Royal Society Lisa Jardine Grant recipient Ivana BiÄak shares some anecdotes from her research trip to the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen.

I’m one of the inaugural recipients of a Royal Society Lisa Jardine Grant, and I’d like to share some historical animal anecdotes from my grant funded research trip to Copenhagen. My research at the Royal Danish Library complements my project at Durham University on the literary reception of early modern physiological experiments on human and animal subjects at the Royal Society and English universities.

‘As monkeys peeled off the wallpapers in one of the rooms, parrots rushed for the gilded mirrors.’

This is a description of a typical day in seventeenth-century Copenhagen Castle. Outside, lions, tigers and leopards traversed the grounds, and in the harbour one could see a polar bear. As in the rest of northern Europe, the exotic animals brought colour and amusement to the country’s royalty, noblemen and citizens.

Jean-Baptiste Oudry ‘Music-making Animals (“Air”)’, 1719 © Nationalmuseum Stockholm

Little did the mischievous animals know that not all publicity is good publicity. They aroused curiosity in the minds of the scientists of the period, who worked in the Anatomy House (Domus Anatomica), in whose ground floor Copenhagen’s first anatomical theatre was constructed. This institution, established in 1644, was at the forefront of European anatomical research, and it depended for its success on a constant supply of animal specimens.

Copenhagen’s Anatomy House. Illustration from Thomas Bartholin Cista medica Hafniensis (1662). Wikimedia Commons.

Danish archival materials should be paramount in the discussion of early modern science, medicine and literature in Europe. Danish anatomists were at the top of physiological research in seventeenth-century Europe, and they unfortunately remain overshadowed by Padua and Leiden. I set out to conduct research following in the footsteps of Niels W. Bruun, a renowned classical philologist and expert on Thomas Bartholin and the Anatomy House. In future, I plan to focus on Simon Paulli and his neglected work and writings.

Simon Paulli (1603-1680), the founder of the Anatomy House, engaged in a number of animal dissections. He perfected the process of drying and bleaching the animals’ bones and assembling their skeletons. Paulli is the author of a quaint little guide entitled On the Boiling of Bones. Thus, while the animal kingdom was busy redecorating the rooms of the palace, their less fortunate members were busy decorating the walls of the Anatomy House.

Theatrum Anatomicum. From the digital collections of Det Kongelige Bibliotek (Müllers Pinakotek Collection). Creative Commons.

Paulli had a loyal assistant, Michael Kirstein (1620-1678), a German physician who was said to be inseparable from his anatomical knife. Not only did Kirstein help Paulli dissect the animals and ‘dress’ them as exhibition pieces, but he also wrote Latin epigrams under their skeletons. He would record their medical history, contemplate philosophical questions, and sometimes let the animals speak in the first person. Alongside these skeleton accompaniments, Kirstein also wrote a Latin poem on a dissected monkey. His neglected verses offer an invaluable early portrayal of an experimental animal:

‘On a Monkey Irreverently Murdered’

A dreadful plot, a savage crime!

Three conspire against the life of an innocent monkey,

In an awful and heinous fraud,

And to their crime of conspiracy appoint the fourth one,

Pious in nature, and undefiled by offence.

They first proceed with poison: but when the cautious

Monkey spurns it, they arm their fierce hands,

And, preparing to use force, restrain her throat with rope.

It is done; she is held down, grows pale, expires!

But you, Borussus, and you, raging Berlinas,

And you, Moravus, monkey-murderers,

You will be pursued by the shadow, you will be pursued by the image,

You will be pursued by her menacing dying face, except if you

Rightly purge your impure hands, and, putting her to rest

In an illustrious place, not throwing her into putrid earth,

You revere her bones, saying from now on:

MAY THE AIR, NOT THE EARTH, REST LIGHTLY ON THE MONKEY.

The language of Seneca pervades the subject with tragedy and dignity. It is interesting that Kirstein involves himself in the murder accusation (he was known as Moravus). In another of his epigrams, he calls attention to the anatomical and behavioural similarities between humans and monkeys:

That the monkey imitates our own behaviour in other respects

Here you may see, as its bones agree with our bones. (‘Of a Monkey’).

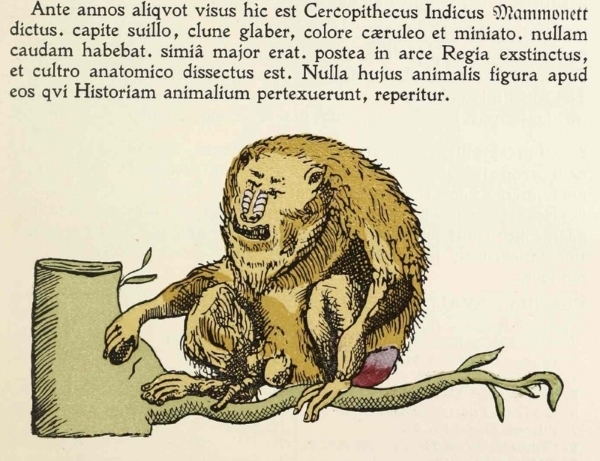

Several decades later, another monkey ended up on the anatomy theatre’s dissection table. Mammonett, a male mandrill, lived in the king’s gardens. Unlike Kirstein’s monkey, Mammonett died of a disease before he was cut up. Holger Jacobaeus, in his Rejsebog (1671-92), includes an illustration of the animal together with a short description:

Mammonett of Copenhagen. Illustration from Holger Jacobaeus Rejsebog (1671-92), p. 57.

Thomas Bartholin (1616-1680), Paulli’s celebrated successor at the Anatomy House, and the discoverer of the lymphatic system, reported on the dissection of Mammonett in his Acta Medica et Philosophica Hafniensia, the first Danish scientific journal. Describing the monkey’s large testicles, Bartholin recalled how the monkey used to sexually harass women in the castle.

Parrots were no less interesting to the century’s anatomists. Like monkeys, they appeared to imitate humans, if only in speech. Both species seemed to be intermediaries between the human and animal realms, and as such constituted interesting experimental subjects.

Jakab Bogdány ‘Still life with Fruits, Parrots and a White Cockatoo’, 1710s (detail). © Hungarian National Gallery:

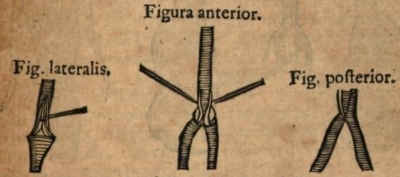

In the attempt to account for a parrot’s vocal abilities, Jacobaeus dissected a Psittacus (African parrot), and included illustrations in his report. The parrot was reduced to its constituent parts as if it were a little machine, an ingenious piece of clockwork that was capable of reproducing human speech.

Illustration from Acta medica et philosophica Hafniensia, 1673, p. 317.

Being an exotic pet in seventeenth-century Copenhagen thus seems to have been a double-edged sword. The castle’s gilded rooms and green surroundings could easily be replaced by a revolving dissection table. Curiously, after dissection, the animals lived on not only as skeletons but also in verse. These neglected poems written by scientists themselves tease out important bioethical questions concerning animal experimentation that we still have trouble answering today.

English-Danish scientific relations in the period are also part of my research – these were particularly fruitful, but remain seriously under-studied. In general, my Lisa Jardine Grant has enabled me to create a network of contacts at the University of Copenhagen, ranging from early career scholars to more senior researchers. The impact of the grant on my career has been tremendous. I have been able to locate rare books and uncover Paulli’s neglected speeches as well as Kirstein’s lesser known poems.

As a result of my research trip, I have been invited to present a paper at a conference in Copenhagen in spring. I also reached out to the Medical Museion in Copenhagen. Most importantly, I will spend four months at the Centre for Environmental Humanities in Aarhus this summer. Thanks to the Royal Society, I have been able to strengthen my research profile and engage in innovative interdisciplinary research in wonderful, wonderful Copenhagen.