Following in the footsteps of traveller and antiquarian Thomas Pennant FRS, Rupert Baker reports back from Snowdonia and the 'damned water' of Llyn Idwal.

I didn’t drag the family quite as far as the Azores for our summer holiday this year, opting instead for a week in Snowdonia. Although the weather was typically mixed, we were lucky enough to have sunshine and blue skies on the afternoon we took the Snowdon Mountain Railway up to the summit.

The Snowdon Mountain Railway; Y Lliwedd from the summit of Snowdon; summit cairn from the Llanberis path down. Author’s photos.

At the time, I guessed that I was following a path previously beaten by many of our Fellows – the exploring instinct has been strong at the Royal Society since our foundation in 1660 – so when I got back to work I typed ‘Snowdon’ into our online catalogues to see which names came up. Sure enough, there were a few on the archival side: Edmond Halley carried out barometrical experiments at the summit in 1697, and some letters written in 1773 from Thomas Curtis to Charles Blagden allude to an expedition featuring Blagden and Joseph Banks. Blagden’s account to Curtis does not appear to have survived, so I can only lament Mr Curtis’s poor eye to posterity, even as I nod to him for being able to decipher Blagden’s famously terrible handwriting in the first place.

As my job focuses mainly on books rather than archives, the item that sent me scurrying downstairs to the collections was a print publication from 1781, The journey to Snowdon. Its author, Thomas Pennant FRS, was a Welsh gentleman with interests in natural history, antiquarianism and travel, who has been the subject of recent scholarly attention as one of the first writers to pen accounts of the wilder, more remote parts of Britain. Our copy was donated to us in 2011 by Sir John Rowlinson FRS, Physical Secretary and chair of the Library Committee when I started working at the Royal Society, and a keen mountaineer himself.

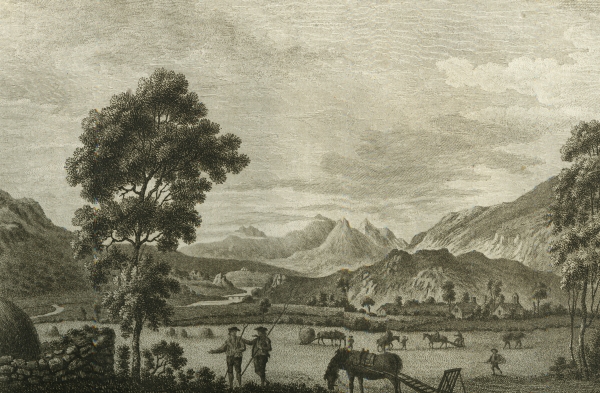

Pennant was as impressed as we were by the view from the summit of Snowdon: ‘I saw from it the county of Chester, the high hills of Yorkshire, part of the north of England, Scotland, and Ireland: a plain view of the Isle of Man; and that of Anglesea lay extended like a map between us, with every rill visible.’ Perhaps wisely, his artist and faithful travelling companion Moses Griffith didn’t attempt to delineate the whole 360° panorama on one of the plates in The journey to Snowdon, but his views of distant peaks still manage to capture the rugged beauty of the region. This one is Griffith’s ‘View in Nantberis’, showing Dolbadarn Castle near the present-day tourist centre of Llanberis:

and here’s ‘The summit of Snowdon from Capel Cerig’ (Capel Curig):

Pennant described this viewpoint as follows: ‘The small church of Capel Kerig, and a few scattered houses, give a little life to this dreary tract. Snowdon and all his sons … here burst at once full in view, and make this far the finest approach to our boasted Alps.’ From Capel Curig, Pennant sent the horses on to Llanberis, before ascending with Griffith into the Glyderau range to the east of Snowdon and visiting Llyn Idwal, about which ‘The shepherds fable, that it is the haunt of Daemons; and that no bird dare fly over its damned water, fatal as that of Avernus’.

Ascending above the demon-haunted lake, Pennant advises walkers to ‘Observe, on the right, a stupendous roche fendue, or split rock, called Twll-Du, and The Devil’s Kitchen. It is a horrible gap, in the center of a great black precipice.’ He adds that, ‘On surmounting all my difficulties, and taking a little breath, I ventured to look down this dreadful aperture, and found its horrors far from being lessened, in my exalted situation; for to it were added the waters of Llyn y Cwn, impetuously rushing through its bottom’.

Well, we did the same hike up through the Devil’s Kitchen to Llyn y Cwn (there being no handy train available) and, while not at all horrible or dreadful, it was certainly hard work. All worth it, though, for the spectacular view back over Llyn Idwal (below). Come to think of it, there are no birds visible in my photo, and I don’t recall seeing any that day – maybe those superstitious shepherds in Pennant’s account were right after all?