Louisiane Ferlier peruses the earliest books on navigation in the Royal Society’s collections.

Summer conjures images of lapping waves, the call of gulls and the saltiness of the sea, so let us set sail on the closest ocean. Rather than chasing mermaids as others have done before, I propose that we get ready by perusing the earliest books on navigation in the Royal Society’s collections.

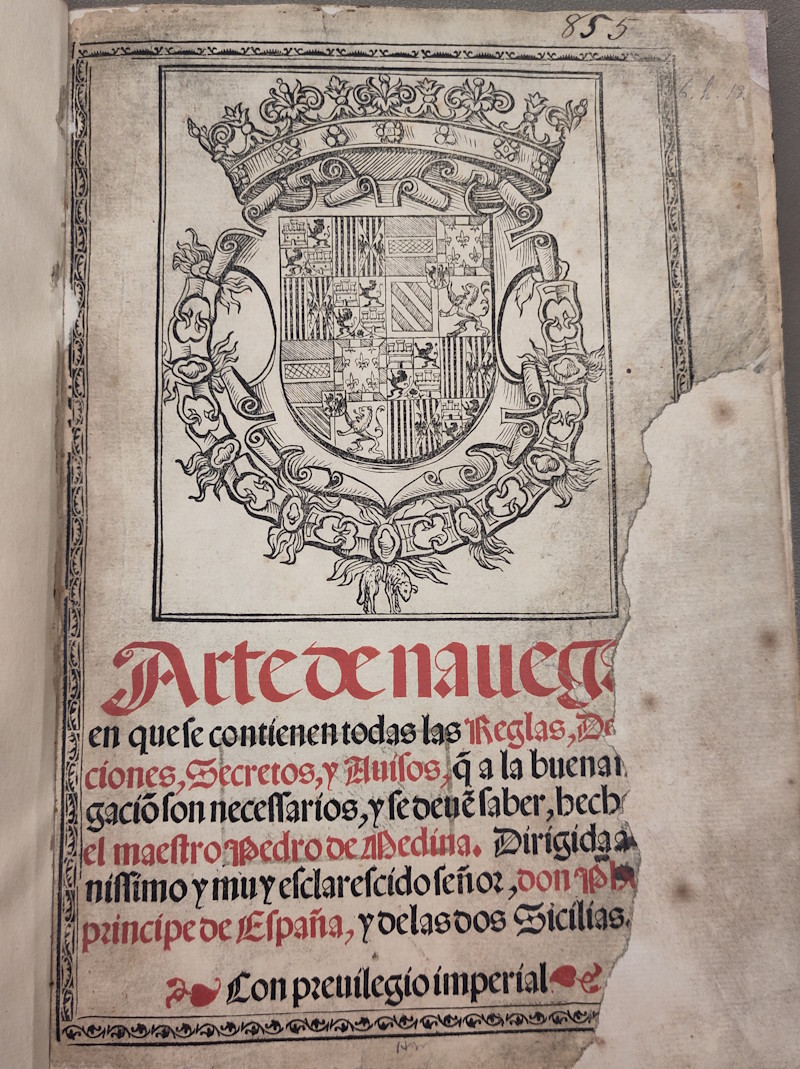

Our journey begins in 1545 in Valladolid, where Spanish cosmographer Pedro de Medina (1493-1567) published Arte de Navegar. The copy in our collections caught my eye because it is the earliest Spanish title in the Royal Society’s Library. The volume contains descriptions of instruments, maps and charts, with advice on how to use them.

Title page of the Royal Society’s copy of Arte de navegar, 1545

Title page of the Royal Society’s copy of Arte de navegar, 1545

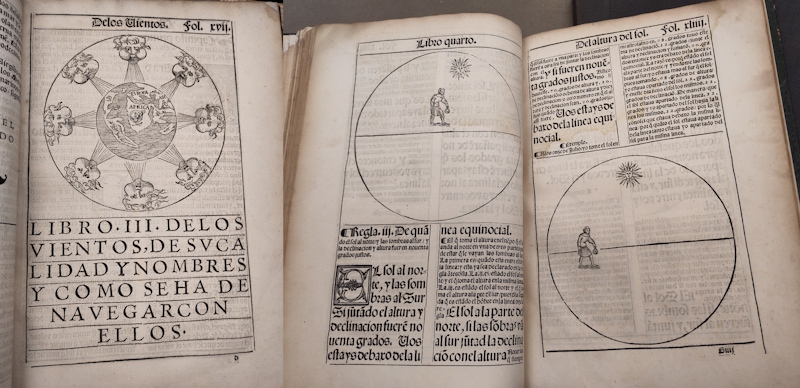

A careful compilation of theory and practice on tides, winds and the climate, drawn from a variety of sources, Medina’s volume opens with a description of the universe. The book cemented his reputation in the Spanish court and was translated into various languages to become a standard textbook around Europe.

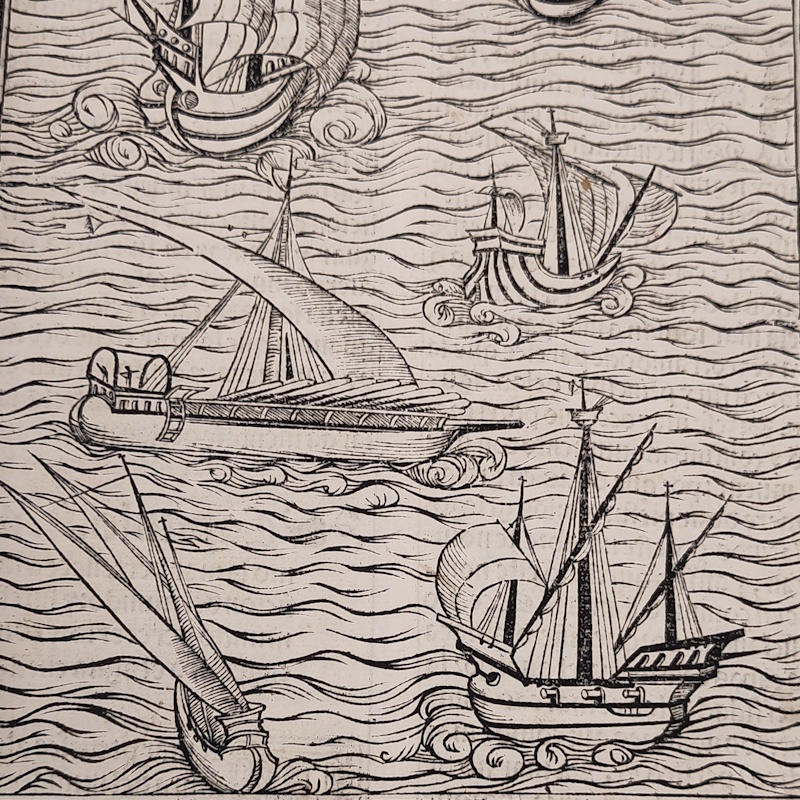

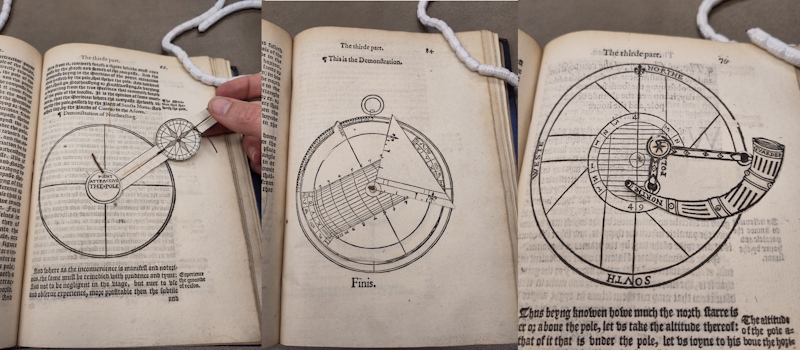

Woodcut illustrations from Arte de navegar

Woodcut illustrations from Arte de navegar

I assumed that The art of navigation (1561) was a translation of Medina’s treatise. It is, in fact, the English version of another influential Spanish navigational treatise, Brevé compendio de la sphera y de la art de navegar by Martín Cortés, originally printed in 1551. The art of navigation, which is proclaimed as the first treatise on the topic in English, is an amazing volume containing many paper models of navigational tools – here are a few pictures I took of our copy:

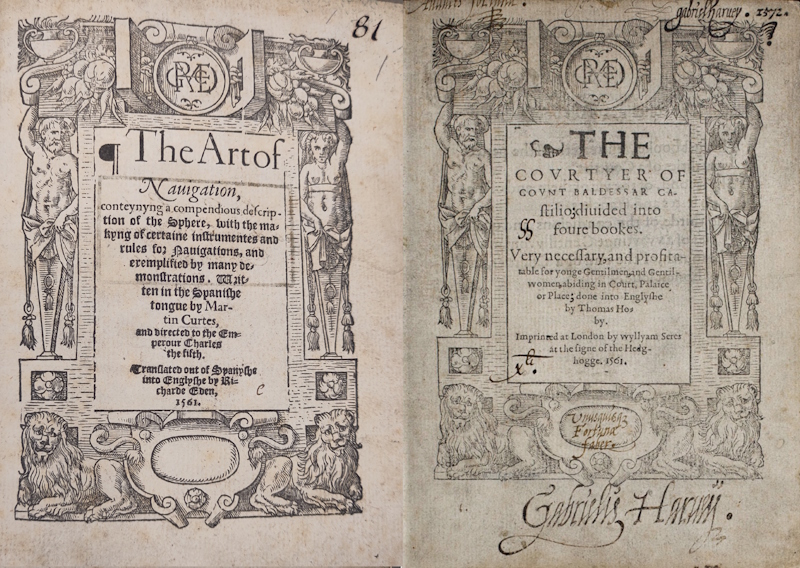

Translator Richard Eden (c.1520-1576) published the volume a mere ten years after the first Spanish edition, adapting its format and content for an English audience. The volume was printed by Richard Jugge* and John Cawood, the Queen’s printers, and I was particularly intrigued by the fact that the lavish woodcut on the title page was also used for the first English edition of Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the courtier printed by a competitor, William Seres, the same year.

Left: the Royal Society’s copy of The art of navigation, 1561; right: The courtyer of Count Baldessar Castiglio, 1561, Newberry Library, Special Collections, VAULT Case Y 712.C27495.

Left: the Royal Society’s copy of The art of navigation, 1561; right: The courtyer of Count Baldessar Castiglio, 1561, Newberry Library, Special Collections, VAULT Case Y 712.C27495.

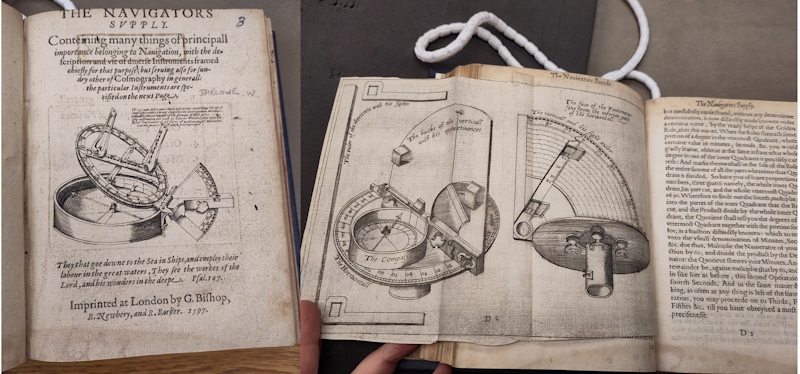

We care for quite a few other sixteenth-century books of navigation, such as The navigators supply (1597) by William Barlow, which includes foldout plates describing a pantometer long before the supposed invention of the instrument (which combines a compass and ruler on a disc to enable easy triangulation) by Athanasius Kircher.

William Barlow, The Navigators supply (1597), in the Royal Society Library

William Barlow, The Navigators supply (1597), in the Royal Society Library

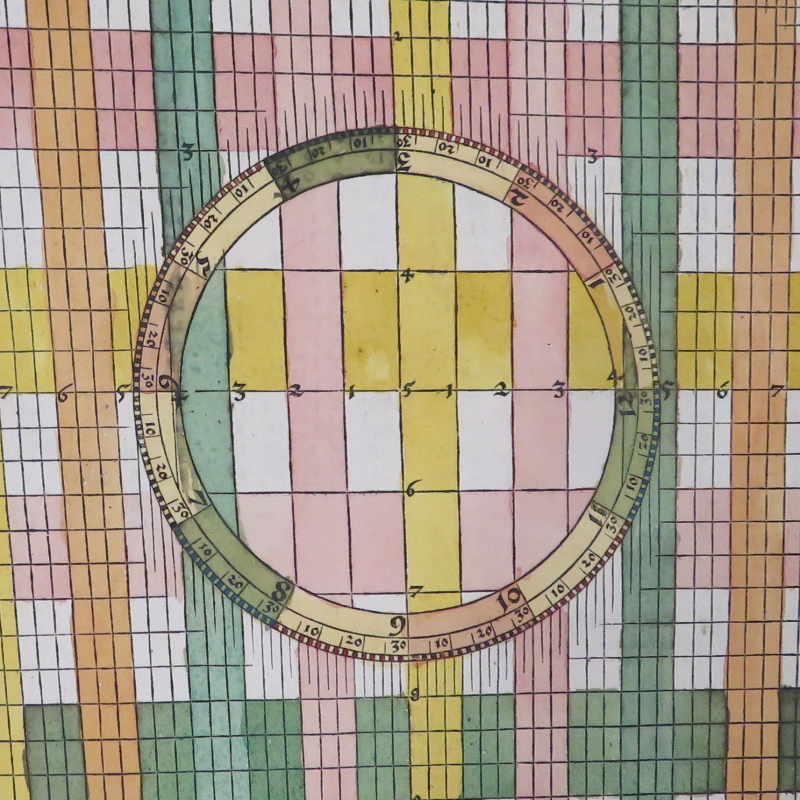

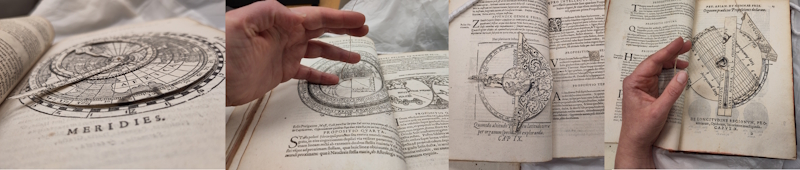

Our journey must end, though, on the pages of my favourite instrument-book, a 1584 edition of the Cosmography of German humanist Peter Apian (1495-1552) expanded by Dutch cartographer Gemma Frisius (1508-1555). The volume is a significant compendium of knowledge on our world and its position in the universe, its many volvelles inviting readers to interact with it by calculating their own individual positions.

The volvelles and paper instruments in the Royal Society copy are in wonderful condition for delicate 430-year-old contraptions of string and paper. This is because the paper was reinforced throughout by pasting left-over printed papers – here’s the back of a volvelle page with decorative reinforcement:

It’s worth noting that I found no evidence that any of our authors ever actually went to sea. Although they were marketed as tools for mariners, these paper instruments were essential for astronomers, mathematicians and surveyors and were a display of technical prowess on the part of the printers and engravers.

I’d relish the challenge of digitising one of these volumes for our Turning the Pages resource, after our successful completion of the medical flapbook, so it may be that I return to these volvelles. In the meantime, Boris Jardine has made a study of paper instruments, and I highly recommend any of his articles for anyone interested in reading more. For my part, though I’m absolutely fascinated by the role of paper in diffusing the science and art of navigation, I’m not sure I’d trust any mariner trained only from the comfort of their armchair. Sail on!

* Richard Jugge is credited as the inventor of the printed footnote.