Victorian artist George Frederick Watts painted a series of frescoes in number 7 Carlton House Terrace, now home to the Royal Society - but where are they now? Katherine Marshall investigates.

As I venture back into central London, I’m reminded of how lucky I am to work in such a magnificent building. As part of the Library team, a little background knowledge on its history is an important part of the job.

One story that has always interested me is that the reception room of number 7 Carlton House Terrace used to feature a number of murals painted by the Victorian symbolist artist George Frederick Watts. Being familiar with his more famous works, including Hope, the blindfolded woman seated atop a globe and trying to extract a tune from a single stringed lyre, I was naturally curious about what happened to these paintings.

Commissioned by George IV, Carlton House Terrace was intended to provide accommodation for the well-to-do and generate income for the King, whose lavish lifestyle and appetite for improving property had seen him running up debt renovating Carlton House, his former palace as Prince Regent, and then Buckingham Palace on his accession to the throne. Carlton House was demolished and the new town housing, designed primarily by the Regency architect John Nash in classical style, was constructed on the same site between 1827 and 1832.

‘Carlton House Terrace & Duke of York’s Column, from St. James’s Park’, engraved by Allan [?] after a watercolour by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1793-1864), ca. late nineteenth century.

‘Carlton House Terrace & Duke of York’s Column, from St. James’s Park’, engraved by Allan [?] after a watercolour by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (1793-1864), ca. late nineteenth century.

The dwellings now occupied by the Society have been home to a number of ‘first class’ residents – here’s a full list by former deputy librarian Alan J Clark in our Notes and Records journal. Of particular interest here is the occupant of number 7 from 1854 to 1855, the Conservative politician Lord Somers (Charles Somers-Cocks, 3rd Earl Somers). It was during his short lease on the Terrace that the Watts frescoes were commissioned and painted, a project which arose from the friendship between Lady Virginia, the wife of Lord Somers, and the artist.

Virginia was one of the seven Pattle sisters, which included the innovative photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, Sara Prinsep, and Maria Jackson, grandmother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell. Watts was closely associated with the celebrated Pattle family and even secured for Sara and her husband Henry Thoby Prinsep the tenure of Little Holland House, which would become their salon and where Watts himself would live for over 20 years.

The cycle of frescoes painted in the Somers’s dining room consisted of nine separate murals, each an allegorical representation of the material world: earth, water, wind, fire and air. The nine, which became known collectively as ‘The Elements’, featured representations from classical mythology, and the style was heavily influenced by painters of the High Renaissance, following on from the time Watts spent in Italy.

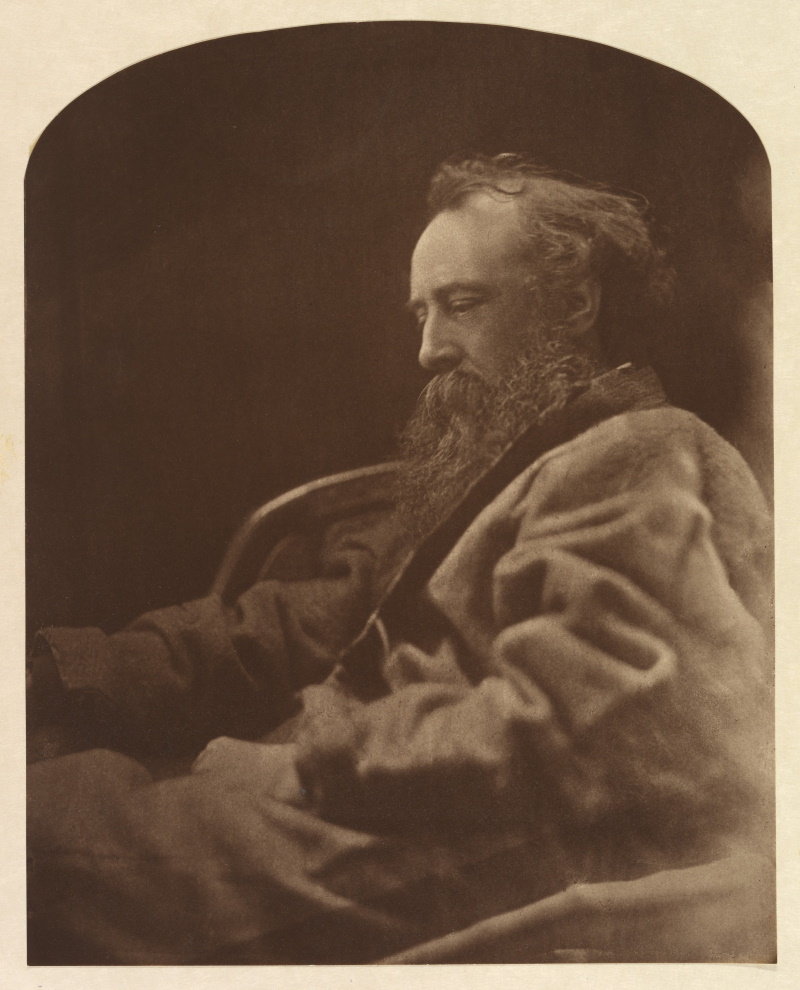

George Frederic Watts 1864, printed ca.1905, by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949. Met Museum. Open Access, Public Domain.

George Frederic Watts 1864, printed ca.1905, by Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949. Met Museum. Open Access, Public Domain.

Watts expert Nicholas Tromans published his research on the works in his essay ‘The Elements’: a fresco cycle by George Frederic Watts (2016), which includes interesting documentation on the fate of the artworks. It seems the paintings were covered over in the early twentieth century, with five being rediscovered in 1927, prompted by enquiries from Watts’s old friend and fellow artist Alfred Gilbert. Having been painted on royal property, the Crown Commissioner took over their care and oversaw their restoration. The remaining four were later discovered during the tenancy of the German Embassy in the mid-1930s.

Carlton House Terrace then fell empty after World War II, and it wasn’t until the 1960s that it was decided to hand over the use of the buildings to learned societies. The Royal Society’s move to the Terrace began in 1963, leading to the decision to remove the frescoes as the remodelling of numbers 6-9 began.

The five main frescoes of The Elements had to be restored once more after inadequate storage had left them in poor condition, and they were then loaned by the Crown Estate to Eastnor Castle (owned by relatives of the Somers family) in the 1970s, before being transferred to Malvern College in 1991, where they remain today. Malvern College has generously provided me with photographs of the murals in situ, and it’s exciting to finally see the artworks in full colour. I’m delighted to be able to share a glimpse of these rarely seen works by Watts, with kind permission of the College:

Wind and water frescoes by George Frederick Watts, 1854-5. Photographs courtesy of Malvern College, 2022.

Wind and water frescoes by George Frederick Watts, 1854-5. Photographs courtesy of Malvern College, 2022.

Earth fresco by George Frederick Watts, 1854-5. Photograph courtesy of Malvern College, 2022.

Earth fresco by George Frederick Watts, 1854-5. Photograph courtesy of Malvern College, 2022.

Air and fire frescoes by George Frederick Watts, 1854-5. Photographs courtesy of Malvern College, 2022.

Air and fire frescoes by George Frederick Watts, 1854-5. Photographs courtesy of Malvern College, 2022.