We hear from a PhD student at New York University about her project ‘Smallpox and Slavery: Morbidity, Medical Intervention, and Enslaved People's Lives in the Greater Caribbean’.

Could you introduce yourself and your research?

I’m finishing my PhD at New York University. My current project, ‘Smallpox and Slavery: Morbidity, Medical Intervention, and Enslaved People's Lives in the Greater Caribbean’, addresses the histories of enslaved Africans who endured smallpox outbreaks, treatments, and public health interventions, between roughly 1520 and 1806, before the promulgation of the Jennerian vaccine. I’ve spent the last four years tracing West and West Central Africans’ macabre journeys across the Atlantic and through the Caribbean, where they cycled through compulsory health inspections, quarantines, treatments, and, in some cases, smallpox inoculations.

How did you discover the Royal Society archives and which records have you studied there?

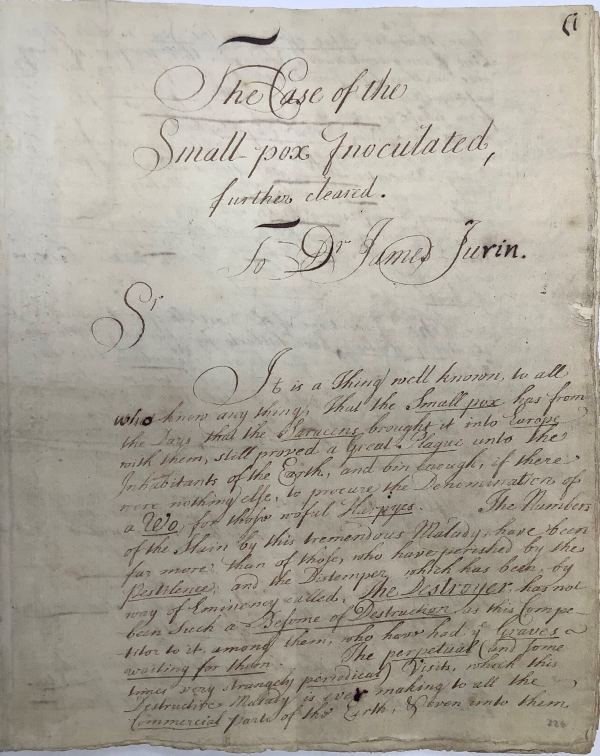

My interests in West African inoculators led me to the Royal Society’s Archives when I was a fellow at NYU’s London campus in 2018. My research there focused on James Jurin’s correspondence with physicians and scientists during his tenure as Secretary of the Society. The letters include reports and observations about smallpox inoculations performed on children and, to a lesser extent, adults, in England, France, and North America (primarily Boston and Charleston) during the 1720s and 1730s. The inoculations performed on enslaved and free people of African descent were most pertinent to my research.

Letter from Cotton Mather to James Jurin, 21 May 1723 (CLP/23ii/31)

As part of our exhibit ‘A Celebration of Black Science’ we mention the role played by the enslaved ‘Onesimus’ in introducing Cotton Mather to smallpox inoculation. Could you tell us more about the involvement of the Black and indigenous populations in the Caribbean and America?

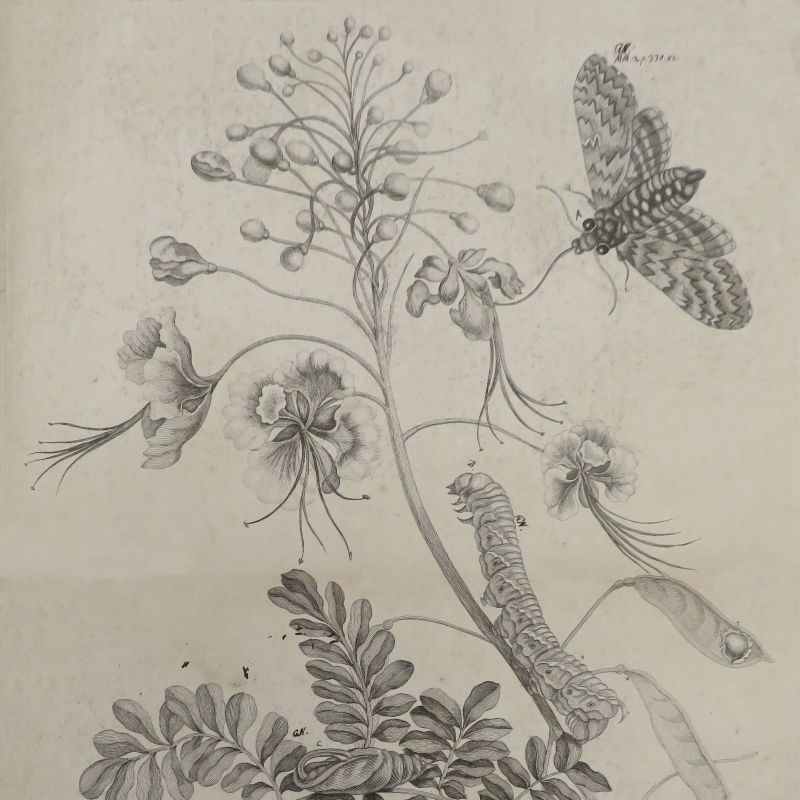

It’s important to note that smallpox inoculation relied on the presence of someone with smallpox pustules, which were pierced with a lancet to harvest pus that would then be inserted in an incision on another person’s arm or leg. This was a brutal process that ultimately resulted in a case of smallpox, though reputedly less severe. It controlled when, where, and how someone contracted smallpox, increasing their chances of survival. It did not prevent the illness or necessarily produce a mild case, but if someone survived they would typically have lifelong immunity.

In his Histoire de l’inoculation de la petite vérole (1773), French geographer Charles Marie de La Condamine stated that many West Africans had been practising smallpox inoculation since ‘temps immémorial’. The transatlantic slave trade violently dispersed West African communities throughout the Americas, where they continued and shared their medical practices including with their enslavers. The paucity of archival sources does not enable us to fully grasp the extent to which enslaved or free medical practitioners of African descent practised inoculation in the Americas before the early eighteenth century. However, a handful of surviving accounts suggest that they were practising it without European physicians’ oversight or knowledge by the turn of the eighteenth century.

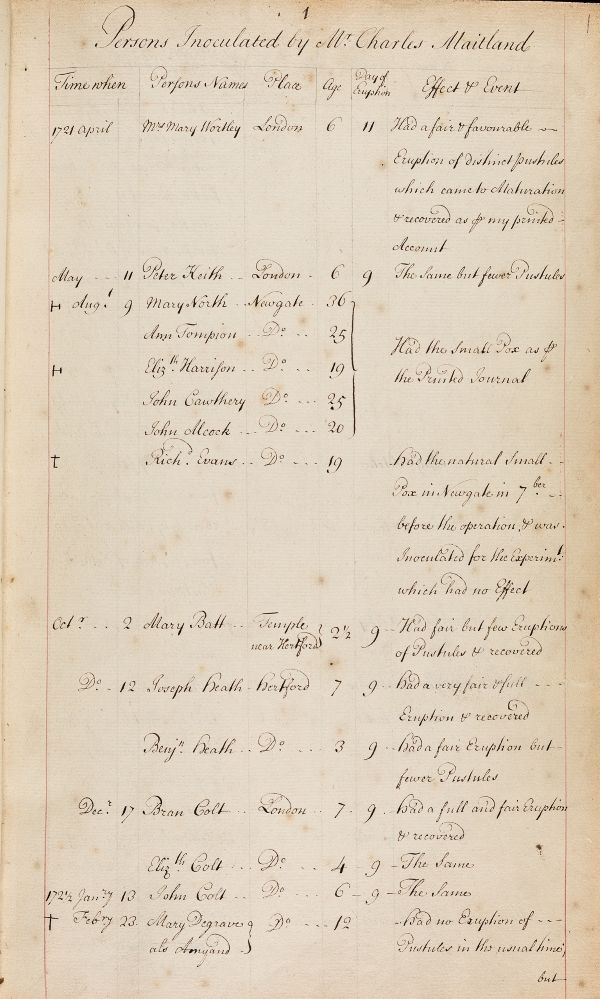

After the Royal Society published Emmanuel Timoni’s letter about smallpox inoculation in Constantinople, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s promotion of the idea, Europeans became more interested. After hearing about inoculation from Onesimus, Mather and several other ministers and physicians in Boston interviewed enslaved Africans, carried out their own tests, corresponded with the Royal Society and published accounts. In the 1720s, members of the Royal African Company sent a physician, James Houstoun, to oversee smallpox inoculations at some of their West African forts to control the smallpox outbreaks that frequently disrupted voyages.

In the Americas, pamphlets describing smallpox inoculation circulated widely in multiple languages, and reports began to circulate about Europeans inoculating enslaved Africans by the thousands in the Caribbean and North America. Nevertheless, the practice remained controversial and subject to occasional bans until the 1760s, causing some Europeans and Africans to perform smallpox inoculations without government or European physicians’ oversight.

By the 1750s and 1760s, metropolitan French and English learned societies endorsed smallpox inoculation, and authorities in the Americas began to restrict inoculation to licensed European or local physicians. Enslaved Africans who continued to practise smallpox inoculation among themselves found themselves subject to increased colonial oversight and the arrival of European inoculators.

The widespread acceptance also ushered in an era of experimentation. Men like John Quier exploited smallpox epidemics as opportunities to perform brutal (even by contemporary standards) experiments with purgatives and inoculations on infant, elderly and pregnant enslaved people. Late eighteenth-century Caribbean and European newspapers were peppered with propaganda advertising European-trained inoculators who would inoculate enslaved Africans to hone their skills or establish their practices before expanding to free white and non-white clienteles.

Many scholars have credited these inoculations as humanitarian efforts and therapeutic experiments. However, we should not ignore the uneven power dynamics and inherent violence associated with forcibly inoculating enslaved and colonised people to ensure labour production and sustain imperial projects.

Versions of variolation were practised in Northern Africa, which seems to be Onesimus’s likely birthplace. Have you found evidence that variolation was practised in the Americas by enslaved people from other areas of the African continent?

Mather’s descriptions of Onesimus’s origins are somewhat inscrutable. The uncertainty arises from two of Mather’s letters to the Royal Society. In one, Mather uses the term ‘Guaramantese’ to refer to Onesimus and the other enslaved Africans who informed him about smallpox inoculation. In the other, he describes these Africans as having been inoculated ‘while they were yet in Barbary.’ Some historians of Western medicine conclude that Onesimus hailed from North Africa, specifically today’s Southern Libya.

By contrast, historians who specialize in the histories of Africa, the slave trade, non-Western medicine, and early modern Anglo-Atlantic literature, argue that Onesimus’s origins were likely sub-Saharan, either from the Gold Coast or the West African interior. Social and cultural historians agree that the majority of the enslaved Africans in Boston at this time hailed from sub-Saharan West Africa. There is little evidence suggesting that North Africans were enslaved there.

Several historians speculate that ‘Guaramantese’ was an alternative orthography for ‘Coromantee’, used in the Americas to describe Africans who departed from the Gold Coast region. Likewise, ‘Barbary’ may have been a quaint term for Africa as a whole. Onesimus’s description of inoculation aligns more closely with West African techniques than North African ones. The surviving archival sources do not offer historians any easy or definitive answers regarding Onesimus’s origins; nevertheless, for the last 45 years, numerous scholars have agreed that he was likely West African.

French and English accounts of sub-Saharan Africans from the West African hinterlands describe inoculation methods for smallpox and yaws (another pox-producing disease) which predate Western Europeans’ familiarity with the practice. Cadwallader Colden, a physician and natural scientist who immigrated to New York in the early eighteenth century, spoke with the West Africans he enslaved and surmised (in his Medical Observations and Inquiries) that smallpox inoculation ‘came from Africa originally with the distemper itself.’

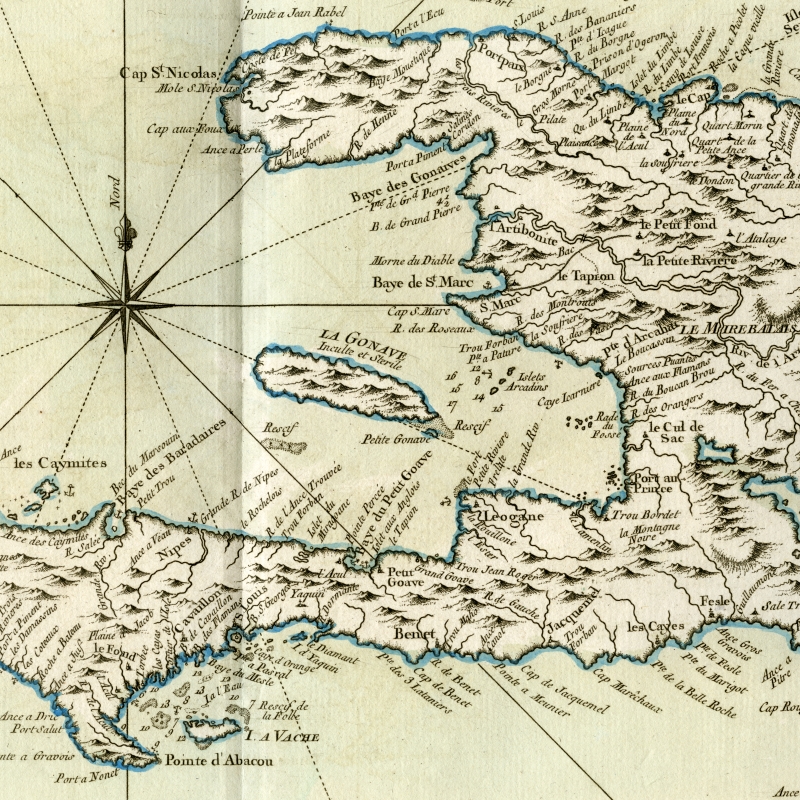

In addition to North America, I have also found evidence of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean, including Jamaica and Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti), who performed smallpox inoculations and likewise insisted that it was an ancient method in their homelands. The transatlantic and intra-American slave trades violently dispersed West African communities throughout the Americas so it is not surprising to find West Africans practising nearly identical forms of smallpox inoculation in different parts of the Americas. It is deeply troubling that despite ample early modern European sources and modern scholars’ efforts to acknowledge this history since the 1960s, the history of smallpox inoculation in sub-Saharan Africa remains understudied at best, or wholly unacknowledged at worst.

What types of strategies for survival did enslaved people deploy to cope with recurring smallpox epidemics?

While some enslaved West Africans used smallpox inoculation to prevent or contain epidemics, I have not found evidence that enslaved West Central Africans used smallpox inoculation before Europeans introduced it in the region. Instead, West Central Africans seem to have typically relied on topical remedies for smallpox symptoms. Many West and West Central Africans believed that diseases were consequences of troubled relationships with deities, spirits or ancestors. Some enslaved Africans’ healing rituals involved spiritual practices that appealed to divine or ancestral authorities.

Nevertheless, we must remember that enslavement was a brutal system in which enslaved people’s medical knowledge and authority over their or their kin’s medical treatment was rarely recognized by their enslavers. Enslaved people had to defend themselves against the risks associated with colonial public health and European and Euro-American responses to smallpox epidemics. This often took the form of refusing or resisting unfamiliar, risky or experimental medical treatments, warning one another about adverse experiences with overzealous medical practitioners, attempting to escape compulsory quarantines, and interceding on behalf of one another, especially young children.

As we have seen with COVID-19, epidemics disrupt normal societal functions and supply chains. One of the most terrifying and poignant things I’ve learned in my research about smallpox is that, despite the disease’s deadly potential, enslaved Africans tended to survive smallpox epidemics only to perish in larger numbers afterwards. Colonial officials frequently reported that, during and after smallpox outbreaks and epidemics, enslaved people died more from starvation, dysentery, parasitic infections, violence and insufficient supplies than from smallpox itself.

While some enslaved people fled to escape the epidemic, search for food and medicine, or bury their dead according to their traditions, many spent smallpox epidemics performing essential medical and public health labour. People of African descent had played a crucial role in enslaved and free people’s healthcare since the earliest days of European settlement in the Americas, managing public health in burgeoning settlements and urban and rural societies. Most of the hospitals, almshouses and pesthouses in the early modern Caribbean were built by enslaved Africans.

Spanish and Portuguese records concerning early modern smallpox outbreaks frequently describe enslaved and free people with African ancestry who worked as town criers and medical practitioners, such as surgeons and barbers. They provided local officials with updated information about the number and location of cases. This work often involved coming face to face with the nastiness of smallpox: foul stenches, open pustules, and feverish and delirious people who may have been trying to conceal infected parties in their homes.

Throughout the Caribbean region, most of the people who worked as laundresses, nurses, pharmacists, barbers, and in some cases, surgeons and doctors in almshouses, charitable hospitals, military barracks, lazarettos, and pesthouses were enslaved or free people with some African or Indigenous ancestry. One could say that between 1500 and 1800, they formed the vast majority of early modern Caribbean frontline public health workers, and like today’s frontline workers, they lost their lives at disproportionately high rates during smallpox epidemics.

In the context of rural and plantation slavery in the Caribbean, enslaved people played a crucial role as caregivers for their peers as they recovered from smallpox or smallpox inoculation. This often meant that someone, typically an older woman, would accompany one or more children or adults to a quarantine: a small house or makeshift hut separate from the typical plantation sickhouse or ‘hospital’. The enslaved caregiver would provide round-the-clock nursing, cooking, laundering, changing wound dressings, administering topical treatments, and notifying others about the health conditions of their charges.

By the late eighteenth century, it was relatively common for enslavers to hire one local medical practitioner, usually a free white man, to perform smallpox inoculations and prescribe smallpox treatments. However, the day-to-day labour of follow-up care typically fell on other enslaved people, providing some with opportunities to perform treatments according to their medical and healing epistemologies and pass on familiar treatments from trusted members of their communities. We should not assume, though, that enslaved people always trusted one another or wished to be treated in the ‘hospital’, as this left enslaved medical practitioners vulnerable to accusations of maleficence from their enslavers and European medical practitioners if the people under their charge did not survive.

What could the archives and library community do to increase the visibility of the role of Black people, so often hidden in the archives, and how can we facilitate research like yours?

‘Hiddenness’ brings to mind the ‘silences’ that the Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot describes in Silencing the Past. Trouillot identifies ‘the making of sources’, ‘the making of archives’, ‘the making of narratives’, and ‘the making of history’ or ‘retrospective significance’, as the four moments when ‘silences enter the process of historical production’. The silences surrounding Onesimus are produced at all four moments: his history is obscured in Mather’s records, the archives, our historical narratives, and our sense of his historical significance.

Likewise, focusing on Onesimus as an individual also risks silencing the collective history of his local community, who were, in Mather’s words, ‘an Army of Africans’ who all agreed on ‘one story’ about smallpox inoculation. Onesimus’s community was only one of many diasporic and West African communities in which smallpox inoculation was practised. Increasing Onesimus’s visibility, without further obscuring the untold numbers of West Africans who were also familiar with smallpox inoculation, requires rewriting the catalogue and Mather’s biography to reflect these histories. It also requires collaborating with other scholars and archivists to ensure that records bring the relationships between these sources to the fore.

Trouillot also reminds us that ‘not all silences are equal’ and they ‘cannot be addressed – or redressed – in the same manner’. The archival strategies that might be most effective for making Onesimus more prominent may not work as effectively for other Black people in your collections. More sustained collaborations with archivists, historians, Black Studies scholars and decolonial theorists, plus public historians who are working diligently on race, colonialism, archival representation and epistemology, can provide useful insights into how better to represent the histories obscured by the current structure and organisation of the Royal Society’s archives.

The geographic breadth of your collections makes them valuable to scholars who live abroad. Transnational archival research, already challenging to fund and undertake, is nearly impossible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digitising more of your collections would help scholars access them more easily. Likewise, supporting UK-based initiatives to increase the numbers of professors and archivists researching the intersections of Black history and the early modern history of medicine and science, as well as the number of Black professors and archivists working in research positions at UK institutions, would facilitate further research collaborations in these areas.

Table of people inoculated for smallpox by Charles Maitland between 1721 and 1723, from MS/245