Read more about work of Italian astronomer and mathematician Annibale de Gasparis.

The year 2019 marks the bicentenary of the birth of Annibale de Gasparis, Italian astronomer and mathematician, Director of the Astronomical Observatory of Naples and Senator of the Kingdom of Italy.

Portrait of Annibale de Gasparis (1819-1892). Courtesy of INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Napoli.

De Gasparis discovered nine asteroids from the city of Naples, winning national and international awards including the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1851. Above all, he managed to connect Naples with the night sky, naming his second asteroid Parthenope, after the ancient Greek settlement originally founded on the site of the modern city.

The almost total lack of received correspondence from de Gasparis causes noteworthy gaps in the detailed reconstruction of the events of those years, in which ‘the sky of Naples, by means of his endeavours, could almost be called the favorite garden of asteroids’, as the Modenese astronomer Giuseppe Bianchi wrote in 1851. Therefore the study of the correspondence of John Herschel, the majority of which is held in the Royal Society Archives, helps to fill in the gaps regarding the discovery and dedication of de Gasparis’s new ‘planets’ (as asteroids were still thought of at the time), and in particular Parthenope, a name with such local associations for de Gasparis himself.

This name was proposed by Herschel for Gasparis’s first asteroidal discovery on 12 April 1849, though Ernesto Capocci, (then) Director of the Specola of Naples, had already chosen the name of the goddess of health and cleanliness, Hygiea.

Looking through Herschel’s correspondence, I found at least two letters in which the English astronomer discussed the most suitable name for de Gasparis’s first asteroid. At that time, Herschel was working on the publication of the second edition of his treatise Outlines of Astronomy, and asked Professor Augustus De Morgan for suggestions to revise it. This time, Herschel also questioned his valued friend about the discovery of the new planet:

‘No name has yet been mentioned. What do you think of Parthenope (being a Neapolitan?) I should think it will occur as a matter of course to Gasparis if he has any classical reading.’ (April 1849, letter HS/23/66)

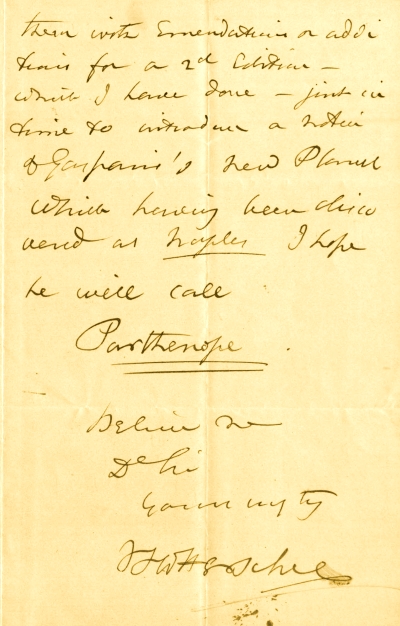

In the same context, he wrote also to James David Forbes, Scottish physicist and glaciologist, mentioning ‘Gasparis’s new Planet which having been discovered at Naples I hope he will call Parthenope‘ (1 June 1849, ref. St. Andrews 48):

John Herschel to J. D. Forbes, 1 June 1849. Courtesy of the University of St Andrews Library, msdep7 – Incoming letters 1849, no.48.

It seems that Herschel’s intention was to test the ground to see if his suggestion would be accepted. It went somewhat against the usual custom: in mythology, Parthenope was simply a mermaid and not a goddess, unlike the names of all the other planets.

De Morgan and Forbes were not the only ones whom Herschel asked for advice. On 26 June 1849, Heinrich Christian Schumacher, then director of the Altona Observatory, complained in a letter to Herschel that the name of the new Neapolitan planet appeared to be written with the Italian spelling ‘Igea’, and not in the Latin form as used for all the other planets:

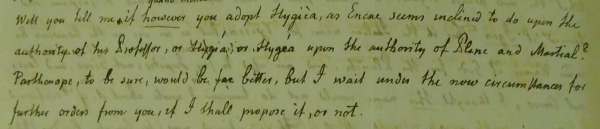

‘Well tell me if however you adopt Hygièa […] or Hygia or Hygea upon the authority of Pline [Pliny] and Martial? Parthenope, to be sure, would be far better, but I wait under the new circumstances for further orders from you, if I shall propose it, or not’ (26 June 1849, HS/15/403).

H. C. Schumacher to J. Herschel, 26 June 1849. HS/15/403 © The Royal Society.

Words which undoubtedly suggest that Herschel had discussed his idea with Schumacher as well.

We do not know when and how Herschel’s suggestion reached Naples, though it was probably through a letter addressed to Capocci. However, is it clear that Herschel considered the name ‘Parthenope’ instantly, but preferred to learn more about the opinion of other European scientists and astronomers before suggesting it to the discoverer. Eventually Herschel also informed de Gasparis of his suggestion, even though the name Igea had already been chosen in Naples more than a month earlier by Capocci.

The Reichenbach equatorial telescope in the northern dome of the Naples Observatory, 1929. With this small telescope de Gasparis discovered his nine asteroids. Courtesy of INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Napoli.

De Gasparis was obviously keen to please a great astronomer such as Herschel, however, so when he discovered a second asteroid on the night of 11 May 1850, he had no doubt about its name. Indeed, once he confirmed the discovery, he wrote a series of letters to Italian and European colleagues to inform them. First of all, naturally, to John Herschel:

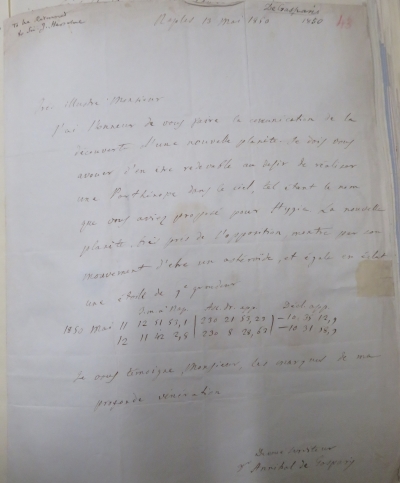

‘J’ai l’honneur de vous faire la communication de la découverte d’une nouvelle planète. Je dois vous avouer d’en être redevable au desir de réaliser une Parthenope dans le ciel, tel étant le nom que vous aviez proposé pour Hygie.’ (13 May 1850, HS/8/43)

Annibale de Gasparis to J. Herschel, 13 May 1850. HS/8/43 © The Royal Society.

With the discovery of his second asteroid, thanks to Herschel’s classical knowledge and prompting, Annibale de Gasparis succeeded in creating a Parthenope in the sky, commemorating the site of his observations.