One of the most important things when creating any digital collection is to think about search, findability, and access of the digital materials.

One of the most important things when creating any digital collection is to think about search, findability, and access of the digital materials. There is little point in digitising material, indexing it, and putting it online if the right people can’t find what they’re looking for.

When thinking about how to describe the contents of a collection, the most important factor to determine is who the users will be. Are they likely to be scholars and historians? High school or university students? Members of the general public who are interested in science? Thinking about who is going to be using a collection is the first step to determine how to describe it.

Search and our journal collection

Search is reliant on descriptive metadata – the information added to content to ensure people who are looking for a specific item can find it. For the Royal Society Journal Digitisation project, this was a very important part of our job – and quite a complicated one.

One of the core aims of this project is to increase the interest in and understanding of science worldwide, at all levels of interest and expertise. Therefore, every article has been indexed individually by experienced indexers who have captured a wealth of information that was not previously searchable.

This includes:

- Contributors, such as authors, communicators, illustrators and observers

- Article types, such as observations, experiments, letters or abstracts

- Relevant dates and places composed, received by the Royal Society, revised and/or read to the Society

These metadata are captured using easily recognized terms and, when online, will be fully searchable. This means that anyone, whether they’ve used the Society’s collections extensively or are first time users, should be able to find what they are looking for, and expand or narrow their search accordingly.

Terms over time in Royal Society journals

Beyond just capturing information that is present in each article, we had some more complex problems to think about, especially when thinking about how to describe things. A very common search tool used in online collections of all kinds is the use of subject headings and keywords; these are the tags that describe the thing you’re looking for.

For example, if you were looking to find articles related to Captain Scott’s Discovery polar expedition, you might use keywords such as “expedition” and/or “Antarctica”. This is simple enough for the more modern articles, and should hopefully get you good search results, but it’s not always so simple. While some subject headings would seem to be obvious, i.e. “science”, “physics”, “Newton, Isaac, 1642-1727”, or “biology”, it would be very easy for them to be inappropriately applied, such as having every article in the entire collection being tagged with the “science” subject heading; that would be a lot of results to sift through! The decision was taken that we would rather not have a heading than have an incorrect one, or one that is unhelpful.

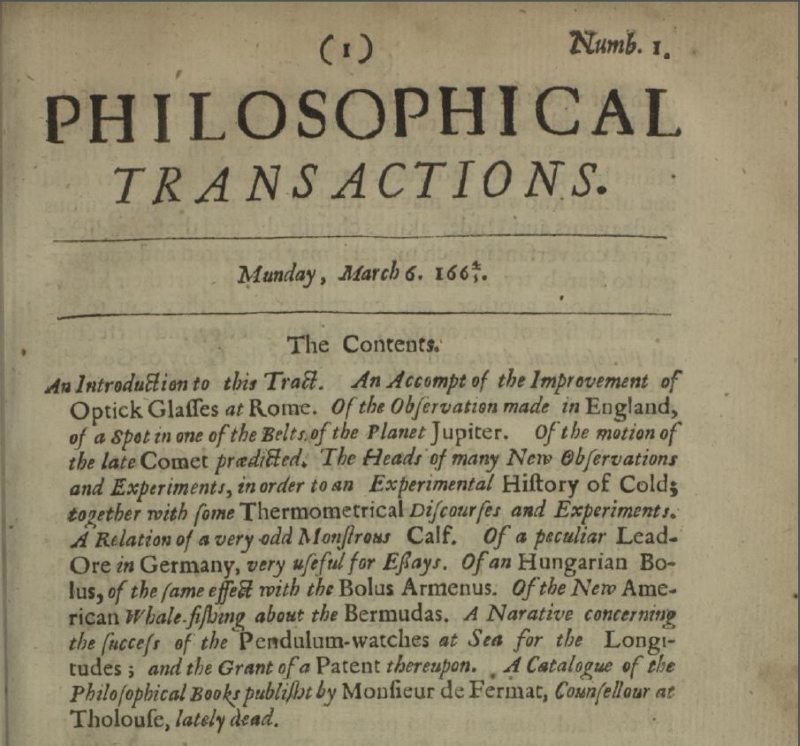

And it gets even more complicated when looking for older materials. The Royal Society Journal Collection spans almost 350 years, and there have been many changes to accepted terms, spelling, and scientific categories in that time. For example, what was once referred to as the “mechanism of the heavens” would now be called simply “astronomy”. Even the name of the first journal, the “Philosophical Transactions”, refers to the study of “natural philosophy”, but would now more likely be referred to as the “Scientific exchanges”. The use of the long “s” looks more like an “f” to modern readers, and could also be confusing. We had to decide: do we use current practices, even if the original authors would not have understood them, or do we use those that the original authors themselves would have used, even if they are no longer accurate or recognizable today? Which would return greater search results and be more beneficial to more users? As the aim of the project is to increase the understanding of science and its reach worldwide, this could be problematic. This problem has yet to be resolved, but we are contemplating the use of crowdsourcing or automated extraction as possible solutions.

What do you think?

Should we have used the historic search terms or the more modern ones in use today? Can you think of other ways to get the right results?