Sandra Santos discovers how improvements in microscopes, and the invention of photomicrography, opened up a whole new world to scientists.

It’s curious to think how much of the world remained unknown before the invention of optical devices. In his introduction to The microscope and its revelations (1856), William Carpenter FRS wrote these inspiring lines:

‘The universe which the microscope brings under our ken, seems as unbounded in its limit as that whose remotest depths the telescope still vainly attempts to fathom. Wonders as great are disclosed in a speck, of whose minuteness the mind can scarcely form any distinct conception, as in the most mysterious of those nebulae, whose incalculable distance baffles our hopes of attaining a more minute knowledge of their constitution’.

In the 1820s, the invention of the achromatic microscope had overcome earlier problems with spherical and chromatic aberration and revolutionised the field. Lens and microscope manufacturers such as Karl Zeiss – who exhibited at the 1887 Royal Society conversazione – were then able to deliver the quality needed by scientists to observe a whole microscopic universe, hitherto significantly blurred and distorted. The ultimate frontier to the invisible was conquered, opening the doors to a microscopic view of the world now clearer and more defined than ever before.

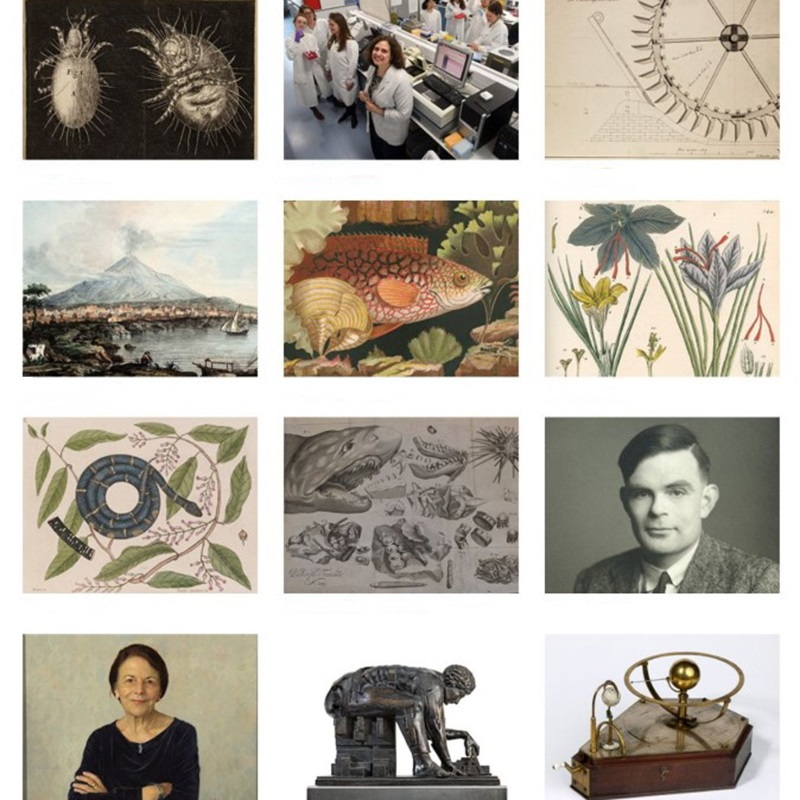

Powell and Lealand compound microscope. Thought to be the instrument awarded the prize for ‘best compound achromatic microscope’ in June 1843 by the Royal Society. R8460 © The Royal Society

The appeal of microscopy meant that it grew rapidly as a hobby, as well as being a tool for scientific work. Portable microscopes became a faithful companion for country walks. Plants were harvested and their forms and colours attentively inspected, and mineral fractures, layers, and shapes were analysed in minute detail. Artists were at the forefront of those inquisitive times, and the feeling that everything was within reach of the eye was inspiring and revolutionary.

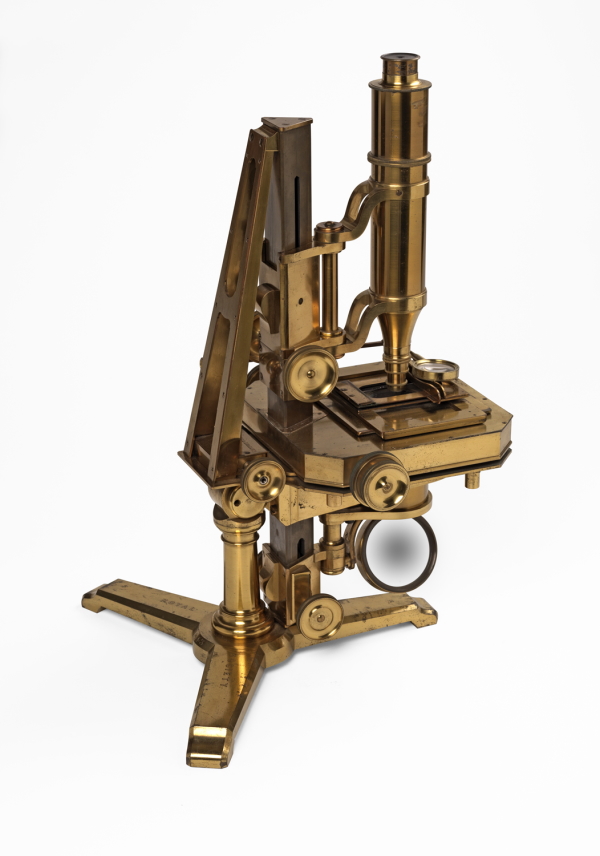

Plate from Haeckel's Die Radiolarien (Rhizopoda radiaria): eine Monographie: Atlas (1862). R9486 © The Royal Society

The impact of the resulting images on a completely new graphic vocabulary, extending to drawing, painting, design and photography, illustrates the symbiotic connection between science, art and the natural world. Examples range from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904) to Wilson Bentley’s micrographs of snowflakes, and from the cell-like shapes of Gustav Klimt – an avid attendee of microscopy lectures – to the early abstract experiments of photographer Laure Albin-Guillot with her Micrographie décorative (1931). In the centre of this emergent microcosmos, diatoms found a bright spotlight.

Nicknamed ‘glass houses’ or ‘jewels of the sea’ because of their hard, translucent silica shells, these single-cell microalgae are responsible for producing a significant proportion of the Earth’s oxygen. Ethereal wonders of the microscopic realm, their intricate patterns and lines captivated the attention of scientists and also of artists, finally able to see these extraordinary shapes which had previously been hidden by their minute scale.

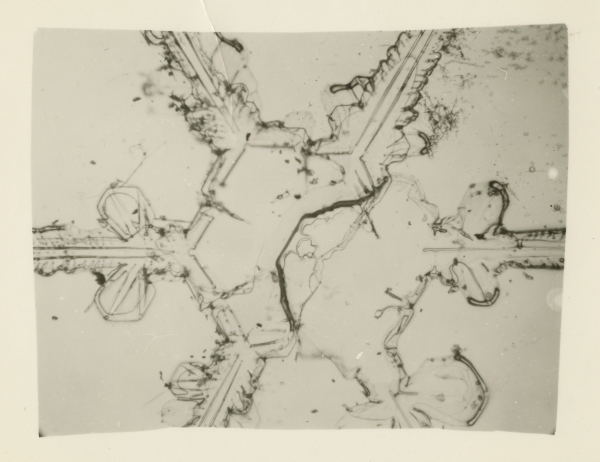

The rise of photomicrography, pioneered by Richard Leach Maddox, would bring the once invisible even closer to a growing Victorian audience. Diatoms were the stars of early photomicrographs and retained their appeal into the twentieth century. These ‘beautiful structures’, as Maddox described them, were a recurring presence in the numerous exhibitions and prizes of the Royal Photographic Society, where they often appeared in delicately staged compositions.

We also find them in the programme for the 1909 Royal Society conversazione which included a ‘Photomicrograph showing abnormal striation of the diatom Navicula lyra, by Mr. W. Bagshaw’, most probably Walter Bagshaw, author of Elementary photo-micrography (1902). Through the work of illustrious figures such as Bagshaw, George H. Rodman and Edwin Edser, photomicrographs featured in many Royal Society Conversazioni, especially in the 1910s and 1920s.

Inspirational, scientific, or both: whether of diatoms, leaves, pollen, or the wings of insects, a micrograph always makes me think of the development of optics and the microscope as the ultimate bridge to forms of life otherwise unseen, knowledge otherwise unknown.

It makes me wonder, what else remains hidden?

Photomicrograph showing a snow crystal from Halley Bay, Antarctica, 1956. R12110 © The Royal Society

Photomicrograph showing a snow crystal from Halley Bay, Antarctica, 1956. R12110 © The Royal Society