An early Fellow of the Royal Society wrote about stone circles, the human soul, natural history and scurvy, as well as penning a gushing tribute to King Charles II. Rupert Baker provides an introduction.

At a very early meeting of the Royal Society, on 28 May 1661, it was ‘Order’d … that every one of this Society, that hath and shall publish any worke, doe give the Society one Coppy’.

Some of the early Fellows followed the order with alacrity: we have two full shelves of Robert Boyle’s books in our basement strongroom, for example. However, others appear to have missed that particular memo, leading your current librarians to hunt around in antiquarian and auction catalogues in an attempt to capture the key works of all Royal Society Fellows, particularly the earliest ones. A case in point is our purchase in the past few years of several books by Walter Charleton FRS (1620-1707).

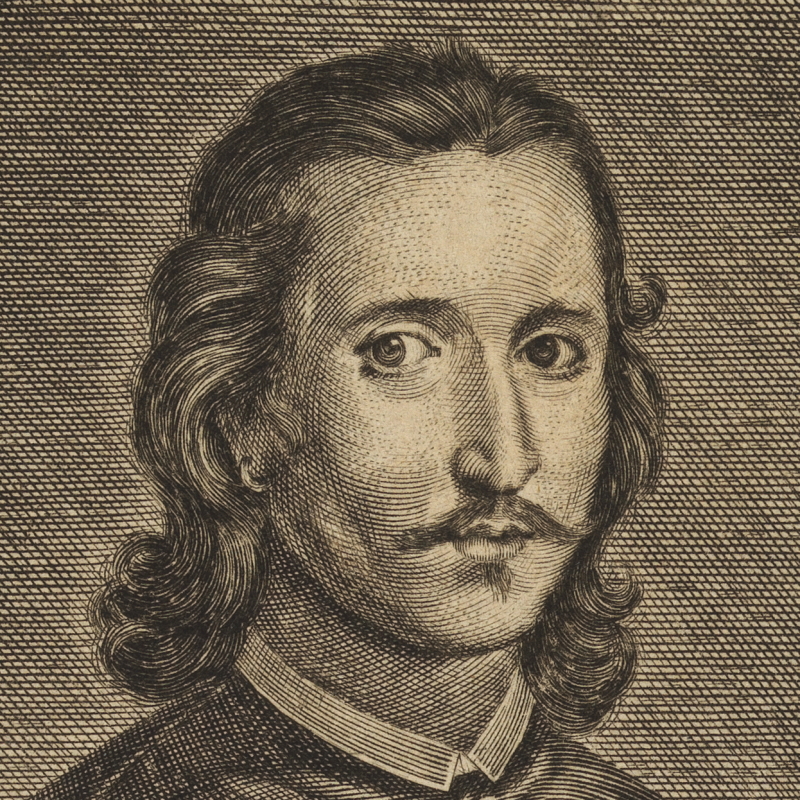

To be fair to Charleton, depicted in the rather suave portrait above, he was obviously a busy man with an eclectic set of interests. As an undergraduate in Oxford, he studied under future Royal Society Founder Fellow John Wilkins, and was then appointed at a very young age to the position of Physician in Ordinary to King Charles I.

This job, for obvious reasons, came to a sharp end in January 1649. Charleton moved to London, where he translated the works of his early influence, Jan Baptista van Helmont, and was admitted a Candidate of the College of Physicians in 1650. This same year saw the publication in Leiden of his first original work, Spiritus gorgonicus. We’ve just acquired a rather fine copy of this book from an antiquarian dealer, whose catalogue entry describes it as dealing ‘with a lithogenic spirit supposedly responsible for the formation of stones in the digestive and urinary tracts’.

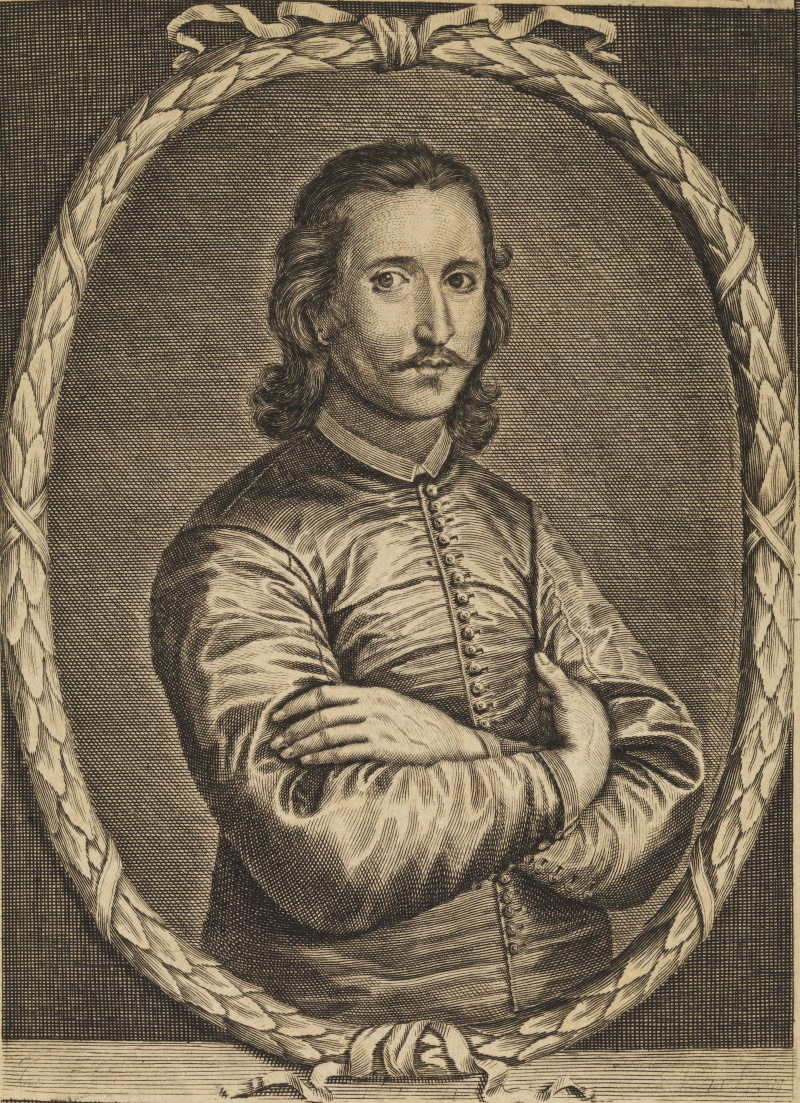

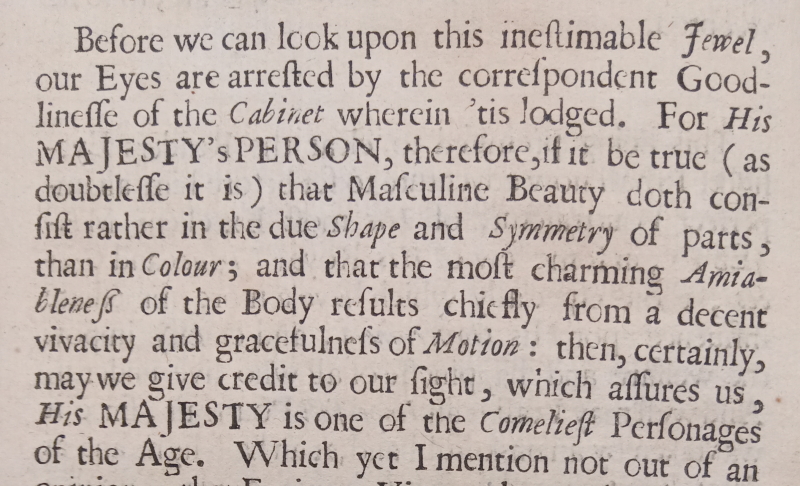

Further publications followed through the 1650s, on subjects as diverse as The darkness of atheism dispelled, Epicurus, and the Natural history of nutrition, life, and voluntary motion (all still on our wish list; donations always welcome!) Meanwhile, he maintained his royal connections as a travelling physician to the exiled Charles II, and kept his place at court after the Restoration. Just to be on the safe side, in 1661 Charleton published an extremely fawning pamphlet, An imperfect pourtraicture of His Sacred Majesty Charls the II. The imperfection lies with Charleton rather than His Maj, obviously:

‘And well may I call it an Imperfect Pourtrait, since it was taken by an unskilful hand … and therefore comes as much short of the inimitable Beauty of the Original, as a Sun painted doth of the true one.’

Smarmy! If you want more of this sort of thing, here's a snap from our copy, purchased from a book dealer in New Jersey a few years ago:

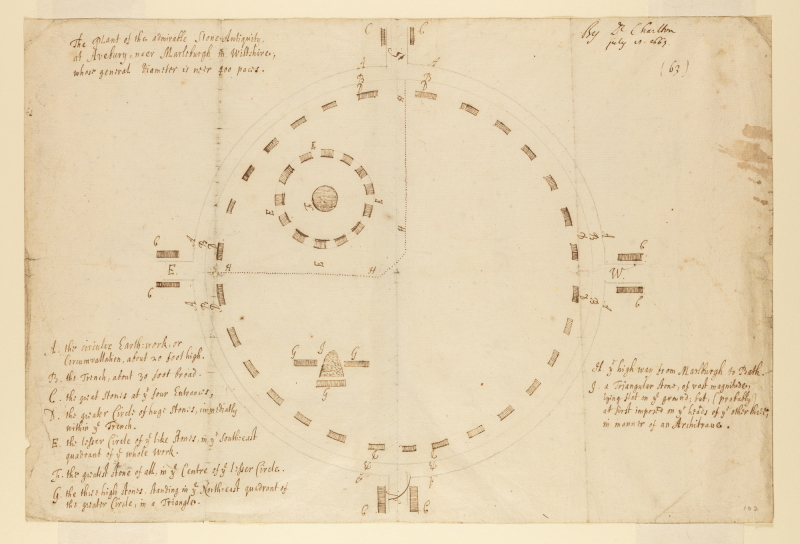

The year 1661 also saw Charleton swell the ranks of the early Royal Society, proposed on 23 January and admitted on 15 May. In December the following year, Charleton in turn nominated John Aubrey for admission to the Fellowship, and in 1663 – possibly under Aubrey’s antiquarian influence – Charleton’s research moved into rather unexpected circles. Stone circles, to be precise:

The above is Charleton’s plan of Avebury in Wiltshire, presented to the Royal Society at a meeting on 8 July 1663. The minutes record Charleton’s suggestion ‘that it was worth the while to dig there under a certain triangular stone, where he conceived would be found a monument of some Danish king’. His (erroneous) attribution of the monuments of Wiltshire to the Vikings also features in his book from the same year on Stonehenge, Chorea gigantum – another item on our Charleton wants list, though as you’ll see if you click on this auction link, we’ll have to save our pennies for that one…

If that’s not varied enough for you, we also have archival papers detailing Charleton’s dabblings in ‘the Sicknesses of Wines’, the whispering gallery in Gloucester Abbey and methods of preserving birds with powder, among many other topics. The bird theme reoccurs in printed form in his work on nomenclature in the animal kingdom, Onomasticon zoicon (1668). We’ve owned this one for a while, and have digitised a selection of the splendid birds (plus a very odd fish) in this gallery on our Picture Library. Interestingly, another recent purchase, Exercitationes de differentiis & nominibus animalium (1677), repeats some of the birds in reverse – note the splendid hoopoe facing left rather than right, for example – suggesting creative re-use and re-tracing from the original copper plates:

I snapped these with my phone when we took delivery of the book in January, and despite the drop-off in quality compared to the Picture Library, I can’t resist adding one more – this ‘Siyah-ghush’. A lynx, presumably?

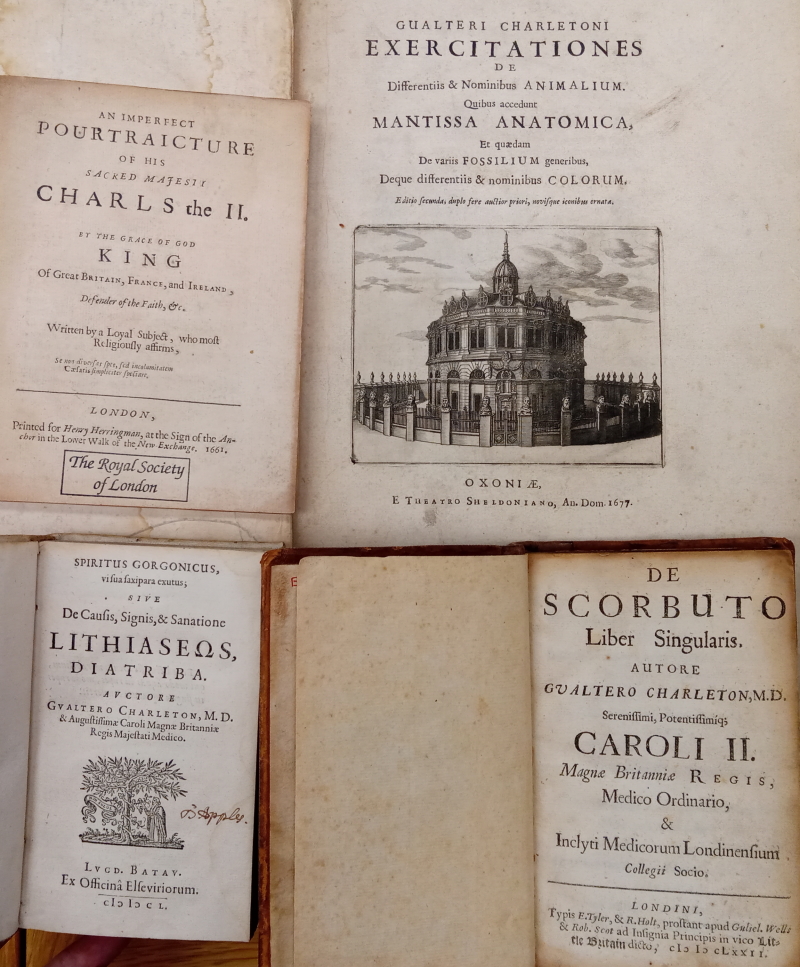

Our final ‘recent’ Charleton acquisition does return to his medical roots: De scorbuto liber singularis (1672), a book on the treatment of scurvy which we purchased from a Boston dealer in 2014. Here’s the title page, bottom right, along with the Charles II pamphlet, the Exercitationes and Spiritus gorgonicus:

By the time his book on scurvy was published, Charleton’s period of activity at the Royal Society had ended. His later years were divided between his London medical practice, his writing career and his various roles at the (now Royal) College of Physicians, up to and including the presidential chair from 1689-1691. According to his RCP biography, he even took up the post of Harveian Librarian at the age of 86 – the pinnacle of every man’s career, as my librarianly readers will surely agree.

As noted at the start of this post, his diligence in donating books to our Library is one of the less laudable aspects in the eclectic life of Dr Charleton. It gives us modern-day custodians something to chase after, however – so if you do have a spare copy of Chorea gigantum, The immortality of the human soul (1657) or The harmony of natural and positive divine laws (1682), then you know who to call.