In the modern era of digital journals, Louisiane Ferlier makes the case for engaging with their print predecessors, using the Royal Society Library's vast periodicals collection as an example.

This week I found myself musing on the fact that my name appears in a volume subtitled Science. Shock. Solution. Speed. Could this be that I contributed to advances in self-driving cars? Or did my niche expertise make it to the screenplay of the next 007 movie? Not quite.

The volume considers ‘Plan S’, an open access initiative for scientific publications, and my brief appearance consists of snippets from a tour I gave the author around the Royal Society’s shelves of scientific periodicals. So, allow me to give you a fuller view of this collection, as it’s truly a hidden treasure of our library.

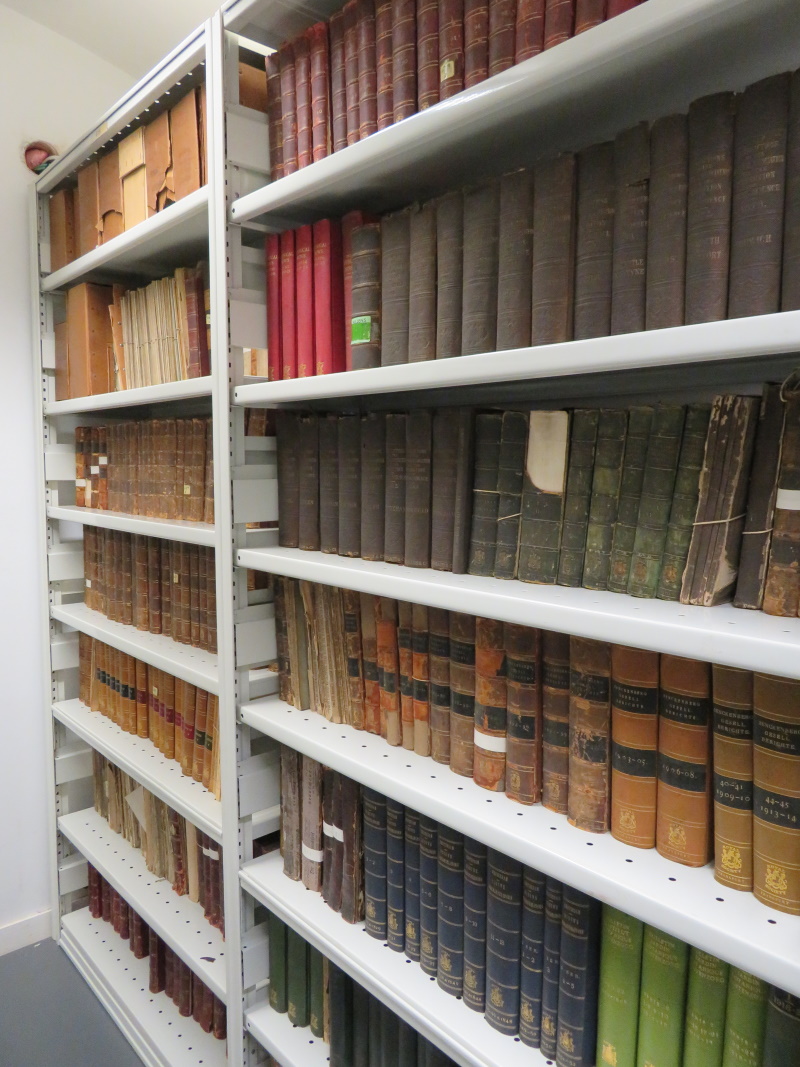

Scientific journals occupy a central and defining role in the diffusion of scientific ideas and therefore hold a place of honour within the Royal Society collections, running across several hundred metres of shelving in our stacks. But the advent of preprints, open-access and data sharing over the last 30 years has put some considerable distance between the physical periodicals stashed away in our basement and today’s scientific journal.

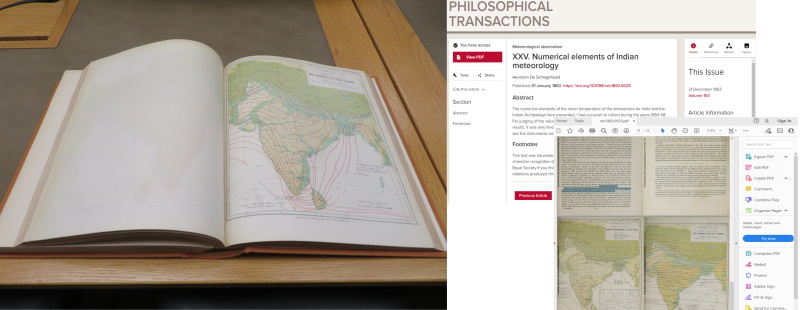

If scientific articles are by default digital-only today, a mere fraction of the historical scientific journals on our shelves have been digitised, and an even smaller portion is made available with the metadata that truly unlocks the knowledge within. Periodicals resist digitisation because, despite the fact that their very name hints at an ordered recurring organisation, they are in fact often published at irregular intervals, in varying forms and formats, and internally inconsistent.

In order to make digitisation impactful and meaningful, rich indexing is even more necessary than good images. The descriptive information for a book is often only a few lines long, but if you want people to find their way through a scientific journal, this metadata needs to be created for every single article, and machine extraction has so far proved only partially effective. The Royal Society successfully digitised its own historical journals in 2017, but we’re still continuing to improve on the platform, adjusting dates or adding missing items because of the complexity of the periodicals.

As scientists rarely use physical journals today and many historical titles have not been digitised by JSTOR, they are simultaneously at risk of disconnecting from the history of their discipline and of losing out on the serendipitous learning that comes from browsing in a library. Digital browsing is by nature directed, either by keywords or algorithms. The physical act of leafing through shelves and pages, however, opens the door to real chance encounters (especially if Aby Warburg is arranging the collection).

Although this is only possible in person, let me still give you a glimpse of how it feels to lose yourself in our collection of printed scientific journals. Here they are, metres and metres of periodicals waiting to be picked by readers:

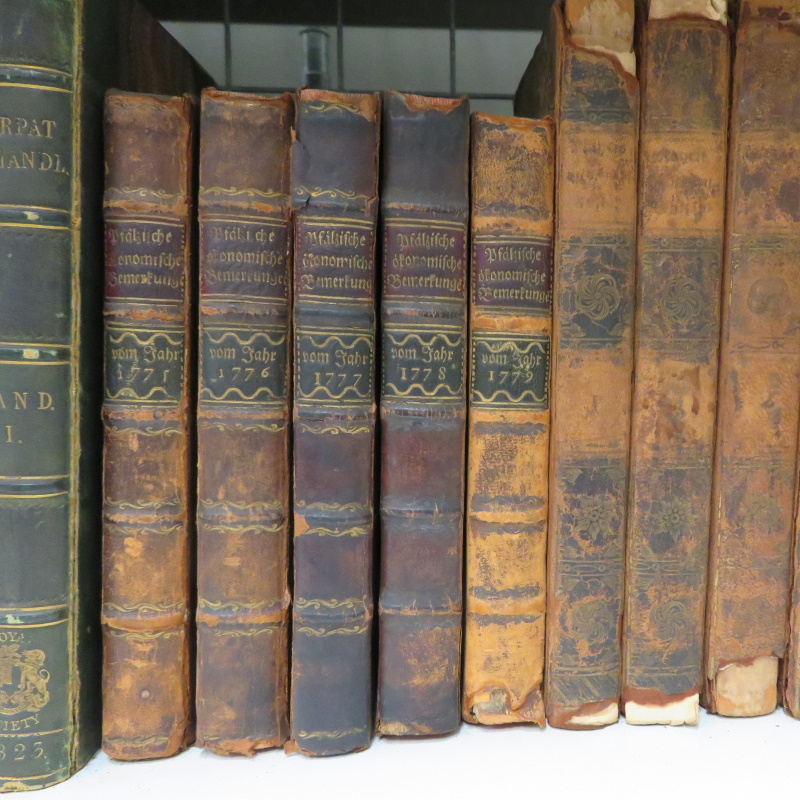

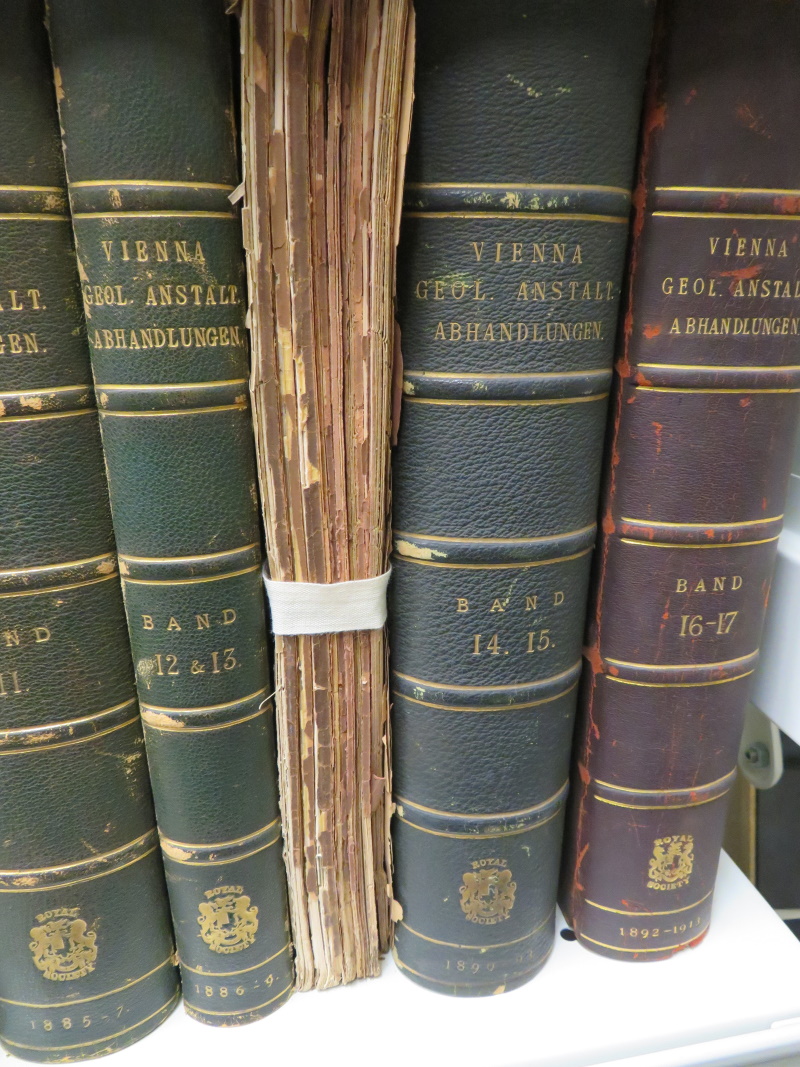

Walking along the shelves, you can witness the explosion of short-lived publications through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. You can observe from the titles on the spines the disciplinary specialisation of science, and you can see the gravitational power of western science and its political transformation over time. Here Revolutionary France publishes its own distinctive Republican journal away from the Académie Royale, and here colonial publications cease to exist to be replaced by titles announcing independent national scientific organisations. The very existence of this incredible collection reflects the fact that science is exchange and communication. Many of those titles were sent to the Royal Society by local, national and international academies, who donated their Journals, Memoirs, Acta, Proceedings, Transactions or Notes hoping for the Philosophical Transactions in exchange.

You can observe the comings and goings of scientific idioms, with Latin, French and German jousting with English to become the language of science. On my journey I happened upon a Latin translation of the Philosophical Transactions, various journals in French from the Imperial Russian Academy, and Japanese scientific periodicals published in English. I found it fascinating that all these Japanese publications by the National Research Council of Japan start in the 1920s and later realised that this corresponds to the TaishÅ period, when the country grew in international power, and presumably reflects the desire of Japanese scientists to have their work read and recognised abroad.

If the bulk of the collection is bound in matching volumes, some periodicals are still in loose stacks demonstrating how varied their formats are. The variety of topics is also mind-boggling as science has proven such an elastic category over time.

We certainly possess some rarities and oddities but what I like most about the collection is its potential to engage today’s scientists with the history of their discip-lines. Its rows of meteorological, magnetic and astronomical data are there waiting to join modern datasets and models. So, let this serve as an invitation to step away from the shock and speed of digital communication and leaf through the mountain of paper that came before Plan S.