Keith Moore takes a look at current citizen science projects such as the Big Butterfly Count, and finds some beautiful depictions of butterflies in the collections of the Royal Society.

Being confined to home for large parts of the past year and taking long walks in local parks and gardens has made amateur naturalists of many of us. Now that brighter weather is here at last, perhaps we can trade this pandemic response into some citizen science? There are lots of observational and counting projects out there, just a click away.

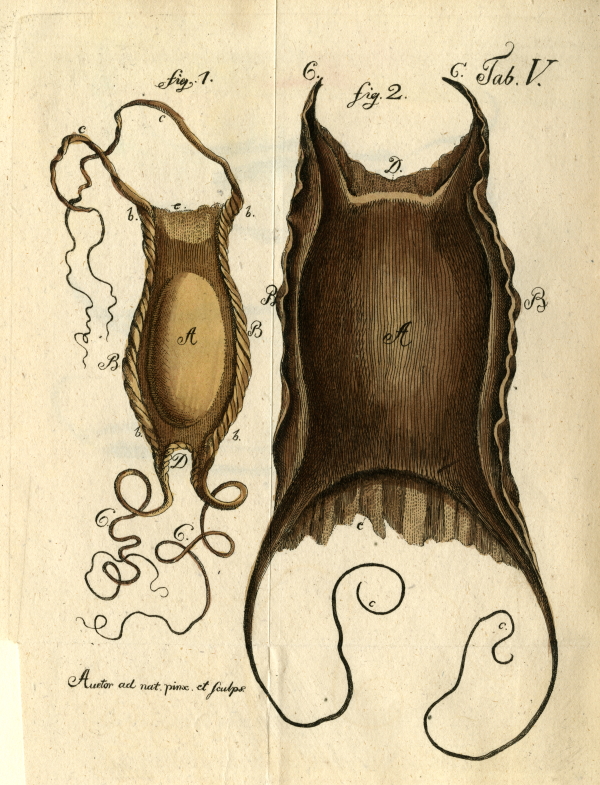

Purse snatcher: marine egg-cases, by W.G.T. von Tilenau, 1802 (RS.11837)

One of my favourites, because it involves a bit of collecting by the seaside, is the Great Eggcase Hunt, which aims to record mermaid’s purses, the residue of shark and ray breeding. If you happen across an egg-case on the beach, it’s quick to take a snap and try to name that shark, with an easy identification guide. There is something curiously satisfying about detecting a species without seeing the original creature. Another summer perennial is the Big Butterfly Count, where you do get to see the insects in question. If you try it, you’ll be in good company: scientists have been recording such things for centuries.

There was an original group of butterfly-hunters, known as the Society of Aurelians, which was active in London during the early to mid-eighteenth century. Accounts of the organisation are mostly lost, the result of a tavern fire in 1748 that caused the destruction of its records and collections. The Royal Society’s then-Librarian, Emanuel Mendes da Costa FRS (1717-1791) appears to have been a member of the group, but the main legacy was Moses Harris’s great book of entomology, The Aurelian, or a natural history of British insects (1766). Da Costa wasn’t the only Librarian with solidly entomological interests: I’m always amused to be reminded that my predecessor, the hymenoptera specialist William Edward Shuckard (1803-1868), was fired by the Royal Society for being ‘too interested in science’ – those bugs were just too fascinating.

Scale drawing: nine specimens of butterfly wing scales, by Adam Winterschmidt, c.1764 (RS.11805)

I don’t doubt that Shuckard browsed the Society’s shelves for works on insects, therefore. The Society’s collections contain many works where the plates are just as beautiful as their models. I’m particularly fond of microscope studies by a contemporary of the Aurelians, Martin Ledermuller (1719-1769). His Amusement microscopique (1764-75) contain some wonderfully abstract-looking and acid-tinted details of insect anatomy: rather lovely, but not much use as a field guide of course.

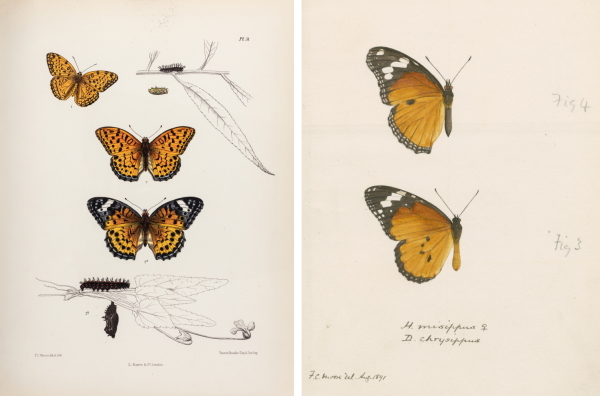

Among the best butterfly artists around were the Moore family – not mine, I’m sorry to say – but the father and son team of Frederic and Frederic C. Moore. Moore père (1830-1907) was employed by the East India Company’s London museum, and compiled the vast Lepidoptera Indica (1890-1913), which attempted to catalogue the butterflies of the Indian subcontinent. His son, F.C. Moore, proved to be an able illustrator and contributed many fine plates to his father’s work. Happily, he also found time to produce original watercolours for others, and the Society owns several of his figures in manuscript, made for Charles Swinhoe (1838-1923).

F.C. Moore’s butterflies, printed and original, 1881 and 1891 (RS.14185 and RS.11676)

Following an army career in India, and the inevitable large-scale tiger-shooting, Swinhoe retired to dedicate himself to entomology, completing the Indica volumes after Frederic Moore’s death. Swinhoe’s 1893 paper for the Royal Society’s Proceedings, on mimicry in butterflies, contains some wonderful studies of a variety of similarly evolved adult insects in their finery, and it’s interesting to compare engraved versions of Moore’s work with their pristine hand-made equivalents.

Now you may not rise to the heights of nature study and artistry shown by some of these naturalists: but if you have a camera or a phone, or if you have a little time to be a good spotter – do take part in one or other of the many science record-building sessions lined up for the summer – you too can be an Aurelian, or find new value in an old purse.