Looking forward to the Bank Holidays in May? You can thank a Fellow of the Royal Society for the concept.

It’s May next week, and our readers in the UK will know that May comes with two Bank Holiday Mondays. Hurrah! Let’s offer a vote of thanks to the politician who introduced the Bank Holidays Act 1871 – and did you know that he was also a Fellow of the Royal Society?

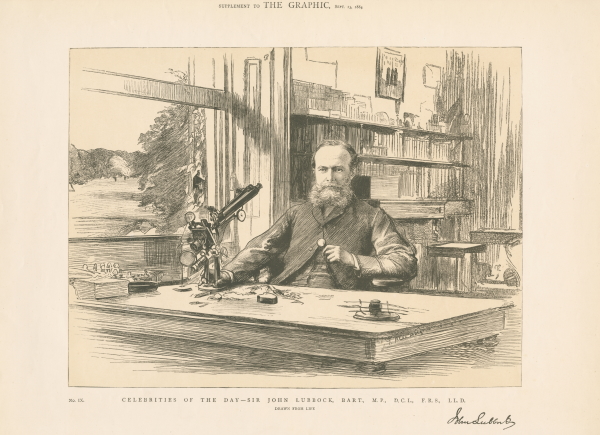

John Lubbock (1834-1913) was elected to the Fellowship at the tender age of 24, as ‘The Discover of many new species of British and Foreign Entomostraca’ (a historical subclass of crustaceans – yes, I did have to look that up). Family history would have been on his side, too – both his grandfather, Sir John (‘a gentleman very conversant with various branches of science’) and his father – surprise! – Sir John (‘a gentleman well versed in mathematics & various branches of natural philosophy’) were Fellows before him, as well as being heads of the Lubbock and Company bank.

In 1842, when John Lubbock was eight years old and living at High Elms, the family residence near Downe in Kent, a gentleman by the name of Charles Darwin moved into nearby Down House. Young John, who had been primed by his father to hear a ‘great piece of news’ and thought he was about to receive a new pony, was apparently rather underwhelmed at first. Darwin was to become a close friend and mentor, as shown by the titles of two biographies in our Library collections.

Photograph of an original Daguerreotype image taken by the Lubbocks’ governess, Mademoiselle Schwyer, showing the Lubbock family at High Elms. John Lubbock is the boy holding the cricket bat. Dated (by inference) summer 1843, making this one of the first outdoor Daguerreotypes taken in England. With thanks to the Lubbock family archive; not to be reproduced without permission.

Photograph of an original Daguerreotype image taken by the Lubbocks’ governess, Mademoiselle Schwyer, showing the Lubbock family at High Elms. John Lubbock is the boy holding the cricket bat. Dated (by inference) summer 1843, making this one of the first outdoor Daguerreotypes taken in England. With thanks to the Lubbock family archive; not to be reproduced without permission.

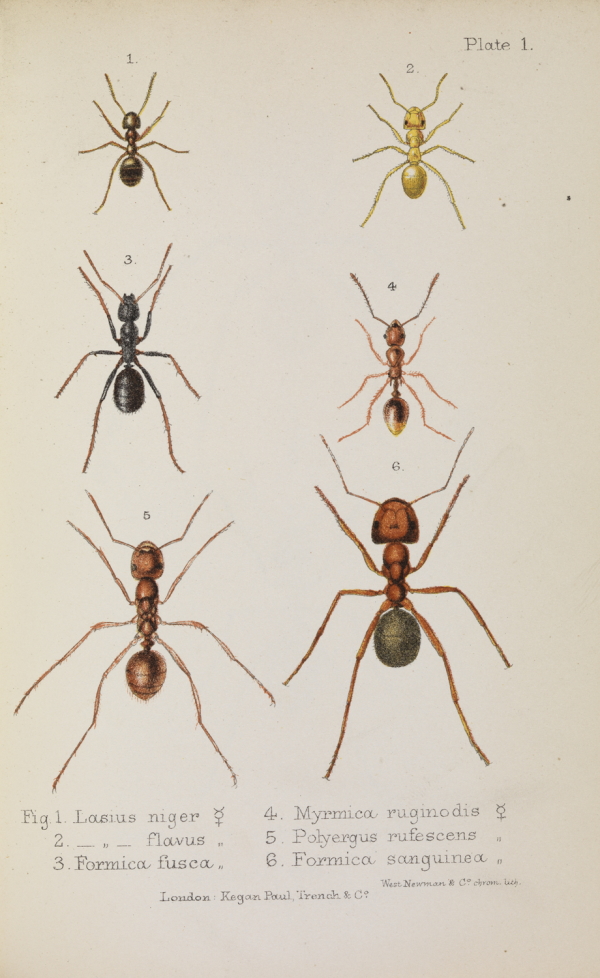

John Lubbock’s scientific work extended far beyond his early research on crustaceans. His first two published books, Pre-historic times (1865) and The origin of civilisation (1870), drew on his interests in archaeology, ethnology and evolutionary theory, and coined the terms ‘Palaeolithic’ and ‘Neolithic’. He was one of the founder members of the influential X Club, wrote extensively on botany, entomology and the social habits of insects and animals – a picture from his Ants, bees and wasps (first published in 1882, with many later editions) is shown below – and produced popular volumes aimed at the general reader, such as The beauties of nature and the wonders of the world we live in (1892). An extensive set of the natural history notebooks used in the preparation of these works is held in the Royal Society Library.

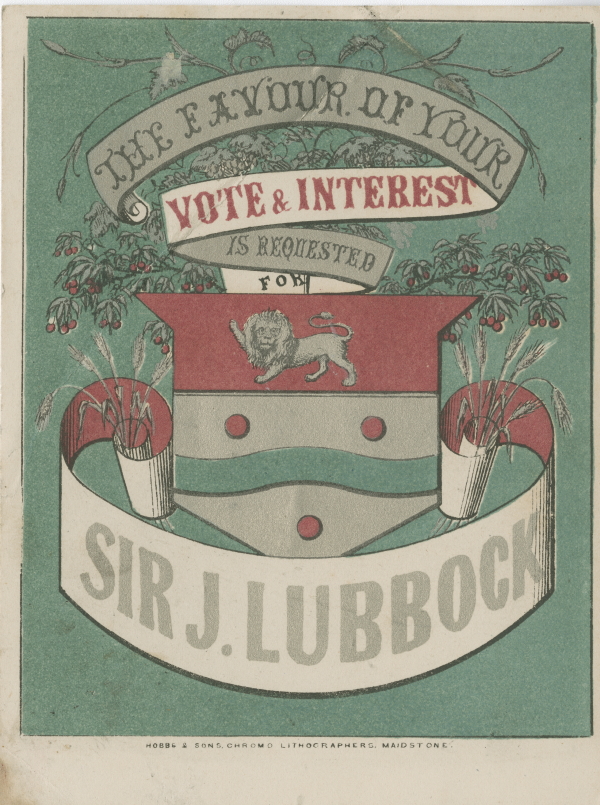

And that’s not all. In addition to his scientific interests and continued stewardship of the family business, the man described by Punch magazine as ‘The Banking Busy Bee’ was an active and influential politician. Elected to Parliament in 1870 as the Liberal MP for Maidstone, his agenda was strongly supportive of education and the study of science in primary and secondary schools. Our Lubbock archive includes this rather attractive postcard-sized election flyer requesting ‘The favour of your vote & interest … for Sir J. Lubbock’; it’s certainly classier than the literature coming through my letterbox in advance of the May local and mayoral elections:

One of Lubbock’s first successes as an MP was the aforementioned Bank Holidays Act of 1871. In addition to the long-recognised Christmas Day and Good Friday, the Act ensured that four days in the year would be official holidays: Easter Monday, Whit Monday, the first Monday in August, and 26 December. There have been additions and date changes since then, of course – our Early May and Spring Bank Holidays date back to the 1970s – but John Lubbock is the one who deserves our appreciation when we’re relaxing in the sunshine (or rain) next Monday.

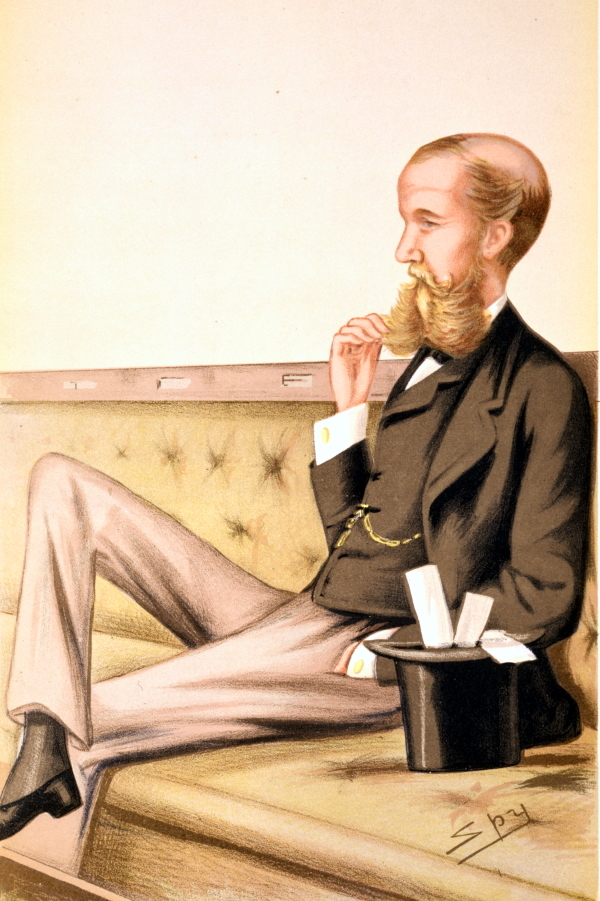

The new holidays were so popular in Victorian times that they were known for a while as ‘St Lubbock’s Days’. Well, maybe not universally popular: the accompanying text to the Spy cartoon shown below, published in Vanity Fair in 1878, says (rather snippily) that Lubbock:

‘has a tender love for flowers, children, wasps, clerks, and the rest of the smaller creation … though a man of much application, he has been made famous as ‘St. Lubbock’ for the Bank Holiday Bill, by which he endowed the country with four compulsory days of idleness a year and thus diminished the work without improving the morals of the community.’

The likely author of this text, Vanity Fair founder Thomas Gibson Bowles, later became a Conservative MP, so there may be a bit of political sniping involved. Lubbock is definitely a hero of mine, though, and if Bank Holidays, scientific education, support for the new ideas of Darwin, and the preservation of ancient monuments (resulting in the peerage bestowed on him in 1900 as 1st Baron Avebury of Avebury) are not enough, I’ll leave you with one of my favourite quotes, guaranteed to lift the heart of any librarian or library user. It’s from his 1887 book The pleasures of life, and says simply:

‘We may sit in our library and yet be in all quarters of the earth.’