Virginia Mills highlights the contrast between the field-observation practices of naturalist Gilbert White and the specimen-based approach of John Gould FRS.

These days, we’re accustomed to observing wildlife behaviour on our TV screens and having it explained to us, often in the dulcet tones of David Attenborough FRS. But have you ever considered that seeing nature in the field was not always the way naturalists worked, and we once had to be taught this ‘way of looking’?

Taking birds as my historical battlefield, I’m pitting a twitcher against a taxidermist to illustrate different methodologies in zoology, using examples held in the Royal Society library and archive. I’ll be contrasting the field-observation practices of pioneering naturalist Gilbert White with the specimen-based morphological approach of the Zoological Society’s first taxidermist, John Gould FRS.

The eighteenth century saw increasing European Imperial expansion, with sea voyages taking naturalists to many points of the globe. Often, the specimen work of such natural historians was carried out at one remove: examination might be in the relative comfort of a ship’s cabin, or in the faraway home of a natural philosopher or learned society.

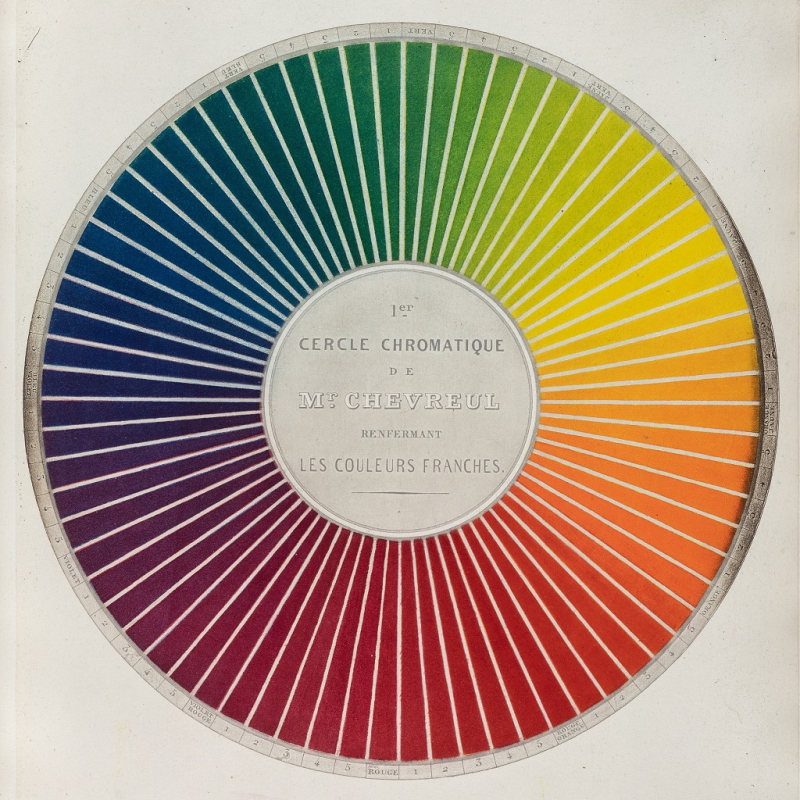

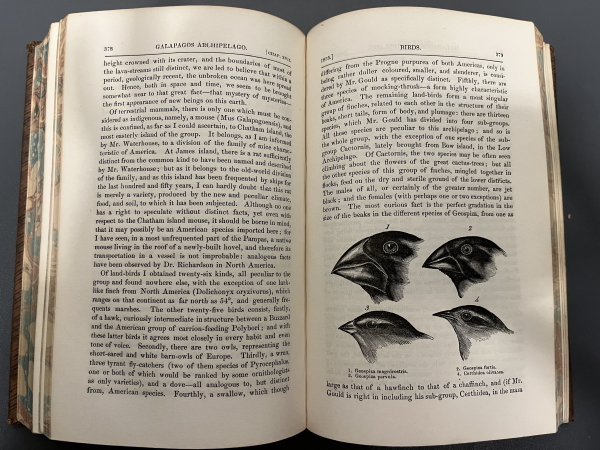

John Gould followed this model when, in 1827, he started as a curator and preserver at the museum of the Zoological Society of London. From his acquaintance with the specimens he prepared, he became an expert in the identification of species, particularly birds, by doing detailed close-up examinations and noting subtle but important differences. Most famously, he identified Charles Darwin’s Galápagos finches as a formerly unknown group comprised of numerous separate but closely related species.

Darwin’s Galápagos finches. Source: RCN 35340

Gould was often amongst the first to see collections sent back from expeditions, and made his fortune from publishing beautifully illustrated compendiums of these exotic species from across the expanding British Empire. His bird books, the earliest of which were illustrated by his wife Elizabeth using stuffed specimens and rough sketches prepared by her husband, became objects of desire for wealthy Victorian collectors, and remain items of great beauty. They are also an important historical record of biodiversity, but equally they are artefacts created by a violent imperial expansion and a harbinger of biodiversity loss.

Lophophorus impejanus (Impeyan pheasant) by Elizabeth Gould, from A Century of birds from the Himalaya mountains (1832), RCN 41609

Lophophorus impejanus (Impeyan pheasant) by Elizabeth Gould, from A Century of birds from the Himalaya mountains (1832), RCN 41609

Gould made only one voyage of exploration in person. To give him his due, on this trip to Australia he did his fair share of twitching, and he clearly had a sense of appreciation for the unparalleled experience of seeing birds living in their natural environment:

‘The Rose-breasted Cockatoo possesses considerable power of wing, and … frequently passes in flocks over the plains with a long sweeping flight, the group at one minute displaying their beautiful silvery grey backs to the gaze of the spectator, and at the next by a simultaneous change of position bringing their rich rosy breasts into view, the effect of which is so beautiful to behold, that it is a source of regret to me that my readers cannot participate in the pleasure I have derived from the sight.’ (Birds of Australia, volume 5, plate 4).

Though he has an evident love of birds and is interested in describing their behaviour for his readers and the scientific record, primacy is still placed on the examination of specimens for the ultimate purpose of classification. In Birds of Australia he reports that, to be sure of his identification of the Adelaide parakeet as a distinct species (Platycercus Adelaidiae), he killed over 100 birds in various stages of plumage and development.

Platycercus Adelaidiae, from Birds of Australia, volume 5 plate 22

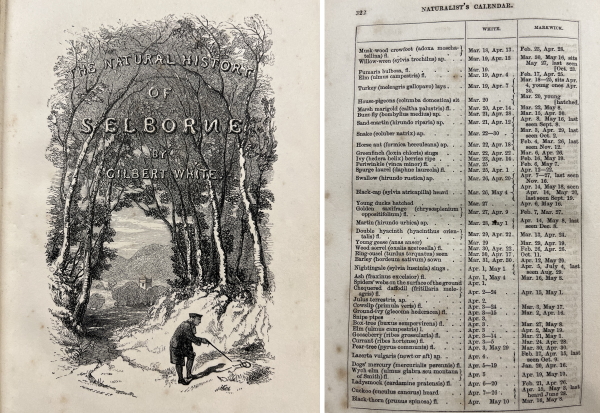

The Reverend Gilbert White, my foil for Gould, may not have ‘discovered’ or identified as many new species of bird, and his most famous work The natural history of Selborne (1789) was not as large, showy or immediately lucrative as Gould’s volumes. It is, however, one of the few books never out of print since it was first published, and its most important legacy is not necessarily the observations of Selborne wildlife but the method nascently codified in White’s accounts.

Title page and calendar from The natural history of Selborne

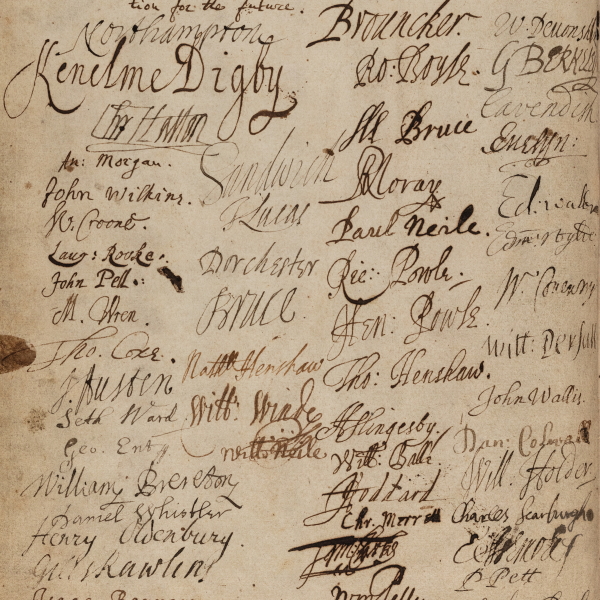

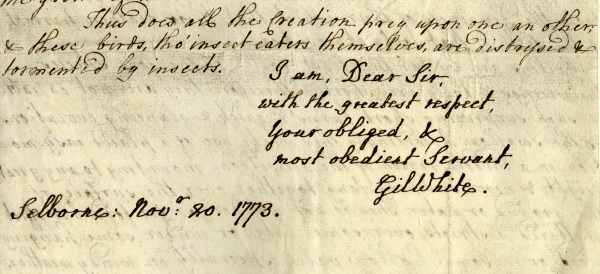

The book is edited from letters White sent to other naturalists, some published in the Philosophical Transactions, sharing observations of his parish in Hampshire. One such correspondent was Daines Barrington FRS, with whom he discussed Hirundinidae: swallows, swifts and martins whose migratory return to Selborne he logged year after year. His letters to Barrington, originals held in the archive of the Royal Society, show White as an acute observer of behaviour. His charming delivery, alongside the validity of his observational practice, has no doubt contributed to the enduring popularity of his writing. Take this passage on the house martin’s engineering prowess:

‘The crust or shell of this nest seems to be formed of such dirt as comes most readily to hand, & is tempered & wrought together with little bits of broken straws to render it tough & tenacious … But then that this work may not, while it is soft & green, pull itself down by it’s own weight, the provident architect has prudence & forbearance enough not to advance it’s works too fast; but by building only in the morning, & by dedicating the rest of the day to food, & amusement, gives it sufficient time to dry & harden.’

Letter from Gilbert White to Daines Barrington, 20 Nov 1773, L&P/6/27. Available as a digital version and a Philosophical Transactions article

As well as his letters, White kept meticulous journals in which he recorded his observations of fauna and flora, noting these alongside the weather, the activity of local farmers and other seasonal changes. He remained in Selborne all his life, building up a detailed picture of the seasons and the years. He knew when and where the swallows and house martins would return, making connections with his other observations that helped him understand why. Though he never solved to his satisfaction the question of whether the Hirundinidae migrated or hibernated, he was able to link their reappearance with the warming of the weather, and an increase in the number of insects, which he had seen the birds feeding on.

White used his other senses too, ‘looking’ not just with his eyes but with his ears. One of his oft-quoted discoveries is the differentiation of what was known as the willow wren into three separate species based on their different songs. Now I’d call that almost a knockout punch for field observation against dissection: after all, dead birds don’t sing.

Gilbert White is sometimes called a father of ecology. Most naturalists have probably heard of him, and even if they haven’t realised it, his methodology of watching and recording in the field is ingrained in modern ecological practice. The importance of observing animals in their environment, alongside morphological examination, is underlined if we return to the famous Galápagos finches. Identified by Gould as separate species from his examination of specimens in London, the full significance of this information can only be realised when paired with the observation that each one came from a different island and that each distinguishing characteristic made it better suited to its specific environment. It was this connected evidence that supported Darwin’s view of natural selection.

Nature documentaries are fabulous and educational, but let’s remember what many of us re-learned whilst locked down on our local patch: the benefits of being out in nature are many and there is plenty to discover and observe on your doorstep. For rainy days we’ve also prepared a gallery of ornithological illustrations from the Royal Society collections, so you can browse more Gould and discover other ornithologists’ work.