Who is the earliest female author on the shelves of the Royal Society Library? Rupert Baker investigates...

I hope you’ve been enjoying our recent flurry of articles on the history of women in STEM, prompted by the 80th anniversary of the election of the first female Fellows of the Royal Society. Several have focused on the interaction of women with the Society pre-1945, from Elizabeth Fulhame and Mary Senex to Mary Somerville and Phoebe Lankester.

Those of you with longer memories may also recall my piece on the earliest printed book in our collections. Pulling these two research strands together, I thought I’d look at where this particular Venn diagram intersects: who’s the earliest female author on the shelves of the Royal Society Library?

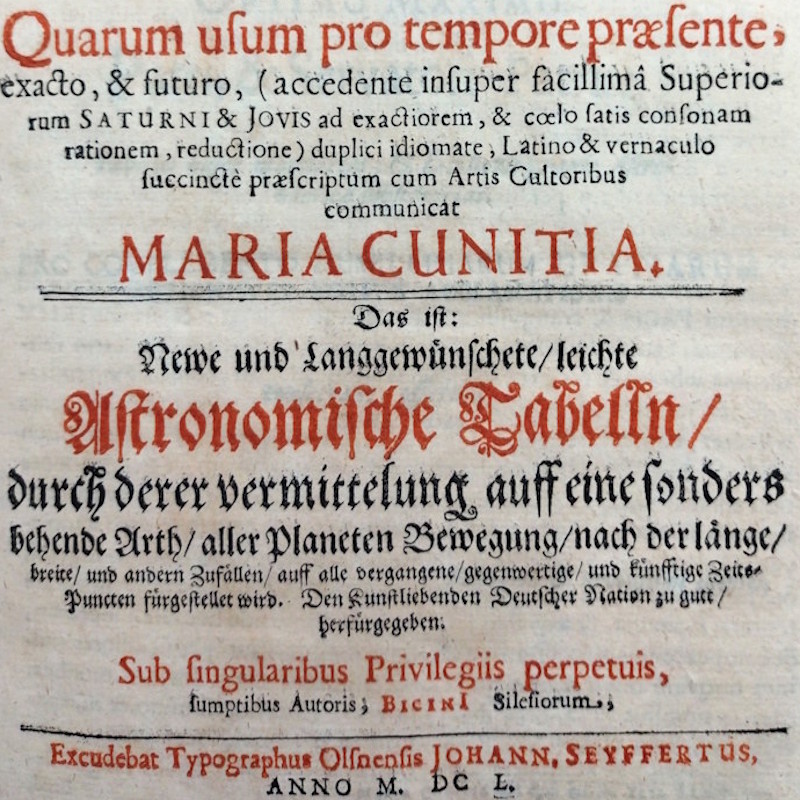

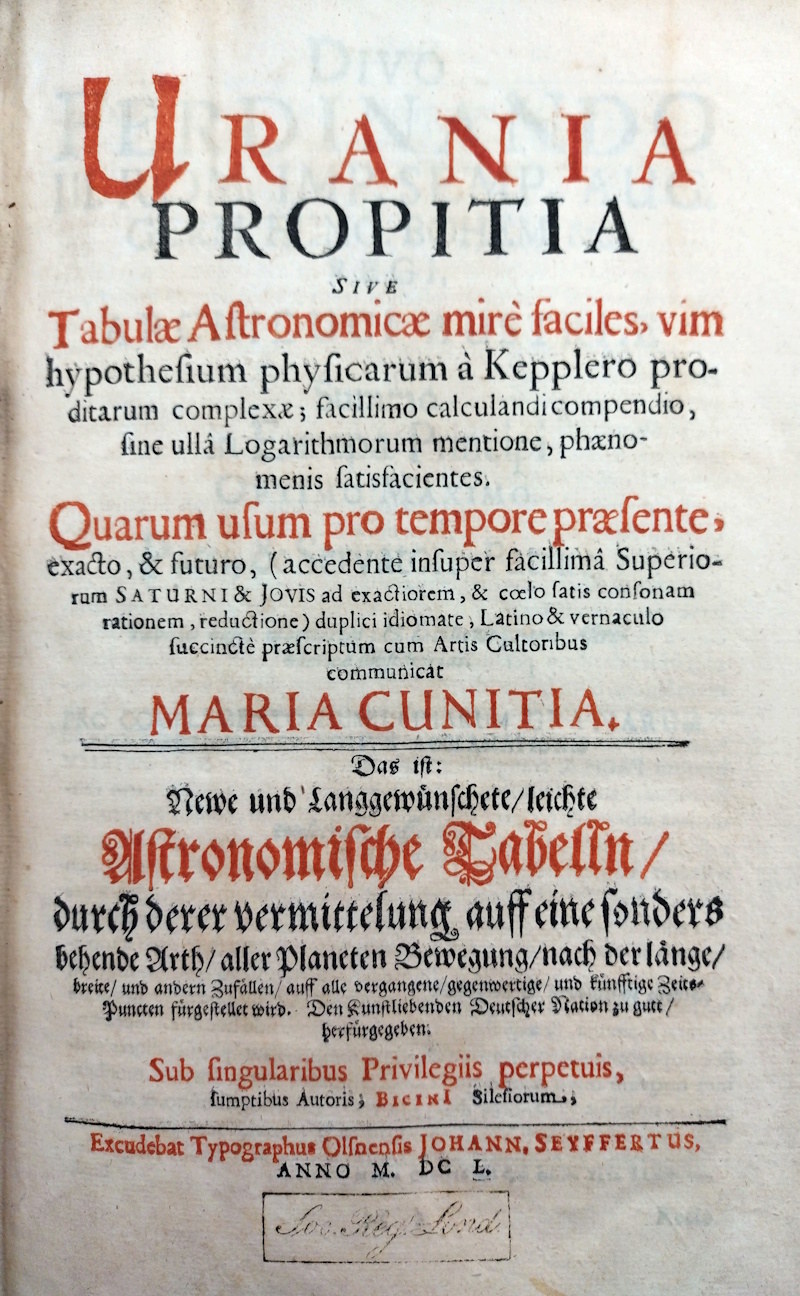

A prime suspect might be Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, back in May 1667. Her earliest books came out in the 1650s, but the only one in our holdings – a second edition of Grounds of natural philosophy – was published in 1668. This puts Margaret Cavendish in second place, eighteen years behind our winner: Maria Cunitz, with her 1650 book of astronomical tables, Urania propitia. Here’s the title page of our Library copy:

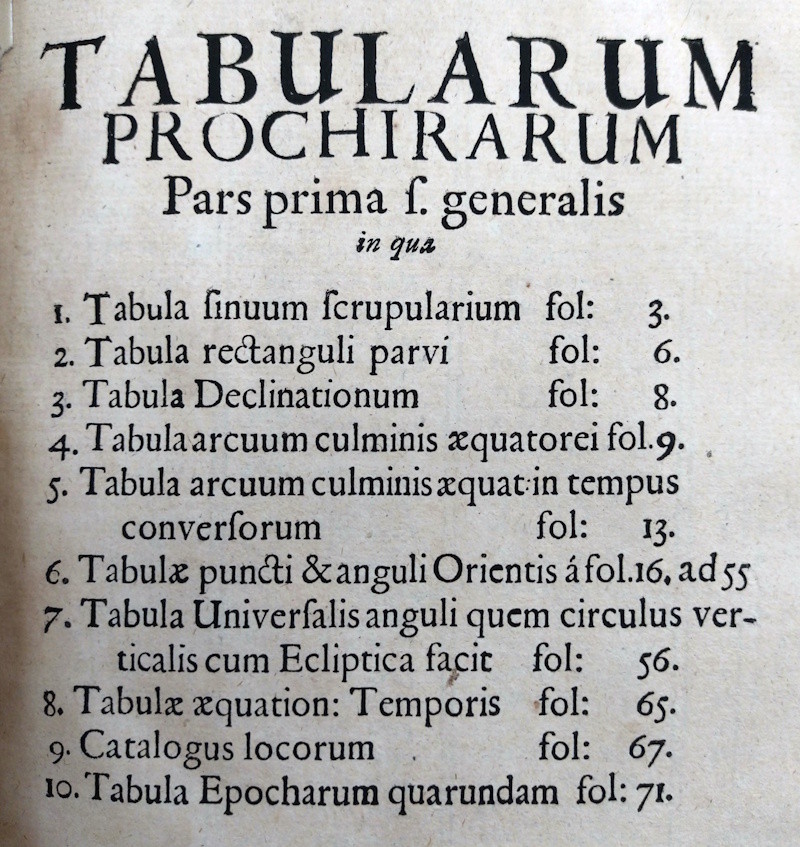

If your Latin is as patchy as mine, you might appreciate a (machine) translation of the first bit of that lengthy title: it comes out as ‘The kindly Urania, or wonderfully easy astronomical tables, revealing the power of complex physical hypotheses put forth by Kepler’. The book, written in both Latin and German and namechecking the Greek muse of astronomy in its title, is an attempt to simplify and correct Johannes Kepler’s 1627 Rudolphine tables, making the computation of planetary positions more straightforward for seventeenth-century astronomers and astrologers, without the need for Kepler’s complicated logarithmic methods. It includes tables for spherical astronomy, the orbital motions of the planets and the moons of Jupiter, and the computation of eclipses, together with a catalogue of the fixed stars. The contents list of one section looks like this:

The author, Maria Cunitz, is a fascinating figure. Born around 1610 in the clothmaking town of Wohlau in Silesia (modern-day Wołów, in south-east Poland), she was barred as a woman from attending university, and was instead taught mathematics and medicine by her father, a physician. Her studies in astronomy were encouraged by her second husband, who put her in contact with notable astronomers of the period, including Royal Society Fellows Ismael Bullialdus and Johannes Hevelius. Unsurprisingly, no portrait of Maria exists, but she’s commemorated by a statue in the Polish town of Świdnica, where she grew up – note the copy of Urania propitia clutched in her right hand:

Credit: Sueroski, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Her book was highly regarded in its day for its command of astronomical theory and computational rigour, and copies are known to have reached the Royal Observatory in Greenwich via John Flamsteed, and the University of St Andrews courtesy of James Gregory. However, as the work was privately printed at Maria’s expense at a press in the small town of Oleśnica, it was always a scarce item. Maybe not quite as rare as the ‘nine remaining physical copies’ quoted in its Wikipedia entry would suggest; I’ve been in contact with a historian of science who has ‘verified the existence of between 26 and 28 copies, and I suspect there may be more in Eastern European countries that haven't yet got into the catalogues I have searched’. Still desirable enough, however, to sell for £32,500 (against an estimate of £7,000 – £9,000) at Sotheby’s in September 2018, the most recent example I could find of a copy coming to auction.

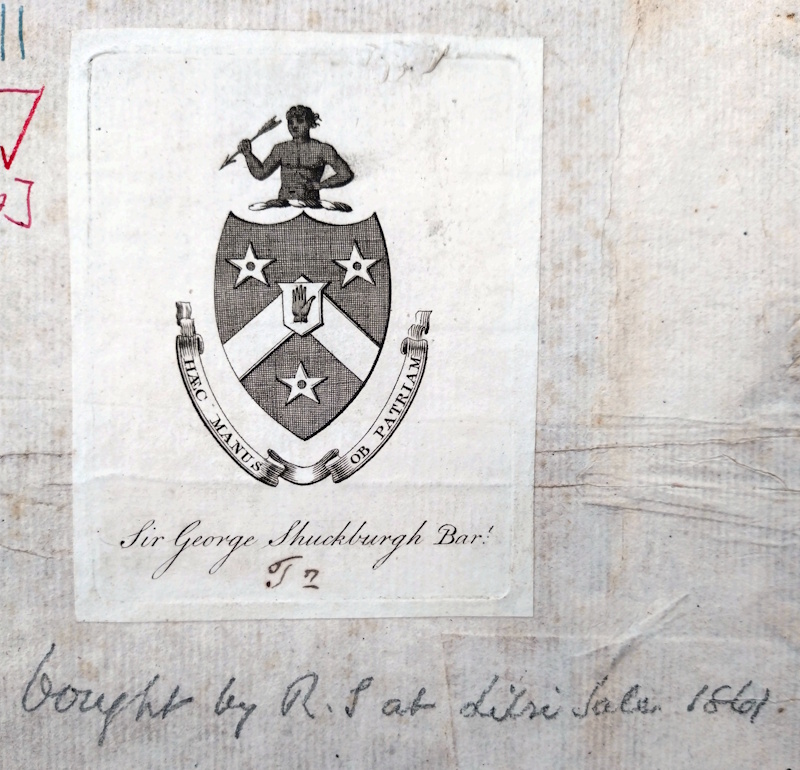

The provenance of our copy is interesting, too. The front pastedown (above) features the armorial bookplate of the mathematician and astronomer Sir George Shuckburgh FRS (1751-1804). Below that is the pencil inscription ‘bought by R.S at Libri Sale 1861’, referring to the auction on 25 April of that year, also at Sotheby’s, of ‘The mathematical, historical, bibliographical and miscellaneous portion of the celebrated library of M. Guglielmo Libri’. There’s an online version of the auction catalogue here, and Urania propitia (‘now very scarce’) is lot 2016 on page 234.

It's unclear how the book passed from Shuckburgh’s collection to that of the Italian mathematician and bibliophile Count Guglielmo Libri; given the latter’s often nefarious acquisition policy, it might be best not to ask. Frustratingly, there are gaps in the Royal Society’s financial record-keeping in the mid-nineteenth century, and I’ve not been able to trace how much we paid for Urania propitia, or whether we purchased any other books at the same auction. The minutes of the Library Committee contain several entries which read ‘Certain books were ordered for the Library’ – drat those nineteenth-century librarians, couldn’t they have taken my approach and compiled an acquisitions list on an Excel spreadsheet?

If further information turns up regarding our purchase or the book’s previous owners, I shall report back. Meanwhile, Urania propitia is going on my conservation binding list, as the front board and endpapers are detached and it could generally do with a little TLC. I’m very pleased we have a copy in our collections, though, imperfect or not – it has been described by historian of science Noel Swerdlow as ‘the earliest surviving scientific work by a woman on the highest technical level of its age’, and is another significant reminder of the contribution of women to science over the centuries.