Ellen Embleton considers how the Royal Society Picture Library can highlight the contributions of enslaved and indigenous peoples to fields such as entomology and botany.

As our earlier Black History Month blogposts have noted, Western scientists working in Africa and the Americas during the colonial era consistently failed to acknowledge the contributions of indigenous and enslaved African peoples in the ‘discovery’ and understanding of certain specimens and practices.

With the Royal Society Picture Library full of entomological and botanical prints and drawings from this period, it’s up to Picture Library staff to attempt to highlight what contemporary scientists, and subsequent curators of their work, omitted: the various and numerous recoverable contributions of enslaved and indigenous peoples to this field.

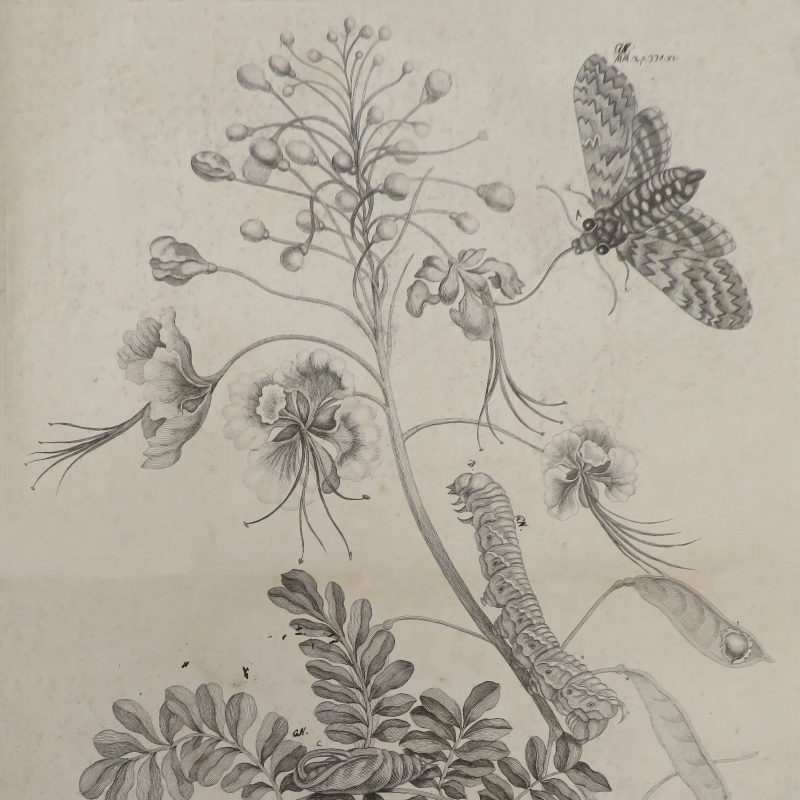

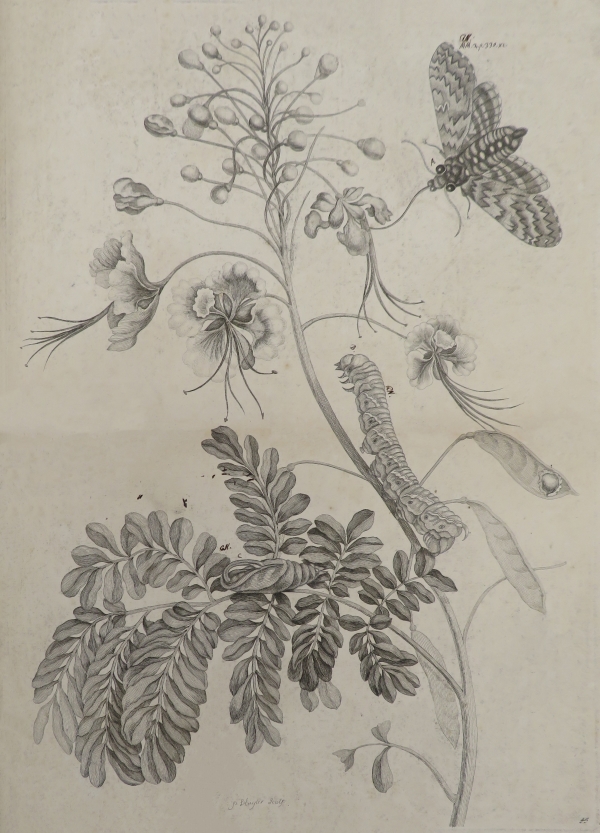

The question we are faced with is this: how do we make available on our database what is often obscured in primary source material? The simple answer: with some difficulty. Even in instances where the transfer of knowledge from enslaved people is mentioned, for example in the 1705 Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium by Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), we run into problems. The description to plate 45 (below) provides an insight into the toxicity of what Merian calls the peacock flower, Flos pavonis, the root of which was identified by enslaved African women in Suriname both as an abortifacient (a substance that induces abortion) and as a means of taking their own lives:

‘They often use the root of this plant to commit suicide in the hope of returning to their native land through reincarnation, so that they may live in freedom with their relatives and loved ones in Africa while their bodies die here in slavery, as they have told me themselves.’

Flos pavonis: plate 45 from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (1705)

This provides a sobering insight into acts of resistance by Black women in the face of a slave economy and sexual economy that abused their bodies. However, this knowledge of the abortifacient qualities of Flos pavonis was discredited by subsequent generations of botanists in the West, and Merian’s work criticised for its inclusion of such ‘idle stories’.

It is this racist culture of silencing, and the dearth of records documenting the lives and fates of the enslaved, that problematises our efforts at re-evaluation. In the face of this, one of our first steps when cataloguing images from the work of Merian and others like her should be to introduce our researchers to what little information from the enslaved filtered through into European accounts.

Ideally, the next step in this model of identification would be to determine the local or ethnic background of the people involved in such transfers of knowledge. While Merian does note that these women were displaced from Angola and Guinea, chiming with what we know of enslaved populations in Suriname, the lack of effort to explore Black contributions to science, and the subsequent sparsity of detail present in our collections, severely reduces our ability to confirm this or identify a more precise lineage.

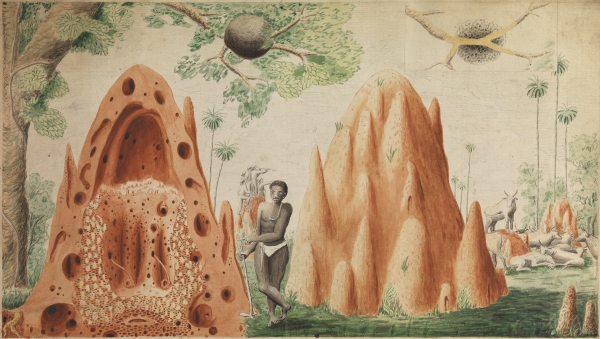

Our successes on this front are more common in instances of indigenous African contributions to the science of encroaching Europeans, though these still require a pulling together of fragmentary information. Consider the watercolour below, painted by Henry Smeathman (1742-1786) and depicting a termite colony in Sierra Leone:

An unnamed man depicted leaning on an axe, pointing to a termite colony (L&P/7/188)

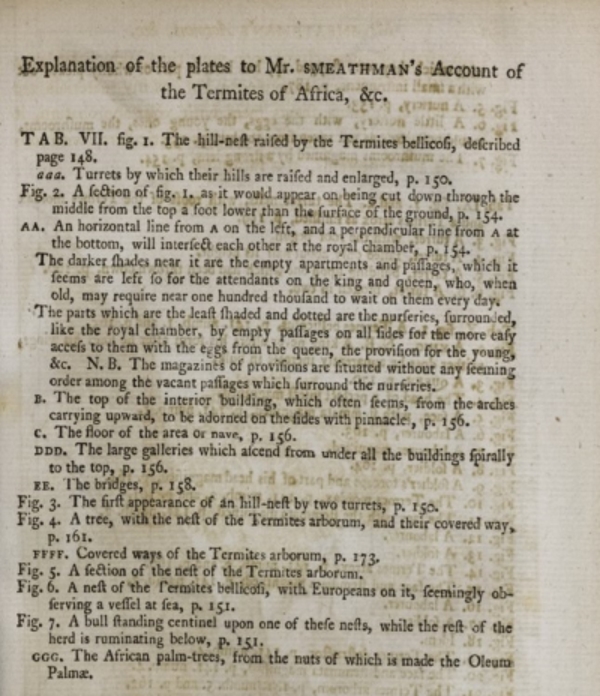

Smeathman’s explanation of this scene fails to mention the man in the foreground, who has clearly cut into the colony and possibly even guided Smeathman and his party to it:

‘Explanation of the plates to Mr. SMEATHMAN’S Account of the Termites of Africa &c.’, Philosophical Transactions vol. 71 (1781)

However, a close reading of the accompanying paper, ‘Some account of the termites, which are found in Africa and other hot climates’, provides little snippets of much-needed historical context. Early on in the paper, Smeathman explains that the termites in question are ‘known by various names’. Amidst a list citing the numerous French, Portuguese and English terms for them is a word from the Bolom [bolomdÉ›] language of the Sherbro people: ‘By the Bolms, or Sherbro people, in Africa, Scantz.’

The paper also refers on a number of occasions to ‘information which was given me by the natives’, and alludes to the presence of indigenous guides. Finally, buried in a footnote towards the end, is a description of the locals’ method of catching and eating termite soldiers:

‘… at the time of swarming, or rather of emigration, [termites] fall into the neighbouring waters, which [the indigenous people] skim off with calabashes, bring large kettles full of them to their habitations, and parch them in iron pots over a gentle fire … In that state, without sauce or any other addition, they serve them as delicious food; and they put them by hande-full into their mouths as we do comfits. I have eat them dressed this way several times, and think them both delicate, nourishing and wholesome…’

That Sierra Leonean practices such as this enriched Smeathman’s research is undeniable; in fact, historical examples of entomophagy continue to inform modern-day studies. Upon a close reading of this paper, it seems likely that knowledge came specifically from the Sherbro people, the native residents of the Bonthe district of Sierra Leone, who were among the first to interact and share land with European settlers. In the absence of a name for the man in our watercolour, we must instead harness these details to identify the possible ethnographic origin of this knowledge.

Of course, such an eking-out of provenance information from source material is not always possible, with many institutions in the heritage sector struggling with a lack of time and resources. This is why an approach that appeals for insight from other collections and the public is so helpful. A collaborative approach to description helps to fill the blanks in our capacity and knowledge. Here at the Royal Society Library, we are united in agreement that filling those blanks, and better acknowledging historical African intellectual production, is an essential part of fully understanding our works of natural history, and we are grateful for any help that allows us to do so.