Rupert Baker discovers the stories behind a plaque to Sir John Charles Bucknill FRS in Northernhay Gardens, Exeter.

As I mentioned in a blog post many moons ago, I’m always on the lookout for the letters ‘FRS’ on plaques, plinths and statues when I’m rambling around.

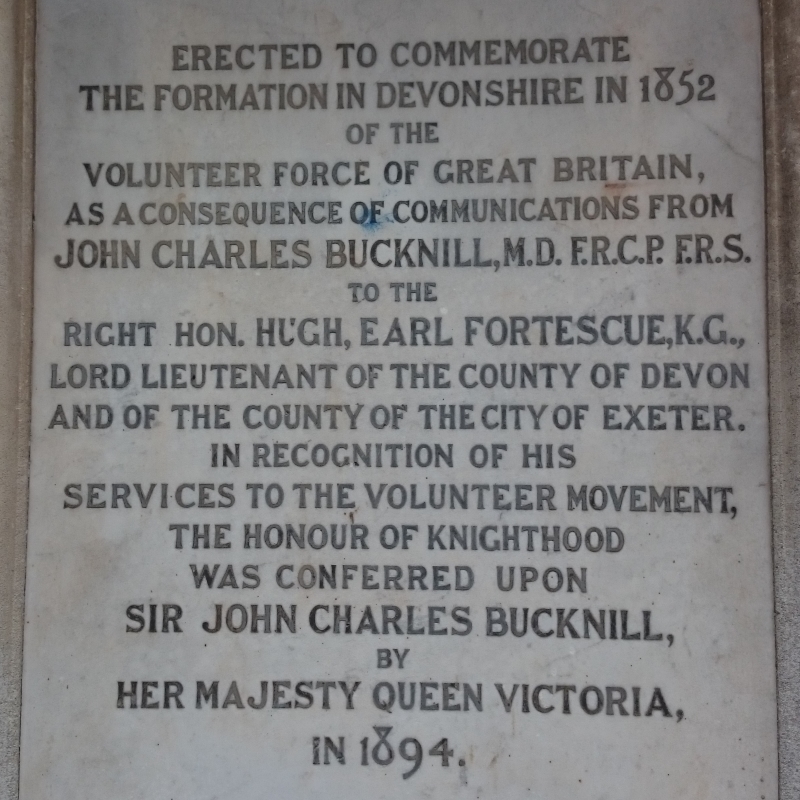

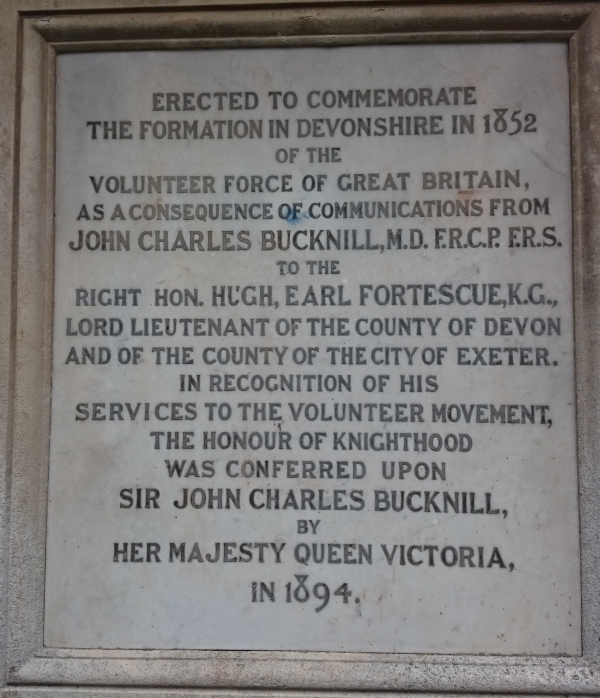

I’m not sure that spotting the name of an obscure Fellow and feeling an immediate need to find information about them counts as a classic Pavlovian reaction – you know, the thing with bells and salivating dogs* – but it’s certainly ingrained in my brain at some deep level. So when I visited Exeter recently to show the family my old university haunts, an inscription on a plaque in the lovely Northernhay Gardens caught my eye:

So, who was Sir John Charles Bucknill (I’d never come across him before), how did he acquire all those letters after his name, and what was the Volunteer Force of Great Britain?

Born in 1817 and educated at UCL – which would make him one of the earliest students at London’s first university – Bucknill qualified as a doctor in 1840. His Devon connections began in 1844 when he took up the role of medical superintendent at the new County Asylum in the village of Exminster, a post he was to hold for 18 years. Looking again at the inscription in the photo, this ties in with Bucknill’s ‘communications … to the Right Hon. Hugh, Earl Fortescue, K.G., Lord Lieutenant of the County of Devon’ and the subsequent formation of the Exeter and South Devon Volunteer Force in 1852, with Bucknill as the first recruit to be sworn in.

The Volunteer Force movement seems to have fully taken off in 1859, prompted by fears that the army was overstretched by its role in maintaining the British Empire and would be insufficient to resist a threatened French invasion. As the Devon branch (by then the 1st Devonshire Rifle Volunteers) had already been in existence for several years, thanks to Bucknill’s promptings, it became one of the two senior rifle corps in the new movement. We can therefore say that a Royal Society Fellow was a prime mover behind an important defence initiative, which became part of the wider Territorial Force in 1908, then later morphed into the Territorial Army and its current incarnation, the Army Reserve.

Meanwhile, Bucknill’s medical career appears to have flourished in Devon, where he gained a reputation for his humane and enlightened views on the treatment of insanity. The 1850s saw the publication of two monographs on the subject, ‘Unsoundness of mind in relation to criminal acts’ (1854) and ‘A manual of psychological medicine’ (1858), followed by a couple of intriguing diversions into the life of the Bard: ‘The psychology of Shakespeare’ (1859) and ‘The medical knowledge of Shakespeare’ (1860); editions of all these works can be found on our Library shelves.

The ‘F.R.C.P.’ on Bucknill’s plaque refers to his election as a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1859, and seven years later he became a Fellow of the Royal Society, with his election certificate noting that he held the wonderfully Dickensian post of ‘Chancery Visitor of Lunatics’. A fact-finding trip to the United States in 1875 led to a fresh round of publications, including ‘Notes on asylums for the insane in America’ (1876) and ‘Habitual drunkenness and insane drunkards’ (1878). The last years of Bucknill’s life were split between private practice in London and – another string to the bow of this industrious Victorian – the cultivation of ‘a considerable acreage’ of farmland in Warwickshire; he was also a Freemason and keen sportsman.

The final date on Bucknill’s plaque refers to the knighthood awarded by Queen Victoria in 1894 for his services to the volunteer movement. The single photograph of Bucknill in our picture collections must date from around the time of his knighthood as it shows him at an advanced age; it also elevates him instantly to the top rank in our Best Scientific Whiskers pantheon:

Local Heroes’ scheme later this year.

* According to the opening sentence of a recent Pavlov biography which I’ve just acquired for the Library, this never happened anyway. Whatever next – no falling apple in Newton’s orchard?

N.B. If you’re struggling to place the title of this post, it’s from Richard III Act V Scene 3. And no, I didn’t know that off by heart, I found it on Wikiquote…