Brush up on some cheese facts prior to the festive season, courtesy of the Royal Society's records.

The festive season is officially upon us and the gastronomical over-indulgence of Christmas has already begun for me. For some that may mean too many mince pies or mulled wine, for me it’s cheese. I therefore decided to seek out records of cheesemaking in the Royal Society archive as our festive blog offering.

As the early Fellows of the Royal Society subscribed to the ideals of Francis Bacon, including collecting and recording information on the skills and knowledge of different trades, I felt sure there would be some dairy-based gems going back to the seventeenth century, and I was not disappointed. As Dr Paolo Savoia points out in his article ‘Cheesemaking in the Scientific Revolution‘, natural philosophers of the time were also keenly interested in the topic as an example of the transformation of one substance into another – and if you ask me cheesemaking is the best kind of chemistry, a kind of delicious alchemy.

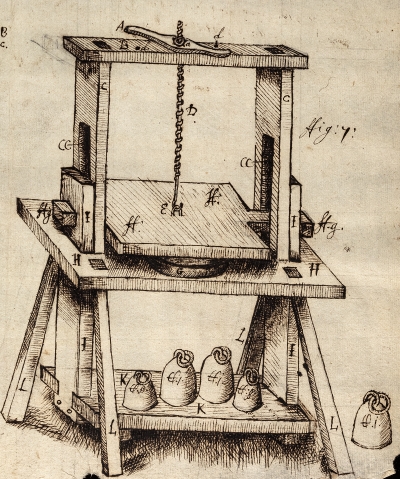

One of the oldest documents I found in the archive was a letter from a William Jackson, who wrote a very full description of the cheesemaking process. From the production of the rennet needed to set the cheese (done by hanging curds to steep over a fire in the stomach of a calf for at least half a year, which I will definitely not be thinking about when eating my Christmas Stilton), through to the pressing of the cheese in a specially designed mechanical press, to methods of making sure rats are kept away from the cheese while it is seasoning, he is meticulous in his description.

A cheese press, from William Jackson’s letter. ‘A thorough Dayry woman should have 2 of these presses else she will be at a loss some times’ (Cl.P/3i/22).

Two guesses where he wrote from. If your first guess was Cheddar, then hopefully your second was (correctly) Cheshire. Cheshire cheese is one of the oldest named cheeses from Britain, with written records going back to the sixteenth century, and the county of Cheshire is known to have been a centre of dairy production since at least the twelfth century (these and other useful (?) cheese facts courtesy of the excellent new book A Cheesemonger’s History of the British Isles by Ned Palmer).

The kind of specialised (and sometimes regionally-specific) knowledge developed by centuries of expert artisans would have been passed down orally and through practice to family members and apprentices. Thanks, however, to the information-gathering and recording of the early Fellows of the Royal Society, we have this valuable document detailing traditional British cheesemaking, including illustrations of the equipment and methods used.

Stretching the cheese, one method of transforming the curds into a soft cheese, from William Jackson’s letter (Cl.P/3i/22).

What we do not know from Jackson’s letter is exactly whose cheese production he was describing. Jackson was a medical doctor who seems to have collected this information rather than being a cheesemaker himself; he also wrote to the Royal Society regarding salt-works in Cheshire, and is described in the published account as ‘learned and observing’. It seems that he gathered information from many different cheesemakers, and there is mention of some who will not use rennet until it has steeped in that calf stomach for a whole year, whilst others hang it for a shorter time, presumably determined by how long they could bear the smell! It seems clear however that whoever Jackson’s cheese sauces were, they were women.

At a talk given by the aforementioned Ned Palmer at my local literature festival, I was fascinated to discover that cheesemaking was traditionally the preserve of women, and this is borne out by Jackson’s account of Cheshire cheese production in which he talks about the practices of ‘huswifes’ and ‘dayrywomyn’. And in another seventeenth century manuscript in the archive, John Beale describes to Robert Boyle the deft skills needed to make cheese, only possessed by practised dairy maids.

Portrait of J. A. Voelcker, ca. 1862. Source: ArtUK – copy of painting in Royal Agricultural Society collection (public domain).

Moving on to the nineteenth century, I found an example of a male expert in cheesemaking: Augustus Voelcker was actually elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society by virtue of his cheese-pertise. The citation on his election certificate reads: ‘conductor of numerous field experiments in the chemistry of agriculture’ including ‘on the Chemistry of Milk and Cheese’, though he is apparently better known for his rather less appealing agricultural economics, involving the calculation of the annual value of a person’s excrement. Funny how they didn’t mention that on his certificate…

Cheese next makes a significant appearance in the activities of the Royal Society at the outbreak of the First World War. We recently blogged on the Society’s Food (War) Committee, and sure enough, on a list in the committee minutes of alternatives to traditional consumables, amongst dogfish, soya beans, horse chestnuts and industrial alcohol we also find suggestions for cheese substitutes. The Society was most interested in a method advocated by Warren Crowe, who claimed that his method of making soft cheese with bacteria rather than rennet, and incorporating coconut fat, produced a more nutritious product at greater yield per gallon of milk. He also reckoned that the process was quicker and did not require skilled cheesemakers, and the cheese could be preserved for longer.

Letter from T H Middleton, of the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries, to William B Hardy, 1 February 1917 (MS/527/2/9/2).

The Committee observed Crowe’s process (carried out by women), tasted his cheese and had samples analysed. They determined that though the product did seem economical, Crowe’s cheese was not of greater nutritional value and that there was ‘no public appetite for soft cheese’. Given the urgency of preserving milk, however, they urged him to direct his experiments towards making hard cheese in factories. In the end Crowe returned to military service and abandoned cheese production for the duration of the war. However he was part of a trend towards government-subsidised factory production of cheese, damaging to the traditional farmhouse methods described centuries earlier by William Jackson. Thankfully these days we have a multitude of artisan UK cheeses to choose from, and I will be filling my cheese board this Christmas with Wigmore, Yarg and Caerphilly.

Some of my colleagues were sceptical of the Christmassy credentials of cheese, but to give you an idea of how udderly seriously we take these matters in my family, I will come out and confess that we have a WhatsApp group called ‘Christmas cheese’ so we can make sure everyone’s favourite is on the cheese board. The suggestions start coming in round about October – the fact that there were only six cheeses sanctioned for production in the UK during the Second World War is anathema to the founding principles of this group, and the results are an epic cheese-spread and an annual shortage of crackers. With that I wish you all a Gouda Cheese-mas, and I’m off to eat my weight in Somerset Brie.