign. Phoebe Lankester had earlier signed the 1866 petition requesting suffrage for women, and so it would be fascinating to find an archival connection between the two botanists and campaigners for women’s rights.

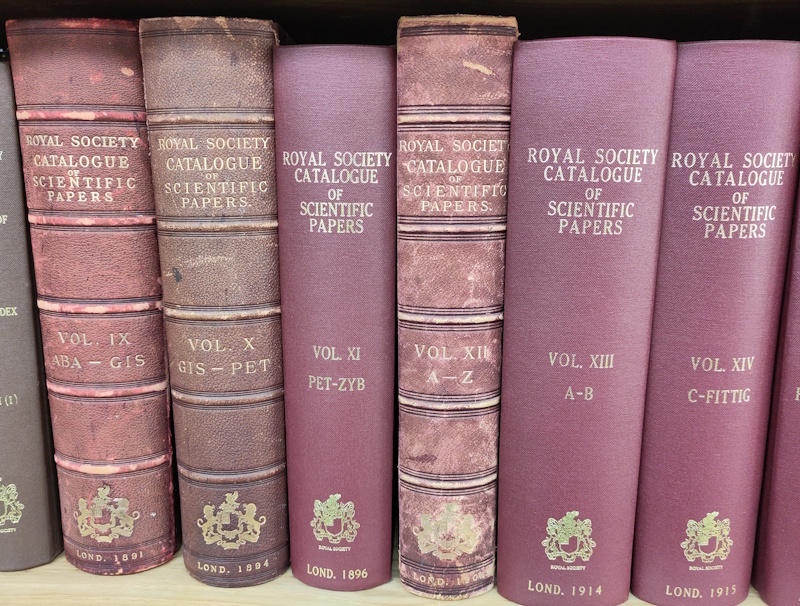

Before opening its doors (very slightly) to the scientifically-minded wives of its Fellows, the Royal Society Library had certainly received books by women and from women. And in terms of employing women, in 1890 the library recruited Miss Evelyn Chambers to head the ongoing ‘catalogue of scientific papers’ project, and in turn Chambers would bring in more female cataloguers. As the (male) Secretary of the Royal Society would be at pains to clarify to one of the candidates, however, this meant being employed in the Catalogue Department, not the library itself.

Nonetheless, as we’ve seen, women undoubtedly read and worked in the Royal Society library long before 1945, and I think it’s highly appropriate to celebrate their earlier interactions with our scientific collections as part of our 80th anniversary celebrations. Do keep an eye out for further articles on women’s contributions to science – we’ll be featuring Lady Margaret Huggins next week, then adding monthly posts until March 2026.