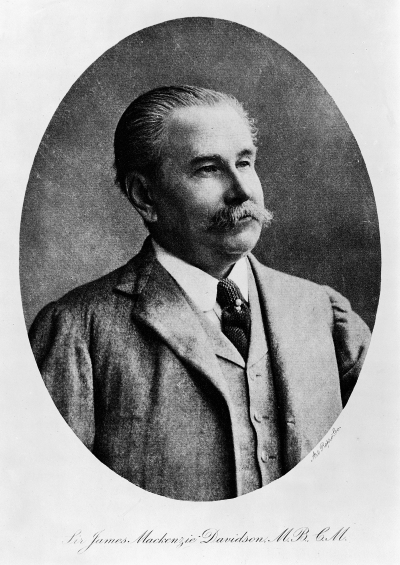

Ellen Embleton catalogues some newly-acquired papers and correspondence of James Mackenzie Davidson, a treasure trove of information on the early days of radiography and X-rays.

When Wilhelm Röntgen discovered the new ‘X-ray’ in 1895, James Mackenzie Davidson was quick to realise the opportunities that it afforded. From that point onwards, he devoted his career to promoting the application of X-rays to practical medicine. A collection of some of Mackenzie Davidson’s correspondence and papers has recently been accessioned here at the Royal Society, and it provides a unique insight into his success in this undertaking. It also illuminates some of the central discussions that were taking place around radiography when, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was still a relatively new science.

It became increasingly clear to me, as I catalogued my way through this fascinating collection, that Mackenzie Davidson was especially known for his method of localising foreign bodies and his development of stereoscopic radiography, both of which were used extensively throughout World War I to locate shrapnel in wounded soldiers. Though aware of the value of X-ray photographs (or ‘skiagraphs’ as they are often referred to within the collection), Mackenzie Davidson noted that they could ‘tell us little more than that a foreign body was present’ somewhere within a patient. Unsatisfied, Mackenzie Davidson devised apparatus that could localise the point on the skin that the foreign body lay below and could provide a stereoscopic impression of its depth below the skin, allowing for greater accuracy in removal.

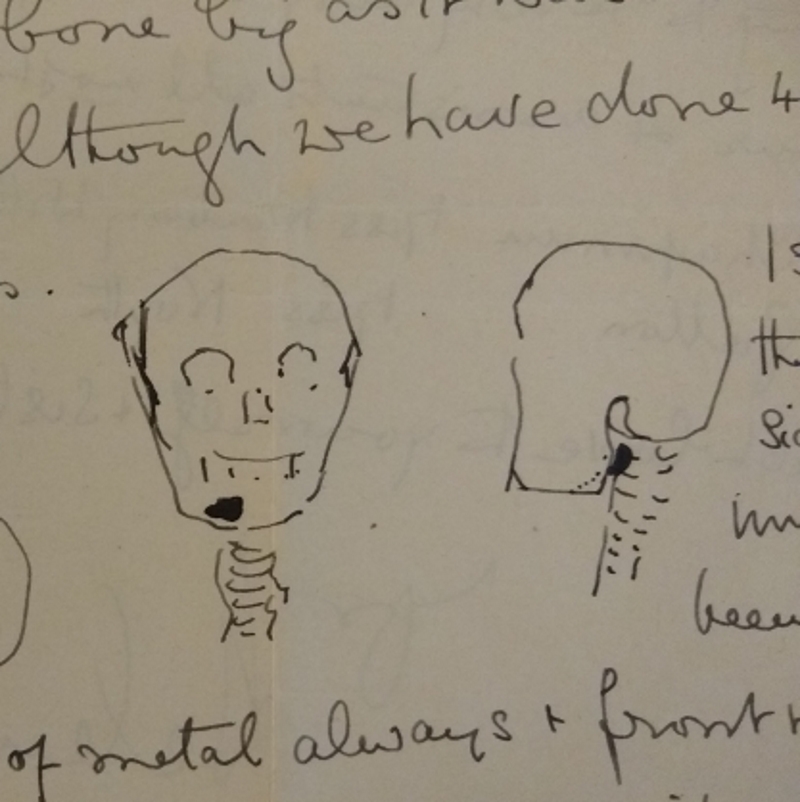

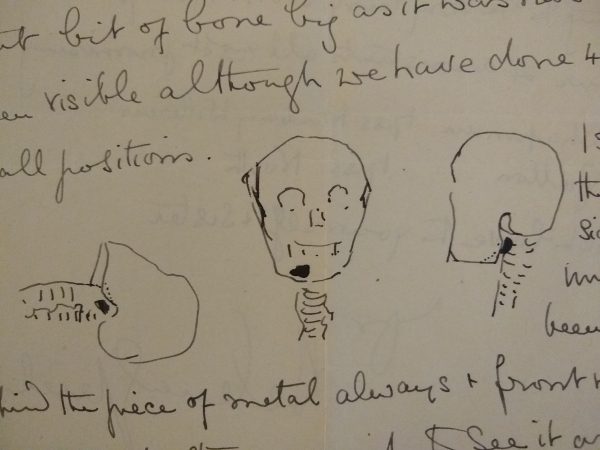

Lady Helena Gleichen provides one example of the uptake of these methods during the war. Gleichen practised radiography on the Italian Front, having had her services refused by the British War Office, something bemoaned by another correspondent of Mackenzie Davidson, the physicist Edith Anne Stoney: ‘There are many thousands of women sisters & V.A.D.s working in places of considerable danger […] why not a woman radiologist?’ (MS/929/1/209) As detailed in one of her letters, Gleichen completed around 12,800 radiographic examinations throughout her two years in Italy, working in 57 different field hospitals and abdominal sections (MS/929/1/86). She wrote frequently to Mackenzie Davidson of her experiences, and her letters often describe the interesting or complex cases she encountered, including this case of a soldier with a piece of shrapnel in his neck (MS/929/1/81):

MS/929/1/81

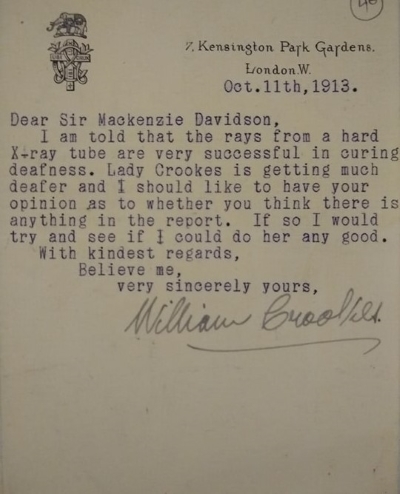

Two future Presidents of the Royal Society also show an interest in Mackenzie Davidson’s radiography. Sir William Crookes, for example, writes to Mackenzie Davidson on the subject of his wife’s deafness and asks if X-rays would help stall its progression (MS/929/1/41), while Sir Joseph John Thomson’s exchange with Mackenzie Davidson is (perhaps unsurprisingly) on the subject of cathode rays (MS/929/1/215).

Letter from Sir William Crookes, 1913, MS/929/1/41

Other prominent correspondents hint at Mackenzie Davidson’s involvement in the ‘radium craze’ of the turn of the century. The discovery of radium by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1898 from the chemical analysis of pitchblende was followed by a huge surge in experimentation, with scientists everywhere trying to get their hands on supplies. Demand was so high that the Society created a Radium Research Fund in 1904, overseen by its newly established Radium Investigation Advisory Committee, exclusively to fund radium purchases and research.

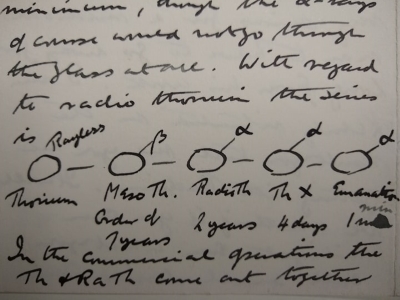

Some of the central figures in the ‘craze’, including Ernest Rutherford, Frederick Soddy and William Ramsay, write to Mackenzie Davidson on the subject. In one letter Soddy sympathises with Mackenzie Davidson on his recent loss of a packet of radium in the post (MS/929/1/187), while Rutherford regretfully informs Mackenzie Davidson that he has no spare radium to offer him this week (MS/929/1/165), and Ramsay excitedly relays rumours that pitchblende has been discovered in ‘the Cornish Mines’ (MS/929/1/157). Rutherford and Soddy’s letters often relate to questions of emanation, particularly that of radiothorium, perhaps indicative of their shared interest in emanation as radioactive decay. They also write to Mackenzie Davidson for his opinion on the uses of radiation, particularly radiation as a cancer treatment (MS/929/1/166) and – terrifyingly! – radium as a treatment for X-ray burns (MS/929/1/190).

Frederick Soddy’s illustration of the radioactive products of radiothorium, 1909

Though fascinating in these scientific insights, also radiating from the pages of this collection (too much?) is the personality of the man at the heart of it. There are few letters where Mackenzie Davidson is not thanked for his generosity and kindness by either a patient or a colleague, while the obituary material present refers to his commitment to radiography throughout his lifetime – a commitment that leaves his collection very much at home here within the archives of the Royal Society.