Professor Anita Guerrini looks at how some eighteenth-century parents decided to subject their children to the risk of smallpox inoculation in the belief that they were acting in their best interests, whether for reasons of dynasty or affection or both.

Although smallpox could attack at any stage of life, the majority of its victims were children. It is therefore not surprising that most of the inoculations reported to the Royal Society’s secretary James Jurin between 1721 and 1727 were performed on children.

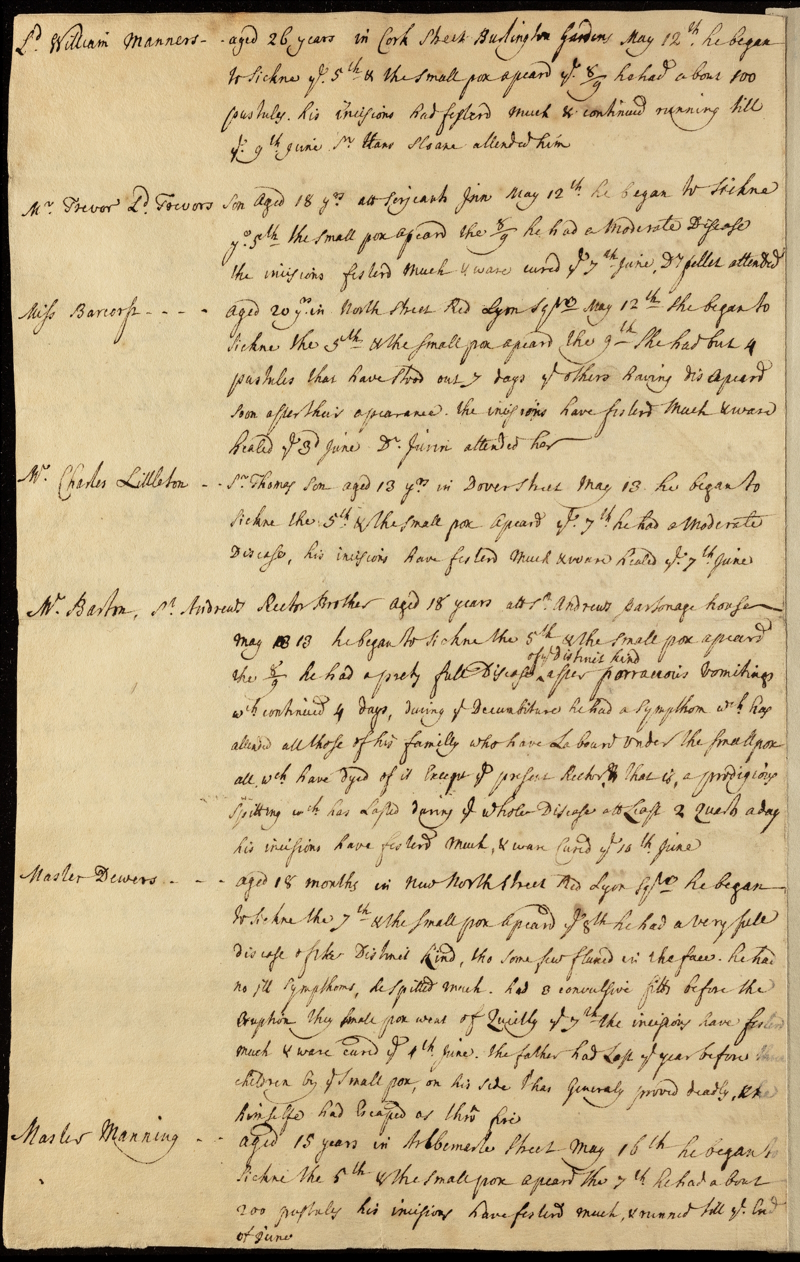

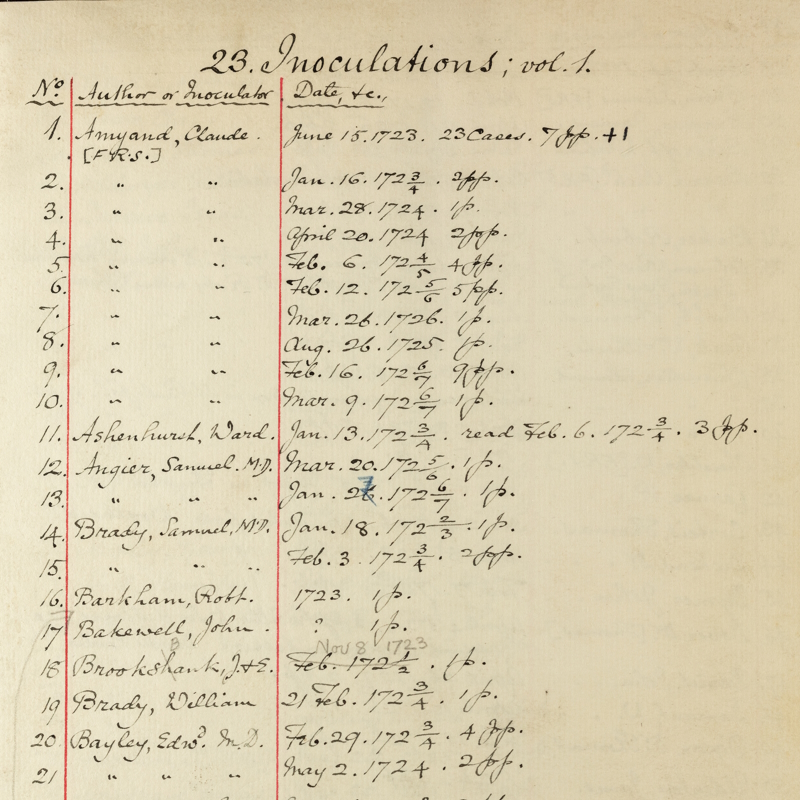

Jurin solicited these reports in order to demonstrate statistically the efficacy of inoculation; he was confident that smallpox induced by deliberate inoculation was less deadly than natural smallpox. However, the reports he received, now in the Royal Society’s archives, included far more than numbers. Written by a wide range of practitioners – physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries – across Britain, these reports tell stories of anxious parents who wanted to remove at least one of the many barriers that stood before their children in their struggle to reach adulthood. While some of the reports simply listed names and numbers, many more gave considerable detail.

Inoculation was hardly a panacea. It infected someone with what was hoped to be a non-lethal case of smallpox, and apart from the risk of the disease there was the danger of infection from the procedure, which involved ripping open the skin (usually of an arm) with a needle of doubtful cleanliness and inserting some ‘matter’ of smallpox into the wound. Inoculation differed from vaccination, which was introduced at the end of the eighteenth century, and which employed a different, much less dangerous microbe – cowpox – to induce immunity. Inoculation with smallpox itself soon disappeared after 1800.

The progress of the inoculated disease could be long and agonizing, lasting for several weeks. Sometimes the patient contracted a mild case of smallpox and survived, in theory immune to further outbreaks. Other times the patient became seriously ill or died, and varied results could happen in the same community, even among family members who would have been inoculated from the same source. Three of the four Brooksbank siblings survived inoculation in 1723, but the youngest did not. From Halifax, William and Phebe Clark reported the inoculation of two of their children, ‘ye One a Boy aged about 5 Years & a half, ye Other a Girl about 3 Years old.’ While the girl had a mild case, with few spots, the boy became seriously ill but ultimately survived.

The practice of inoculation remained experimental because no one knew how or why it worked, or didn’t work, and the human trials that took place in 1721 did not employ controls or other means to prove efficacy and safety. The first inoculation in England took place in 1721, when Lady Mary Wortley Montagu persuaded the surgeon Charles Maitland to inoculate her three-year-old daughter. Maitland had been surgeon to the British embassy in Constantinople and was one of the few in England who was familiar with the Turkish practice of inoculation.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, between 1715 and 1720 (Yale Center for British Art - public domain)

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, between 1715 and 1720 (Yale Center for British Art - public domain)

Urged on by Sir Hans Sloane and other elite physicians, Maitland performed public trials later that year, first on six prisoners at Newgate, and then on a group of orphans in St James’s Parish. The latter trial had been proposed by Caroline, Princess of Wales, who sponsored at least one other public trial before Royal Surgeon Claude Amyand inoculated two of her daughters in the spring of 1722. Maitland and Amyand performed a great number of inoculations over the next few years, and their records are in the Royal Society Archives. It’s quite possible that they expunged any unsuccessful cases, but the successful cases could be harrowing enough, with multiple complications and long recoveries.

Medical men were among the first in line to obtain inoculations for their children, even though they were not always enthusiastic about performing the procedure themselves. Amyand inoculated the Royal physician Sir Hans Sloane’s grandson; although Sloane had supervised the Newgate trials he trusted Maitland to perform the inoculations. Maitland inoculated the son of his friend Dr James Keith, who had already lost another son to the disease. Keith had witnessed Maitland’s inoculation of Lady Mary’s daughter.

Lady Mary, a vocal advocate for inoculation, recognized the importance of Princess Caroline’s support in persuading her fellow aristocrats, but they also had other reasons to embrace the practice. European history held ample evidence of the disruptive effects of disease on inheritance and succession; had Queen Anne’s son, the Duke of Gloucester, not died of (perhaps) smallpox in 1700 at the age of 11, Caroline would have been only a minor German noble. She had fallen ill with smallpox shortly after the birth of her son Frederick in 1707, and she sent Maitland to Germany to inoculate Frederick in 1722, supposedly paying him £1000.

Historians maintain that during the eighteenth century, childhood began to be viewed as a distinct phase of life. Children were no longer merely miniature adults, and paediatric medicine began to emerge as a discipline. Yet did aristocratic children remain chattels in a game of marriage-chess?

In any case, to make a child ill deliberately with a potentially deadly disease was not an easy decision. One aristocratic parent, Catharina Lady Percival, kept a journal in 1725 that detailed the inoculation of her three-year-old son George. Her close observation of her little boy over the lengthy course of his inoculation-induced smallpox shows not only her fine observation skills and her mastery of current medical thinking but also her affection for her son and her anxiety over the outcome of the procedure.

Catharina was delighted when George was ‘mighty impatient for chicken or pig’, or when he could ‘whip a Top or beat a Drum’, but she kept close count of his ‘pocks’ and each day that his fever did not abate made her ‘uneasy’, even with the assurances of Amyand that all was going according to plan. When, after about three weeks, George appeared to be completely healed (including the obligatory post-fever purgings), she wrote, ‘I thank God he is as well as ever he was in his life’. Her joy would be cut short, however, by George’s death from unknown causes the following year.

Jurin determined from the reports of Amyand, Maitland and many others that one in fifty died of inoculated smallpox, compared to one in eight for the natural variety. No one wanted to be that fiftieth parent, yet many believed that the risk was worthwhile. In deciding to subject their children to such risks, eighteenth-century parents believed that they were acting in the best interests of their children, whether for reasons of dynasty or affection or both.

You can also read Professor Guerrini’s ‘In focus’ article, ‘Smallpox in the archives’, on our Science in the Making platform.