Virginia Mills ventures out to Dulwich Picture Gallery to see their exhibition on the story of plant photography.

I recently ventured out to Dulwich Picture Gallery to see their exhibition Unearthed: Photography’s Roots. This was my first in-person visit to an art show for many months, and while galleries have provided some incredible online visitor experiences during lockdown, I can’t deny it was nice to be out and about on the culture trail again.

Unearthed tells the story of nature photography, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, through images of plants. Having previously worked at Kew Gardens Library, Art and Archives the subject matter appealed to me, but I also had a secondary motive as the exhibition features several items from the Royal Society’s own collections, including cyanotypes by Anna Atkins and manuscript material from John Herschel and William Henry Fox Talbot.

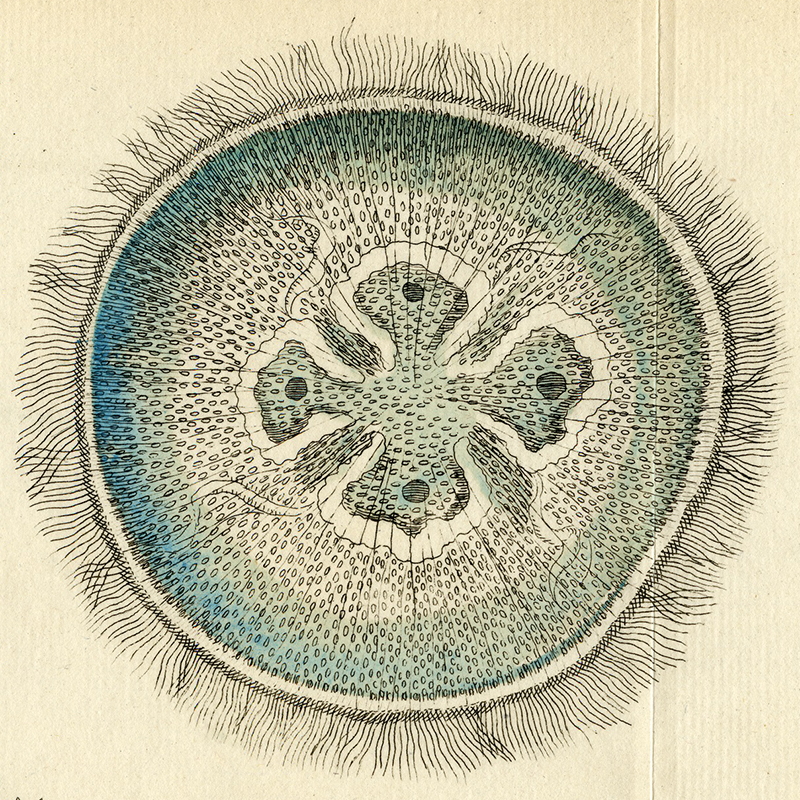

Cyanotype image of a fern by John Herschel, 1848 (HS/1/366)

No look at the development of plant portraiture would be complete without featuring Anna Atkins. Indeed, no narrative on the development of photography should omit her, as the self-published work Photographs of British algae: cyanotype impressions (1843-1853) was the first book to be illustrated with photographic images. You can find out more about Anna in our earlier blogpost commemorating her 222nd birthday; suffice to say here that the non-camera photographic process that created these striking Prussian blue photograms meant they were not reproduceable through a negative or plate as was possible with later forms of camera photography. Each cyanotype is unique, so although Atkins produced around 12 copies of her British algae, no two are exactly the same.

It was a particular treat then to see the Atkins volumes from the Royal Society collections alongside those from other institutions, including the Horniman Museum. Anna distributed copies of British algae to various scientific and cultural institutions, and each of the recipients bound the sewn sections together into volumes, so every volume is as unique as the prints in it. The image below shows Anna’s Dictyota dichotoma from our volume 1, which you can view in full on the Royal Society website using Turning the Pages technology. Many other institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Natural History Museum, the Science Museum and the New York Public Library have put images of their copies online if you fancy comparing some.

Unearthed is an interesting exploration of the interplay between art, science and photography, making comparisons between photographic images of plants and the painted still life tradition as well as the dual functions of photography as art and documentation. The exhibition makes much of the significance of photography for botanical science in terms of accurate representation of plants through a more objective medium. It struck me that what was not present, perhaps understandably for a photography-centred exhibition, was much comparison with other forms of scientific representation of plants.

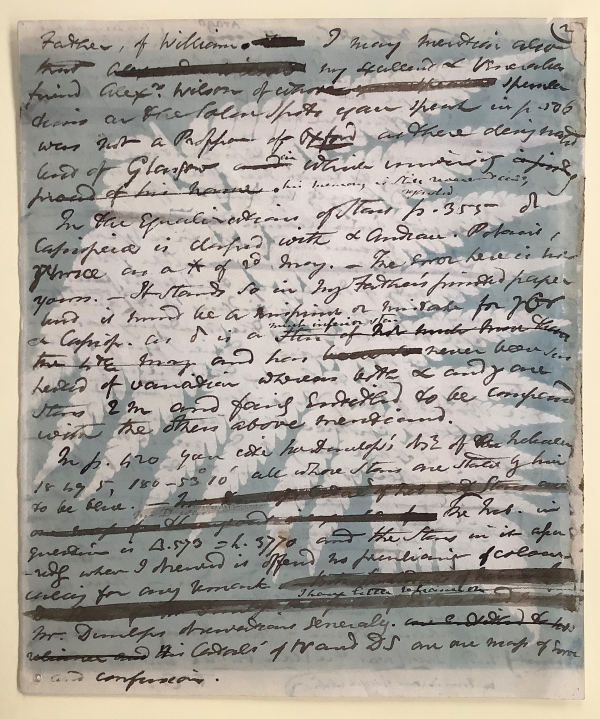

For example, Anna Atkins’s blue silhouettes owe a visual debt to the age-old practice of nature printing. Below is a seventeenth-century example from the Royal Society collection, in the form of an oak leaf inked up and transferred to paper by early microscopist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek FRS. He used this print as a scientific tool to show from where, on the exact leaf he used, he took the material examined under his microscope, labelling the enlarged image and the nature print with corresponding letters.

From a letter from Leeuwenhoek to Royal Society Secretary Henry Oldenburg, Delft, 26 March 1675 (EL/L1/13)

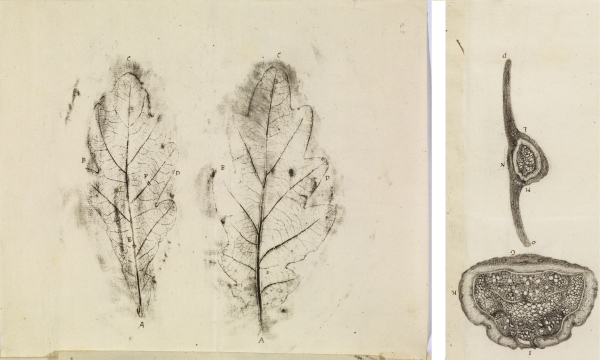

In the collections of the Royal Society we can also see that botanical illustration continued to sit alongside the use of photography as an important tool, as with the illustration below from 1862, the height of Victorian ‘fern mania’. Ten years after Anna Atkins followed up her algae cyanotype book with one on British ferns, William Hooker FRS still chose to illustrate his fern work with traditional botanical illustrations as did most other botanists.

Didymochlaena lunata, lithograph by Walter Hood Fitch, from Garden ferns by William Hooker, 1862

Didymochlaena lunata, lithograph by Walter Hood Fitch, from Garden ferns by William Hooker, 1862

Indeed, botanical illustration persists in a scientific as well as an artistic capacity to this day. When new plant species are described, the written description will feature alongside a hand-drawn illustration – but why is this, if the camera can give us a perfect objective reproduction? It’s because the illustrator can capture a composite of all the typical, defining features of a species which may not always appear in a single specimen. They can also show dissections of the plant clearly delineated, and different states of development – fruit, flower and seed – all in one image, to help the amateur or professional botanist with identification.

It will be interesting to see if photography does come to supplant this as the technology continues to advance. Dulwich featured a rose still-life by Nick Knight. The image is a composite, generated from a mobile phone photograph combined with data from similar images, harvested using artificial intelligence. The data is then used to enhance low-resolution areas on the original photograph, as you can see in this fascinating video, Roses from my Garden. The result is an image of such smooth clarity that it actually looks painterly. Knight’s roses are still-life compositions and his AI uses combinations of images that have had different filters applied.

As I read about the process, I wondered if a similar technology could be applied to the creation of a scientific representation for identification purposes. Not as a type, where the use of images in place of a specimen or description of a specific biological individual is controversial (see this article, for example), but following in the tradition of the idealised drawn exemplar to aid identification, by creating a composite of many views of the same species. Perhaps some botanists would be horrified by this: in the nineteenth century, as photography was blooming, some still wanted neither photograph or illustration to augment their work. Returning to the theme of ferns (the Victorians really loved them), naturalist Marian Ridley proclaimed in her Pocket guide to British ferns (1881) that:

‘I have purposely refrained from introducing in this work any drawings, because it is of such importance to consult the real fronds. Plates are a great help when it is impossible to procure the ferns themselves; but they never do and never will, however beautifully and accurately printed, answer the same purpose.’

I am sure there are many contemporary botanists who embrace the full possibilities of photographic technology in many ways – I’m thinking for example of those apps that can identify unexpected blooms in your garden from a snapshot – but such were my amateur musings as I gazed at Knight’s roses.

The contradiction exposed by Unearthed is that photography is lauded for being objective but in truth it never is: the image-maker, camera or other technology are always intermediaries, adding layers of interpretation. This is explored in the Dulwich exhibition in a beautiful video installation, On Reflection by Ori Gersht, which presents an image of a flower arrangement which is revealed to be a reflection in a mirror as it shatters. What’s more, they were not real flowers but artificial, reminding us that photographs and film can play with our perceptions with more subtlety and guile than perhaps any other art form.

As we emerge from an unprecedented period of only speaking to our friends, family and colleagues through a screen and seeing art online, this exhibition reminded me – in more ways than one – that sometimes there really is no substitute for the real thing.

Unearthed: Photography’s Roots is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 30 August.