Louisiane Ferlier looks at the 1681 catalogue of the Royal Society's Arundel Library, and how Fellows and librarians annotated their copies.

In a previous blogpost, I described my semi-successful hunt through the records of the Royal Society for a chameleon owned by Robert Boyle. I’m now picking up the thread to tell you more about some of our seventeenth and eighteenth-century library catalogues.

Various original sources can be used when trying to establish the destiny of a specific donation to the Royal Society. In the Journal Books and Letter Books, clerks often noted the gifts and specimens sent by correspondents across the world. Domestic Manuscript DM/5 (81–115) contains various lists from the earliest days of the Society. Donations were also sometimes publicised in the Philosophical Transactions in articles or later as lists of presents. These documents allow us to understand what people – mostly outside the Society – deemed worthy of interest, and what topics, texts, rarities and samples they hoped would be studied by the Fellows at their meetings.

If you want to know what the Fellows did with the [un]solicited items, and in particular whether they kept or disposed of something, the best sources of information are the catalogues and inventories put together by successive Keepers of the collections. For natural history specimens, such as the chameleon, Nehemiah Grew’s printed Musaeum Regalis Societatis and the manuscripts MS/413, MS/415, MS/416 and MS/417/1 are most useful; meanwhile, books are listed in MS/420 and other resources. As with the inventories of objects, some catalogues mingle printed sources and manuscript documents, but while the object inventories have been entered in the archival collections, the library catalogues are kept as printed documents with the book collection.

Whereas much attention has been paid to the archive and museum, the composition and use of the library by its Fellows remains a less-studied area of the Royal Society. Yet it seems Fellows did pay particular attention to their collection of books: nearly 10 years before the museum catalogue was published, the Society had already established rules for the use of its library and received the impressive Arundel Library as a donation from Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk and 22nd Earl of Arundel.

Prior to the donation, Council had repeatedly pestered Robert Hooke to inventory the existing collection and to start preparing a catalogue of the Arundel Library. On 13 September 1677 the Council charged a bookseller named Forster to team up with Hooke ‘for making a catalogue of the Arundel Library’. Looking through the Dictionary of the printers and booksellers who were at work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1668 to 1725, I could find no Forster active in London and from the handful of named Fosters, none seem to match our Forster.

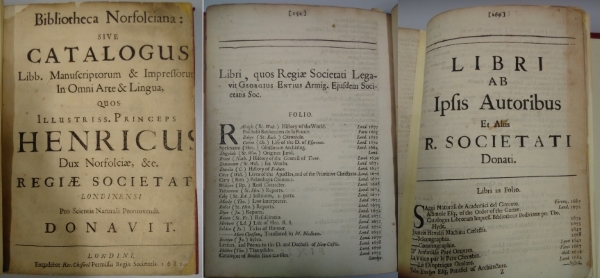

In any case, the 1681 publication of Bibliotheca Norfolciana sive catalogus libb. manuscriptorum & impressorum in omni arte & lingua resulted from the labours of many hands. The catalogue appears mainly as the work of William Perry FRS (c.1650-1696), first librarian of the Society (1679) and Professor of Music at Gresham College. In journal books for the period, we find mentions of Sir John Collins (1625-1683), Sir John Hoskins (1634-1705) and Peter Ball (c.1638-1675), as well as Robert Hooke, all working to improve the first catalogue, which also included the donation of George Ent’s library and a list of books given by their authors to the Society:

Bibliotheca Norfolciana, 1681 (RCN R81220)

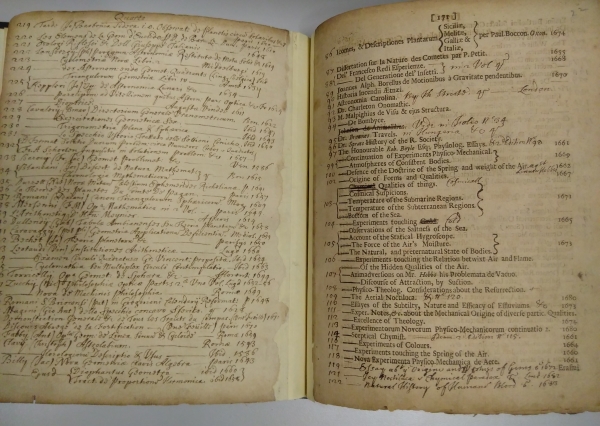

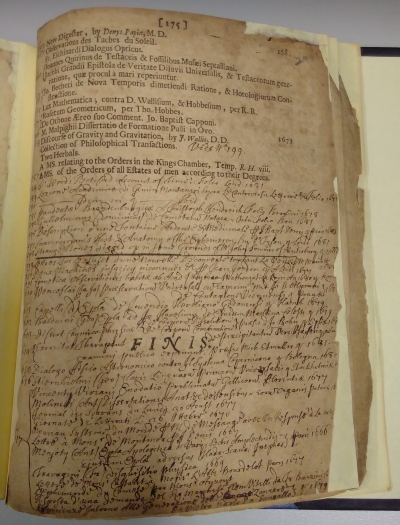

After its publication, the catalogue remained a living document as Fellows and librarians annotated their copies, adding or crossing out entries:

Bibliotheca Norfolciana, 1681 (RCN 18829)

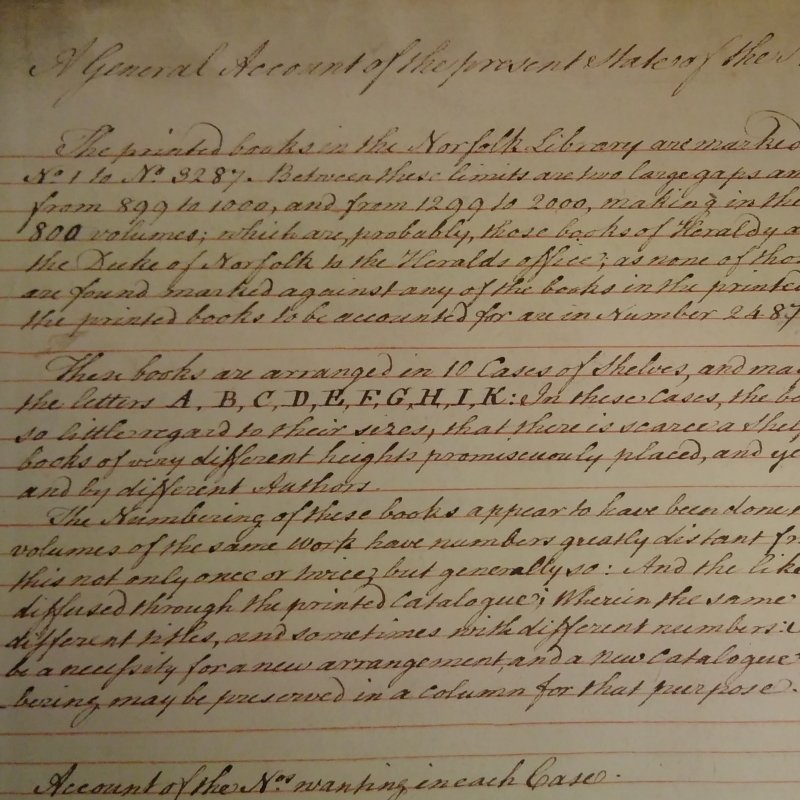

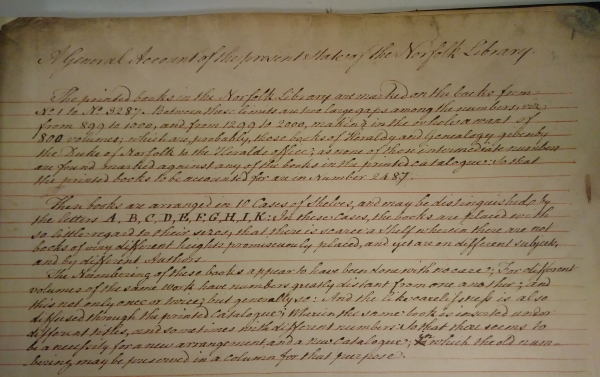

These annotations in our copy of the Norfolk catalogue have not been formally attributed, but Cambridge University Library holds a copy with Perry's own additions and the British Library has one with Hooke’s annotations. The catalogues were composed, printed and trimmed to accommodate the manuscript interventions of librarians, a common practice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The extensive notes in the margins of these published catalogues of books allow us to follow inclusions, dispersals and rearrangements within the collection. Long before the deaccessioning of most non-scientific volumes from the Arundel Library in 1872 and 1925, in MS/420 Librarian John Robertson noted that the donation of the books of heraldry from the Norfolk collection to the Herald Office created a gap of over 800 volumes in the numbering sequence.

MS/420, ‘An old catalogue of the Norfolk Library’

Along with the repository inventories, I must admit to being very partial to these catalogues: simply by meandering through their pages you can reconstruct reading practices and changes in the categorisation of knowledge. You can recreate the shelves of a library now disappeared or, with the help of the lending books, you can track which Fellows never returned their books. They are a precious help in digging up strata in the history of our collections, and powerful reminders of the great minds who browsed our shelves and of the diligent hands who had to tidy up after them.

Bibliotheca Norfolciana, 1681 (RCN 18829)