A new replication study in Royal Society Open Science revisits animal domestication research from the 1960s and 70s.

Royal Society Open Science has published its first non-psychology replication study: Cranial volume and palate length of cats, Felis spp., under domestication, hybridisation and in wild populations. Here, first author Raffaela Lesch tells us about the work.

What is the research about?

The core aspect of our research was to replicate a cornerstone result in the field of domestication research. Reduced brain size is one of the most consistent, yet hard to explain, features seen in domestic animals, compared to their wild ancestors. We set out to replicate studies by Paul Schauenberg in 1969 and Helmut Hemmer in 1972 on brain size in cats. Our goal was to evaluate if these previously reported results, of smaller brains in domestic cats compared to wildcats, would still hold up on a data set assembled and curated using today’s scientific knowledge.

Why were you interested in the research question and why replicate an earlier study?

The field of domestication research is moving fairly fast at the moment. Many or most of the hypotheses with the potential to offer a unifying explanation of the “domestication syndrome” (e.g., floppy ears, white fur patches, smaller brains, shorter snouts) are at least partially based on old literature. Much of the literature that compares wild and domestic animals is difficult to access, or may have methodological issues. We have to put effort into replicating old findings to further the field of domestication research and to see whether hypotheses, like the neural crest/domestication syndrome hypothesis of Wilkins and colleagues, are built on a solid foundation.

What is significant about your findings?

We found that domestic cats experience a reduction in brain size compared to their ancestor species, the North African wildcat. Hybrids of domestic cats and European wildcats have brain volumes that cluster between those of their parent species. Overall, our results concerning brain size in cats confirm the findings of the previous studies. Additionally, we also looked into a potential reduction of snout length, which is another common characteristic described in the context of the “domestication syndrome”. However, our data did not indicate a reduction in snout length in domestic cats; domestication does not seem to have affected snout length in cats.

What are the next research steps?

The next steps would be to continue replicating these old studies, not only for cats, but across other domestic species. Including additional new measurements into the workflow of replicating old results might also provide additional valuable insights.

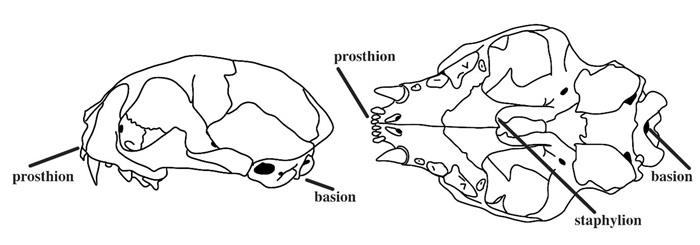

Fig 1. Lateral and ventral views of a cat skull indicating the landmarks used for measurements of palate length and basal skull length. Basal skull length was measured from prosthion to basion and palate length was measured from prosthion to staphylion.

Why did you opt to use the Replication workflow rather than submit a regular research paper?

We decided to use the replication workflow because it provides the opportunity of having our work reviewed in two parts. In our opinion, splitting the process in two is important for moving scientific publishing forward. If reviewers agree that the reasoning in the introduction and methods are sound, the paper passes the first review step. This means that independent of results the paper will be published as long as the outlined methodology is followed and the conclusions drawn are supported by the data. This process avoids the common phenomenon of not publishing null results and can help reveal weaknesses in previous research that might not otherwise be revealed. This is especially important for early career researchers (like myself), who are under enormous pressure to publish and options like the Replication workflow help alleviate the stress of how to deal with null results, if they are found.

Why is it important to replicate existing studies?

In the context of domestication research, it is crucial to replicate these older studies since they are the foundation to many currently debated hypotheses. This also holds true in the bigger picture of science. To counteract factors leading to the replication crisis, especially in historical studies, we have to put effort into establishing that our basic findings are solid and replicable. Replications sometimes seem to have the reputation of being boring, simple, and not requiring a lot of skill. I wholeheartedly disagree. Replicating an old study, while embedding and viewing it through the lens of today’s knowledge, was a lot more intriguing and challenging than one might think at first. Staying true to an actual replication, while at the same time adapting the study to current scientific standards, was an interesting experience.

Why did you choose to submit to Royal Society Open Science?

The concept of Open Science is not only a valuable tool, but a core aspect in making science more accessible and transparent. Making code, data, and resource material publicly accessible to anyone who is interested will ultimately be beneficial to us all. Prioritising transparency and open access will allow anyone to go back and look at the underlying data, code, review process and any step between.

What worked well during the peer review process?

Editors Professor Chris Chambers and Andrew Dunn were very kind when I first approached them and asked if RSOS would be interested in a replication study of this type. Prior to this manuscript RSOS offered the replication study article type for selected topics/journals. Both Editors Chambers and Dunn were incredibly open minded and encouraging about expanding this type of article to more fields and topics. Since replication articles are submitted in two parts (first introduction and methods are reviewed, followed by results and discussion), the reviewers had to review the manuscript in two steps. Both reviewers were very kind to commit to review both parts and provided insightful comments in both review steps, which decisively contributed to improving our manuscript.

Interested in submitting a replication study? Visit our website for further information and to view all previous Replication studies.

Image credits:

1. Cat skull in front of a black background, by Raffaela Lesch.

2. Figure 1 from Cranial volume and palate length of cats, Felis spp., under domestication, hybridisation and in wild populations.