The appointment of Isaac Newton and Edmond Halley to senior posts at the Royal Mint didn't mean that business always ran smoothly, as Virginia Mills discovers via letters in the archives of the Royal Society.

In 1696 Isaac Newton was appointed to the Royal Mint at the Tower of London and took in hand the ‘Great Recoinage’. His task was to gather all silver coins, the currency of the realm, which had become dangerously devalued by ‘clippers’ removing the edges and by a profusion of counterfeits in circulation. The silver would then be melted down and reissued in new coins of proper weight and value.

Newton brought a single-minded diligence and efficiency to the task of standardising the coinage – you can read more in Oxford University’s research project Newton and the Mint. Shortly after taking up his post, he recommended Edmond Halley for the post of Deputy Comptroller of the provincial Mint in Chester. Provincial Mints had been set up in the strategic trading cities of Bristol, Exeter, Norwich and York, as well as Chester, to support the recoinage deemed essential to maintaining Britain’s ability to trade internationally. However, the Mints were managed by local dignitaries and day workers and were notoriously corrupt, operating on systems of favouritism and bribery and trying to administer an unpopular programme. People were reluctant to give up their silver without knowing when it would be reissued to them as reminted coins.

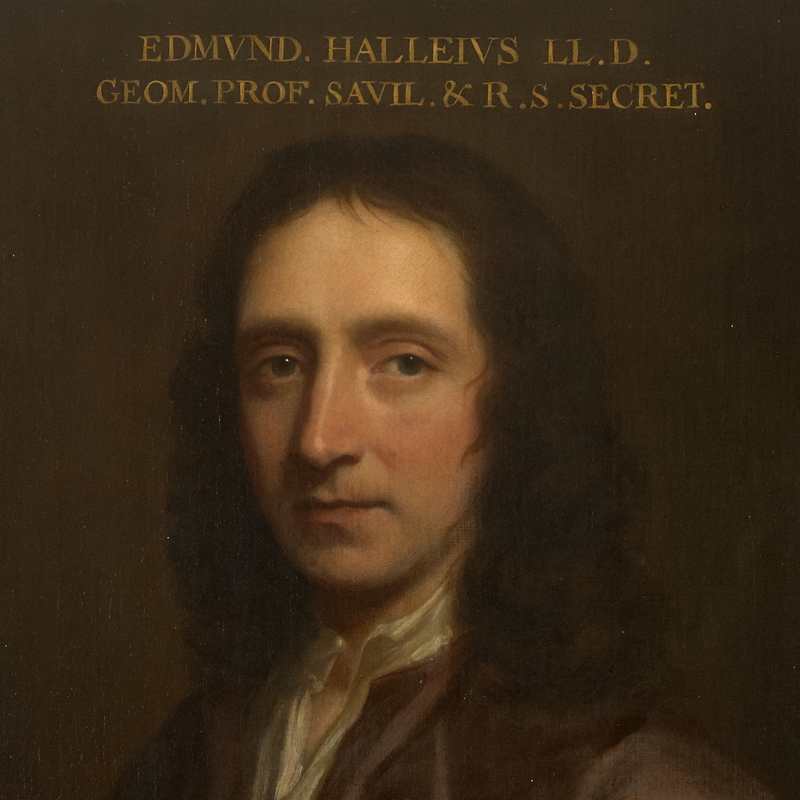

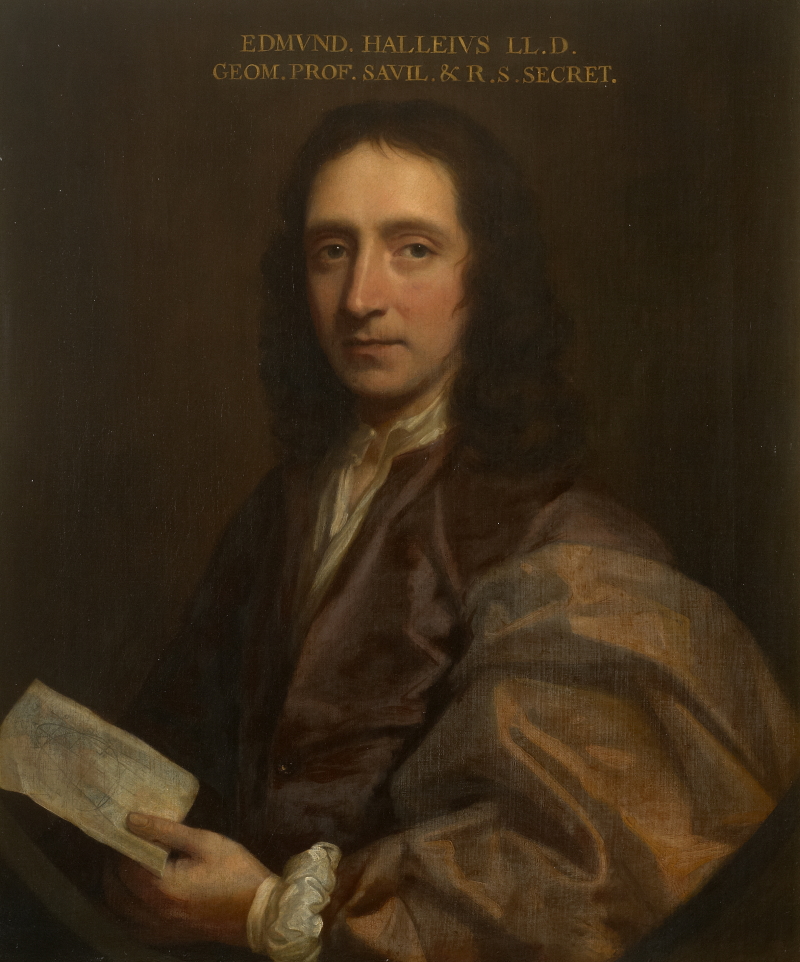

Portrait of Edmond Halley by Thomas Murray c.1690 (RS.9284)

Portrait of Edmond Halley by Thomas Murray c.1690 (RS.9284)

Halley and Newton were friends and fellow Fellows of the Royal Society, and Halley had been editor of Newton’s masterwork Principia Mathematica. However, if Newton hoped that Halley’s appointment would help him exert some bureaucratic control over the Chester Mint, he must have been disappointed by the subsequent workplace disputes and accusations of fraud – accusations which included a challenge to a duel between Mint staff!

Thanks to letters surviving in the Royal Society’s archives between Halley, Newton and Thomas Molyneux, we can see Halley’s account of these events in his own words. It seems that Halley and the Deputy Warden, a Mr Weddall, tried to root out the corrupt practices in order ‘to see the King’s business well and faithfully performed’ by ‘providing moneys for the nation’. They ran up against an ‘adversary’ in Mr Clarke, Master of the Chester Mint, who Halley implied was benefitting from bribes to issue reminted coins to people out of turn – in other words, not in the order in which they had handed over their silver.

In a letter of February 1697 Halley reported to Newton that Clarke was absent in London for two months, and those remaining in Chester were doing all his work. Halley nevertheless continued ‘serving the publick by giving a constant attendance and animating all parts of the mint’, successfully issuing 5000 new coins in five weeks (MM/5/41). Though Halley clearly resented the shirking Clarke’s absence, it may have been a happier workplace without him.

By August 1697, Clarke was on the road to London again with two junior cronies from the Chester Mint, with (as Halley wrote to Newton) ‘a resolution to loade on the Warden and my self, with all the calumnys he can’. Halley defended himself, saying ‘I am conscious to myself of no transgression, so I doubt not but to acquit my self of any imputation their malice can invent’. He asked Newton to intercede on his behalf, or at least allow him to answer Clarke’s accusations before passing judgement (MM/5/42).

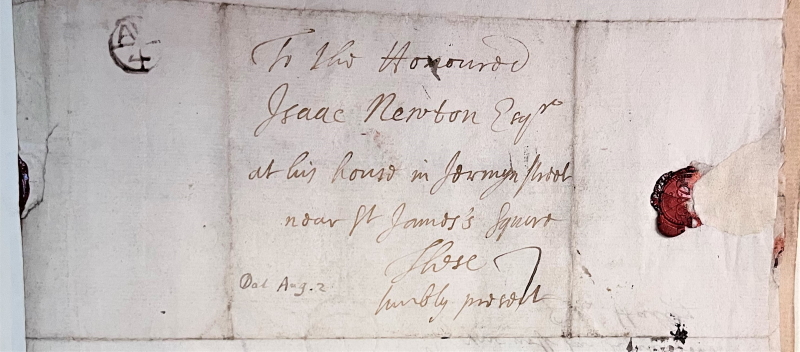

Halley's letter to Newton, August 1697

Halley's letter to Newton, August 1697

In December the same year, a further letter from Halley declared that in response to the charges levelled against him by Clarke and his supporters he would not resign, but felt the need to respond by bringing counter-prosecutions against them for their demonstrable transgressions. Edward Lewis, one of Clarke’s gang, was accused of ‘throwing a standish’ (a pen stand) at Weddall, giving ‘undue preferences’, and other misdemeanours. Halley desired Newton to sanction Clarke, advising him to ‘charge that proud insolent fellow whom I humbly beg you to believe the principal author of all the disturbances we have had at our mint, whom if you please to see removed, all will be easie.’ (MM/5/43)

The petty throwing of inkstands at colleagues and more serious accusations of favourable treatment – presumably corruption for favours or bribes – were not the worst of it. A letter from Halley to Molyneux noted that, back in October and November 1696, Clarke had borrowed a sword and threatened to waylay Deputy Warden Weddall on his way home, after the latter’s ruling against some clerks in the latest dispute over incorrectly weighed coin. Having failed in that, the next time the tellers were accused of theft when underweight shipments of coin went out, Clarke ‘pretended to challenge the Warden, came before the hour with his man and horses contrary to agreement … and staid not after it, by which means they did not fight.’ (MM/5/46).

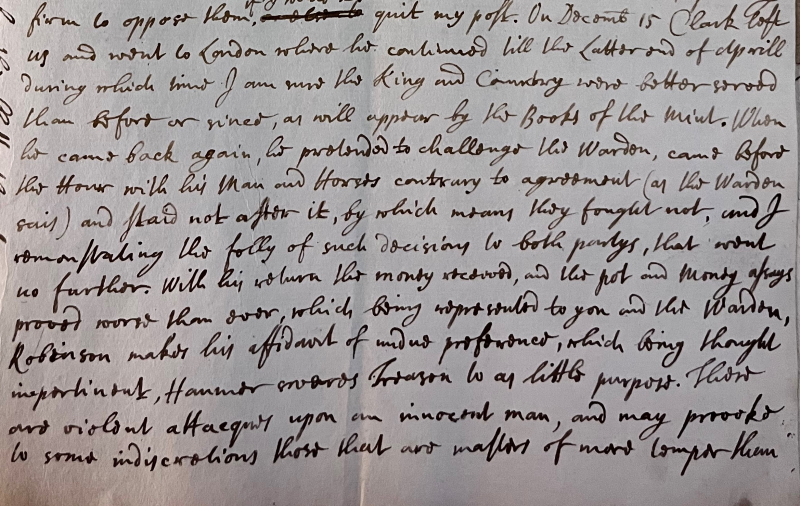

Halley's August 1697 letter to Molyneux, recounting the pretence by Clarke of challenging Weddall to a duel

Halley's August 1697 letter to Molyneux, recounting the pretence by Clarke of challenging Weddall to a duel

Halley of course was pleading his own case, so we are getting a one-sided view, but he certainly painted a vivid picture of Clarke as corrupt and blustering, inefficient in his job and deflecting attention from his misdeeds by levelling belated accusations at others. The provincial Mints were discontinued in 1698, which sounds like it might have been for the best, if only to avoid wholesale workplace warfare in the Chester branch!

During his short stint in Chester, Halley continued to correspond with the Royal Society on local matters he thought might be of interest to his fellow philosophers back in London. He sent accounts to Hans Sloane of diverse Chester phenomena: the local geology, a recently unearthed Roman altar, and a male greyhound that appeared to have given birth to a puppy ‘per anuss’ (EL/H3/49). Only two of those three were published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society; I’ll leave you to speculate as to which was passed over.