Read about how the Royal Society played a part in the evolution of cider, with numerous papers being submitted about its production and refinement.

In these days of trendy craft beers, artisan gin and molecular mixology, sometimes only a traditional beverage will do. One drink that fits the bill perfectly is cider – fruity, fizzy and refreshing, it’s a true staple of any pub in Britain. In fact, according to research, the UK is the largest per-capita consumer of the stuff! The Royal Society certainly played its part in the evolution of cider, with numerous papers being submitted about its production and refinement.

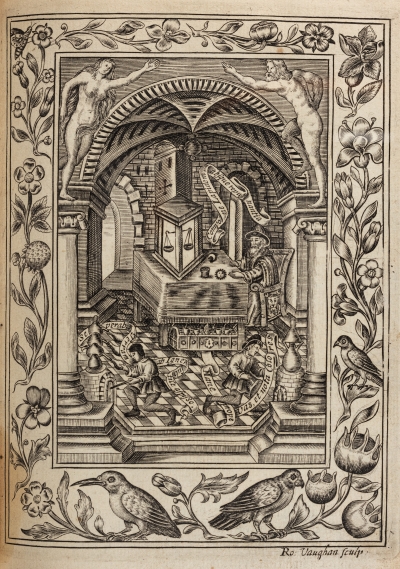

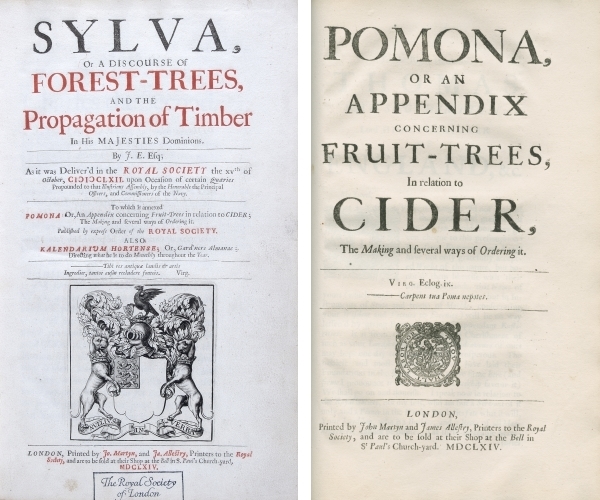

Cider has been produced in Britain since Norman times, when traditions of apple growing and cider making were brought over from France. There was something of a boom in consumption in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and numerous mentions in our early collections of the production of cider (or ‘cyder’ as it was spelt then). Perhaps the most notable is the first book published by the Society, Sylva; or, A discourse of forest-trees, and the propagation of timber (1664) by John Evelyn FRS, which is famed for its descriptions of British forestry and includes an appendix, Pomona, focusing on cider-making. A chapter in the appendix by John Beale FRS, entitled ‘General advertisements concerning cider’, compares the merits of different kinds of apples and gives suggestions on what routines should be followed in cider production. Beale was a prolific writer on the subject, with a number of his letters read at the Royal Society.

Title page of John Evelyn’s Sylva, with the separate title page from the Pomona appendix featuring John Beale’s chapter on cider

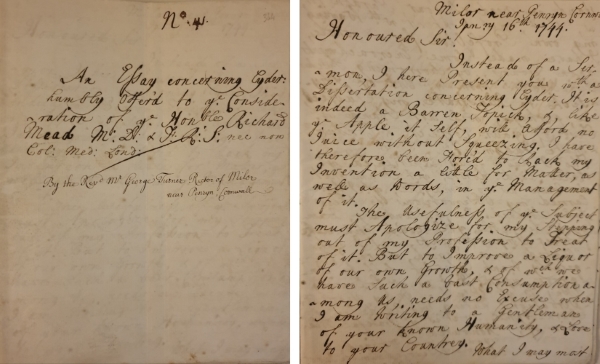

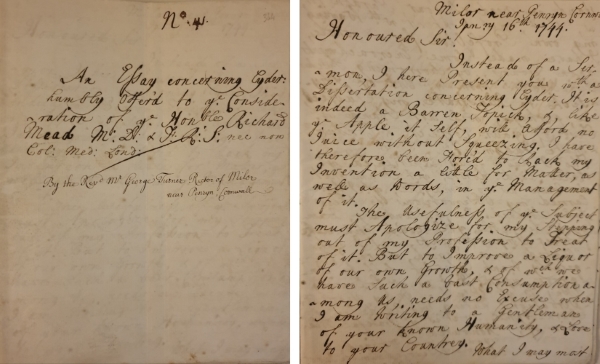

While trawling through the Society’s extensive Letters and Papers collection (1741-1806) as part of my new cataloguing project, I came across a paper about cider-making from a rather unlikely source: a Reverend George Turner from Penryn in Cornwall, who contacted the Society with his thoughts on the topic in January 1744.

The accompanying letter (L&P/1/364) offers a charming introduction to his paper. He states: ‘Instead of a sermon, I here present you with a dissertation concerning cyder. It is indeed a barren topick, and like the apple itself, will afford no juice without squeezing’. Turner conveys his ideas with humour, recognising that, as a man of the cloth, he is a somewhat surprising source of knowledge about alcohol production. He apologises for ‘stepping out of my profession’, but believes it is of the utmost importance to ‘improve a liquor of our own growth and of which we have such a vast consumption’.

Extract from the Reverend John Turner’s paper concerning cider (L&P/1/364)

So how does one go about producing one’s own cider? Turner recommends first letting your apples drop from their trees and benefit from the heat of the sun. They should then be picked up and left in a secure place without doors (a closed location would give the apples a ‘musty’ taste). A covering should be erected over the apple heap, supported by four sticks for easy access. The heap of apples should be left for almost a month, then pounded and squeezed before being transferred to a large vessel. Something should be placed in the vessel to collect the dregs after which it will require ‘several rackings’ to prevent it from ‘over-working’.

Turner seems to have a penchant for medical metaphors, claiming that if these rackings aren’t done, the cider could become ‘like a man with incorrigible diarrhea, or a violent super-purgation’ and be ‘incurable’; a racking acts as ‘a well-timed bleeding in a fever’. He advocates mixing the liquids to produce a taste according to its maker’s preference, and then transferring the result to a hogshead for storage. The person employed in the management of the cider should be ‘as cleanly in his cellar as a maid in her dairy’ and must take to care to wash straining bags, racking tubs and buckets. Then, the fresh cider should be transferred into bottles and plugged with a cork.

Turner believes in the (unconfirmed) medical merits of cider, claiming that it can act as a ‘cooler of the blood, when taken in a moderate way’ while admitting that a physician’s opinion should be considered above his. He also believes the Navy would benefit from having a cider store on their ships during long voyages.

Politics is also touched upon – Turner hopes his paper doesn’t fall into the hands of a Member of Parliament who is from one of the eastern counties of Britain. Hailing from Cornwall, Turner believes that people from the East ‘may not have a natural love and affection for the counties fame’d for cyder, and so, in envy to our singular happiness, move for an additional duty upon cyder.’ This was something of a premonition: 19 years later, a national tax was indeed levied, resulting in the ‘Cider Riots’ in the West of England. The tax lasted only three years before being repealed. Turner also believed that the British should be weaned away from their affection for French brandy and wine, as buying from the French is the equivalent of putting ‘a sword into our enemies hands to destroy us’, and as a result we will ‘become our own executioners, in the use of these pernicious liquors!’

While it is clear that the Reverend Turner is a true advocate of the benefits of cider, unfortunately his paper was not published by the Royal Society, for reasons unknown. As far as I can tell, he submitted no other papers, but I like to think that he was undeterred by his rejection, continued with his refinement and promotion of cider and lived apple-y ever after.