“We were surprised to see that their loneliness, depression and anxiety did not increase under self-isolation.”

Royal Society Open Science issued a call for Registered Report submissions in March 2020 to support research into the COVID-19 pandemic. This week the journal published the first of these contributions. The authors, Netta Weinstein and Thuy-vy Nguyen explain the motivation for and findings of their work below. Chris Chambers, the journal’s Registered Report editor concludes the blog with a summary of the call for papers to date.

In the run-up to lockdown psychologists feared the impact self-isolation could have on mental health. We worried that adults, and especially older ones, would feel lonely, depressed and anxious when stuck at home. These expectations were exacerbated by the unknowns: what is self-isolation going to be like, how will basic needs be met, how long will it last? Many of the relationships and commitments that brought us together and that occupied our days were, at best, now remote.

Since many people live alone; roughly 30 percent of adults in the UK, we feared that we would start to see the consequences of loneliness en masse. Researchers have reason to be worried about how those living solo would deal with self-isolation. The risks of loneliness are well known following decades of studies, including physical health problems so taxing they shorten our lives. Self-isolation seemed a necessary but costly decision.

It is hard to think about people stuck at home alone without imagining their loneliness. We expected self-isolating adults who live alone to feel especially cut off during these hard times while those of us who live with partners or family would be insulated by companionship.

But the findings of early studies run over the past couple of months do not support this assumption. We have been surprised by what they show. Our study published last week in Royal Society Open Science is one of them, which set out to identify differences in people that would affect their ill-being in self-isolation. We followed approximately 800 living-alone adults in the US and UK, and measured their loneliness, depression, and anxiety in the early weeks of the COVID-19 crisis. We had first measured their mental health before lockdown took full force, and again measured mental health at two time-points after. We were surprised to see that their loneliness, depression and anxiety did not increase under self-isolation.

There were more surprises in our results. We found that individual differences at the outset, those we thought would make people more resilient in isolation, didn’t matter. For example, people who preferred to be in the company of others did not seem to struggle more during these weeks of the crisis, nor did those who reported feeling more pressure to be alone. Both living-alone adults (around ages 35-55) and older adults (mostly 65-75) reported, on the whole, low ill-being in early weeks of the pandemic.

What we’ve learned from our earlier research on solitude may explain why: we don’t have to be lonely when alone, and solitude can be a positive space for reinvigorating, rather than depleting, our minds. As more people are at home than ever before, data collected by YouGov suggest that most people don’t want to go back to the way things were. Many of us are enjoying aspects of time alone, valuing simple activities such as a walk outdoors or cooking a meal. For many, these positives may be enough to balance the negatives of self-isolation.

These findings question whether initial concerns around mental health have been over-simplified and generalized. Conversations about mental health are often focused on the negative impact of self-isolation. But we found that other worries were more prominent. Some people who were worried about their health felt more lonely, depressed, and anxious, on the whole. Others worried about the stability of their jobs and incomes. Of course, isolation plays a role in these concerns if people don’t have a social support system in place to discuss those fears. Fortunately, we’ve seen both grassroots and top-down efforts across the UK and in the US to support adults and older adults with these concerns.

Psychologists are continuing to track people’s mental health through this crisis, and with good reason. As people linger in self-isolation they may become worn down by extended time alone. We do not yet know if and when this will happen, and what it means for mental health over the long term. For now, our data suggest more solitude has not been good or bad, it just was – and for many living alone adults and older adults, the extended time in self-isolation may be the lesser of the problems posed by COVID-19.

Netta Weinstein and Thuy-vy Nguyen’s research is concerned with contextual, motivation and well-being aspects of solitude, or time spent alone; https://www.soarinsolitude.info. This research is funded in part by the European Research Council (ERC).

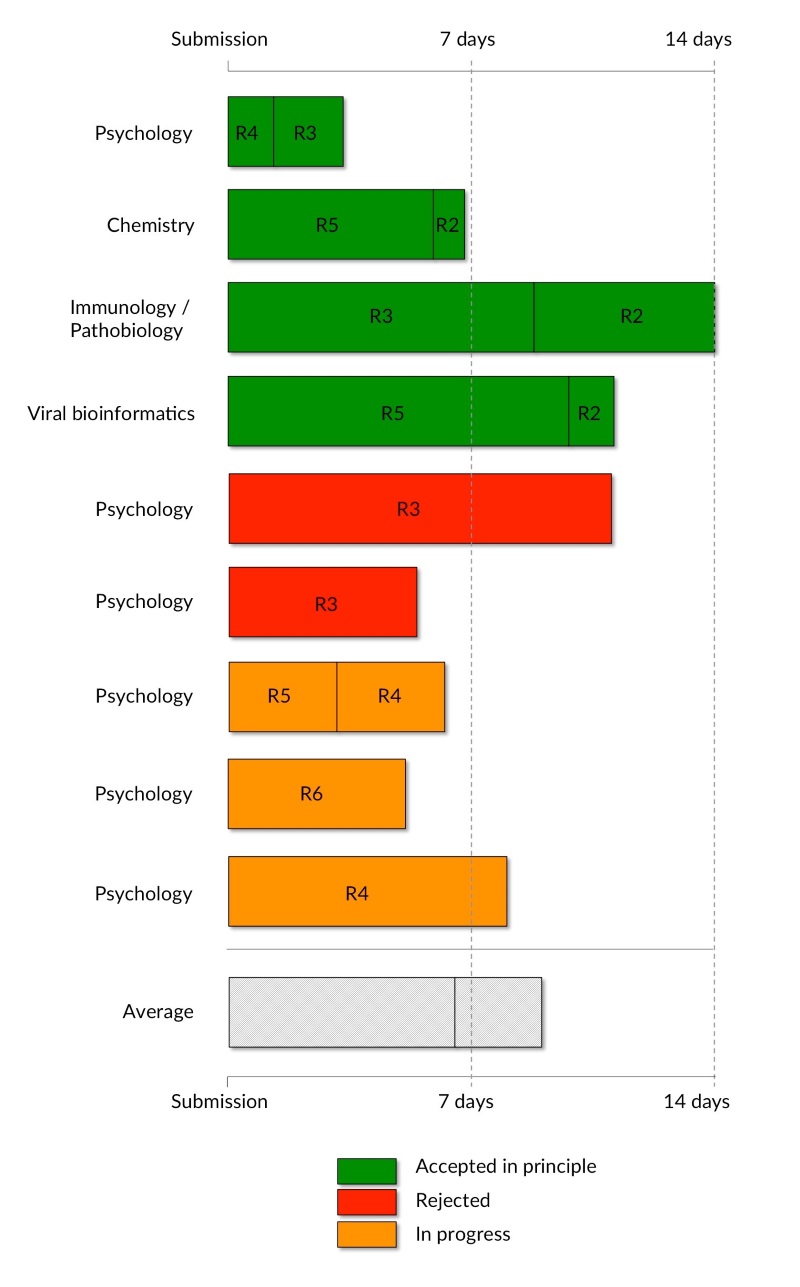

Prof Chris Chambers, Registered Reports Editor for Royal Society Open Science, adds that this publication is an example of a Registered Report reviewed at pace. Regular Registered Reports typically spend 2-3 months in Stage 1 review prior to in-principle acceptance, but thanks to the more than 800 scientists who have joined our COVID-19 rapid review network (in which reviewers commit to assessing Registered Reports within 48 hours), the total Stage 1 review time for COVID-19 Registered Reports at Royal Society Open Science is just over 1 week. This figure shows the number of days that each submission, so far, has spent in Stage 1 review, including two rounds of review where applicable. RN indicates the number of reviews received per round, including, for some submissions, a specialist editor in addition to the Registered Report subject editor. Note that these statistics capture the journal handling time only, and do not include the amount of time taken by authors to revise their submissions following review.

Since Royal Society Open Science is an open review journal, all reviews and editorial decision letters will be published alongside accepted Stage 2 articles. Registered Stage 1 protocols for the four submissions, so far, that have received in-principle acceptance are publicly available at the links below:

• Weinstein and Nguyen (psychology): https://osf.io/g9dxb/

• Jacobi et al. (chemistry): https://osf.io/y54h3

• de la Fuente et al. (immunology/pathobiology): https://osf.io/xhdpu

• Khan (viral bioinformatics): https://osf.io/ym8gc/

The journal invites Stage 1 Registered Report submissions from researchers, and to support COVID-19 research article processing charges for accepted Registered Reports will be waived.

Image source: Anders Eriksson, The lonely Reader, Copyright © Photomiqs - Anders Eriksson All rights reserved. Resized: 800x800