Katherine Marshall looks at the first recorded descriptions of the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland, published in the 1690s in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

I’m currently cataloguing the early illustrative plates of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society for the Picture Library database. My recent research has led me down an unlikely path, to the myths and legends associated with a natural phenomenon.

I’ve always been keen to visit the Giant’s Causeway, but was unfamiliar with the fable from which it derives its name. Legend has it that the causeway was laid down by the giant Fionn Mac Cumhaill, forming a path across the North Channel to settle a score with the Scottish giant Benandonner. The tale was used to explain how the seemingly artificial structure of the stone columns came to be on the coast of Antrim, Northern Ireland.

The Giant's Causeway (image from Wikimedia Commons)

The first recorded description of the Giant’s Causeway came in a letter from Irish politician Sir Richard Bulkeley FRS to Martin Lister FRS on 24 April 1693, and published in issue 199 of the Philosophical Transactions. Having not visited the site himself, Bulkeley relied on an account from a Cambridge scholar who had made a special trip to see it the previous summer, accompanied by William King, Bishop of Derry (and subsequently FRS).

A follow-up to this enquiry was sent to the Society on 19 May 1694. It consisted of a further account by Samuel Foley, Bishop of Down and Conor, together with answers to Bulkeley’s queries on the causeway and comments by Irish physician Thomas Molyneux FRS (CLP/9i/46).

Molyneux was the first to assert that the causeway is a natural phenomenon or ‘natural curiosity’, saying that its identification as the workmanship of man had been ‘misguided, I suppose, chiefly by the Barbarous Name the Superstitious People of the Country have given it; who through Ignorance, do usually ascribe whatever is strange and extraordinary, though Natural, to the working of Giants, Fairies, Daemons, and such like Imaginary Causes.’

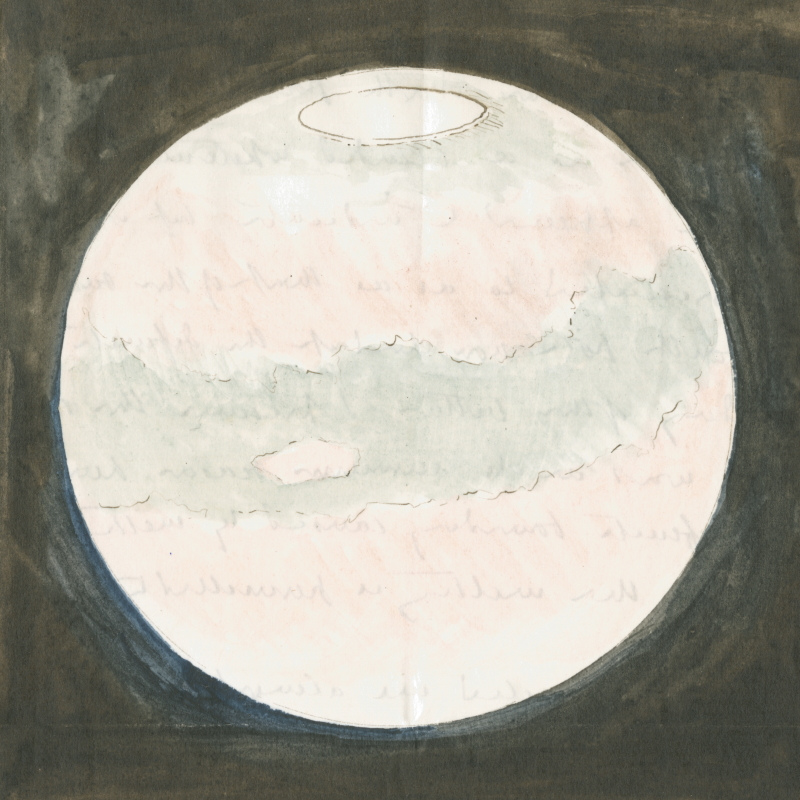

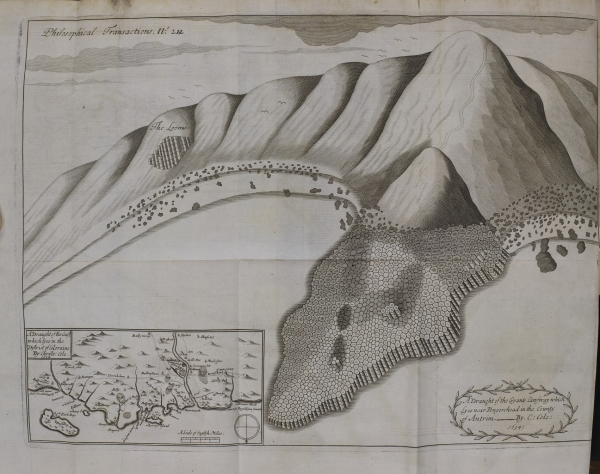

Published in Philosophical Transactions issue 212, the enquiry is annexed with the following map by Christopher Cole, described as a ‘Collector in those Parts’. His draught is a schematic depiction of the coastline with a distorted perspective. His decision not to draw the causeway as ‘a Prospect, nor as a Survey or Platform’ was intended to offer a clear view of the columns, which he placed at the centre of the composition. Perhaps his connection to the place and its folklore meant that Cole was disinclined to offer a more empirical representation.

Giant’s Causeway after Christopher Cole, 1694 (RS.19039)

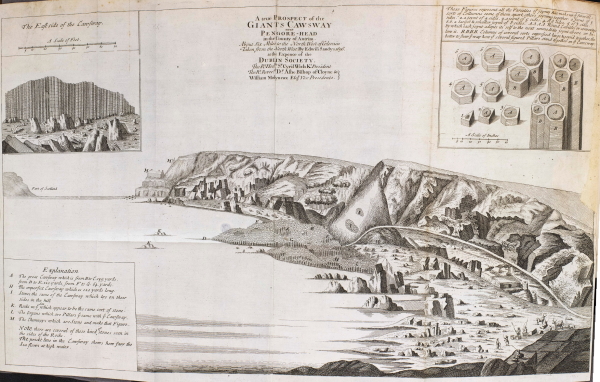

A correct draught of the causeway was ordered by the Dublin Philosophical Society and printed in Philosophical Transactions issue 235 as a standalone plate. This true prospect was completed by artist Edwin Sandys and is a more accomplished rendering, but for me it loses the sense of mystery that is captured in Cole’s earlier illustration.

‘A true prospect of the Giants Cawsway’ after Edwin Sandys, 1697 (RS.19054)

We now know, thanks to extensive research carried out by geologists since these early enquiries, that the famous headland consists of approximately 40,000 basalt columns extending four miles along the coast. The pillars are pentagonal, hexagonal or occasionally heptagonal in shape, and are closely packed together and vertically segmented. It was formed approximately 60 million years ago during a period of volcanic activity, when lava flowed into the sea, cooled rapidly, and contracted and fractured into the distinctive columns.

You can’t beat a good story, however, and the fable is still peddled to tourists visiting the UNESCO World Heritage site today. You can experience the full tale through this commissioned video by the National Trust, who have been the custodians since 1961. Meanwhile, with holiday plans on hold, I’ll have to satisfy myself with more stories from the Picture Library collections.