Rupert Baker visits the Royal Gunpowder Mills and discovers historical links to several Fellows of the Royal Society.

A recent family excursion saw us make the short journey up the A10 from Enfield to Waltham Abbey, home of the Royal Gunpowder Mills.

Great fun was had watching the explosive displays on the Test Range, and a variety of scientific experiments in the Mad Lab (including a particularly fine Mentos and Diet Coke fountain). There was plenty of brain food for the grown-ups too – while our boys were applying themselves to ice creams in the spring sunshine, I popped into the excellent history exhibition. I suspected I’d find a few Fellows of the Royal Society (Fellow-spotting gets to be a bit of a habit when you’re out and about, as you may remember from this earlier post), and I wasn’t disappointed: a couple of names I recognised instantly, and two more I’d vaguely heard of and jotted down for later research, away from the noise of explosions.

Gunpowder production in this peaceful part of Essex began in the 1660s, when an existing mill was converted to manufacture gunpowder during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The choice of location proved successful, as it combined proximity to a water supply (the River Lea and a network of canals added over the years), local alder and willow woodlands to produce charcoal, and a nearby works for manufacturing saltpetre (charcoal and saltpetre, along with sulphur, being the components of gunpowder).

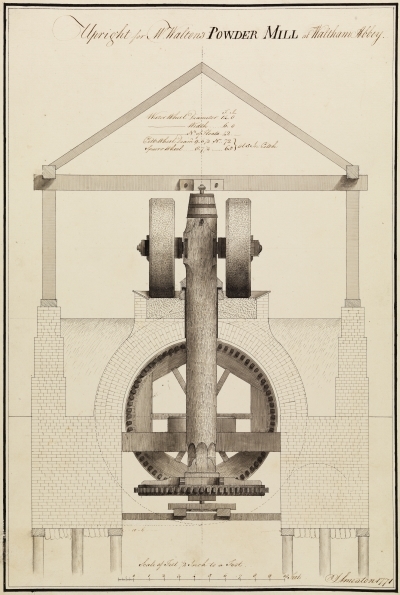

Owned by the Walton family for almost a hundred years, the site saw expansion in the 1770s with the construction of new mills, and here’s where the first of our Fellows comes on the scene: the civil engineer John Smeaton. Now, this was a name that brought an instant flash of recognition, not least because I suspect my arms have been stretched a couple of inches over the years through carrying weighty volumes of our Smeaton Drawings into the Library for readers. The drawings are a rich resource for historians, and one we’ve been digitising for our Picture Library – type ‘Smeaton’ into the search box to see images of his Eddystone Lighthouse, Forth Canal locks and beer cisterns, as well as two of his 1771 designs for the new powder mills at Waltham Abbey, one of which is shown here:

Sectional elevation for the water-driven powder mill at Waltham Abbey, by John Smeaton, 1771 (JS/2/38v © The Royal Society).

The site was purchased from the Walton family by the Crown in 1787, and developed as a state centre of excellence for gunpowder experimentation and production. This was largely on the advice of William Congreve, then Superintendent of Military Machines at the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich – his name rang a vague bell with me and he did, on subsequent investigation, turn out to be an FRS. There are three letters in our Miscellaneous Manuscripts (MM) archival collection in which Congreve writes to the Board of Ordnance in 1801 on plans ‘for erecting Powder Works near Waltham Abbey’, expressing his concerns that the traverse blast walls in the contractors’ plans would prove insufficient to prevent an explosion from destroying surrounding buildings.

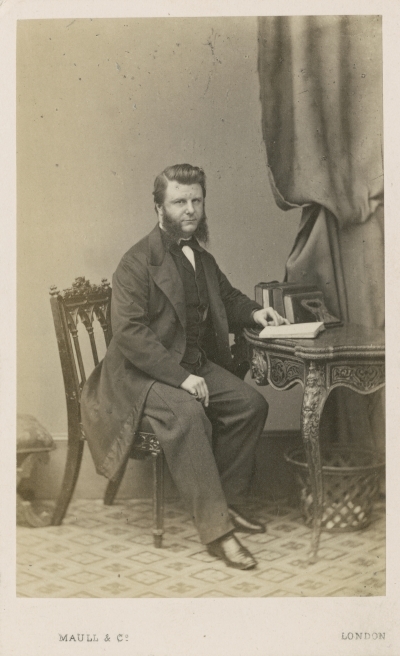

Further development at the Waltham Abbey Mills was stimulated by the Napoleonic and Crimean Wars, and the advances in gunpowder technology also had civilian spin-offs which improved quarrying, canal tunnelling and railway building. Then, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, other explosives with advantages over gunpowder were developed at the Mills – in 1865 a patent was granted for guncotton (nitrocellulose), with its greatly increased blasting power, and in 1889 the spaghetti-shaped smokeless propellant cordite was patented. The key name here is another of our Fellows, Frederick Abel, who also features prominently in the history display at Waltham Abbey. I looked him up in our archive catalogue and found several intriguing references to a dispute between Abel and the German chemist Herbert Sprengel over the properties of wet guncotton, both in MM/16 and in the New Letter Books. We also have several photographs of Abel in our picture collection, including the extravagantly-muttonchopped example below – a late contender for the ‘best scientific whiskers’ award suggested in a previous post?

Studio portrait of Frederick Abel FRS by Maull & Co., ca. 1875 (image RS.7725 © The Royal Society).

As you’d expect, the Waltham Abbey site played a key role in explosive production during the Great War (the social history of the huge number of women working at the Mills is a fascinating story in itself) and in World War Two, even as production was gradually transferred to the west of England, further from Luftwaffe bombers. One final FRS features in the story here: as the sole production facility for the explosive RDX, the Mills provided a key component for the bouncing bomb developed by Barnes Wallis.

The Royal Gunpowder Mills closed just after WWII, but the site was transferred immediately to the new Explosives Research and Development Establishment, producing rocket motors and propellants for the Skylark and other UK rockets. Finally shutting down as a research establishment in 1991, parts of the site were decontaminated, designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest and opened to the public … which is where our family trip comes in.

Gunpowder press, blast wall (under scaffolding) and water wheel. Author’s photograph, April 2015.

It’s a haunting experience to walk away from the visitor centre and head north along the Woodlands Nature Walk, passing crumbling canal banks and railway lines, huge blast walls overgrown with grass, water mills and ‘press houses’ for gunpowder production. To this film buff, it was eerily reminiscent of the Zone in Tarkovsky’s Stalker, deep in the woods with birdsong and the breeze through the trees as the only soundtrack. Well, that and the plaintive cries of ‘Dad, can we have another ice-cream, and fire the tennis-ball cannon again?’ At which point we headed back to the crowds – loud bangs are fun, too. One final tip if you’re planning a visit (which I definitely recommend): when the explosive technicians at the Test Range tell you that it might be a good idea to cover your ears, do exactly as they suggest…