Jon Bushell tells the stories of some of the longer and shorter Presidential terms at the Royal Society - and one famous scientist who refused the job altogether.

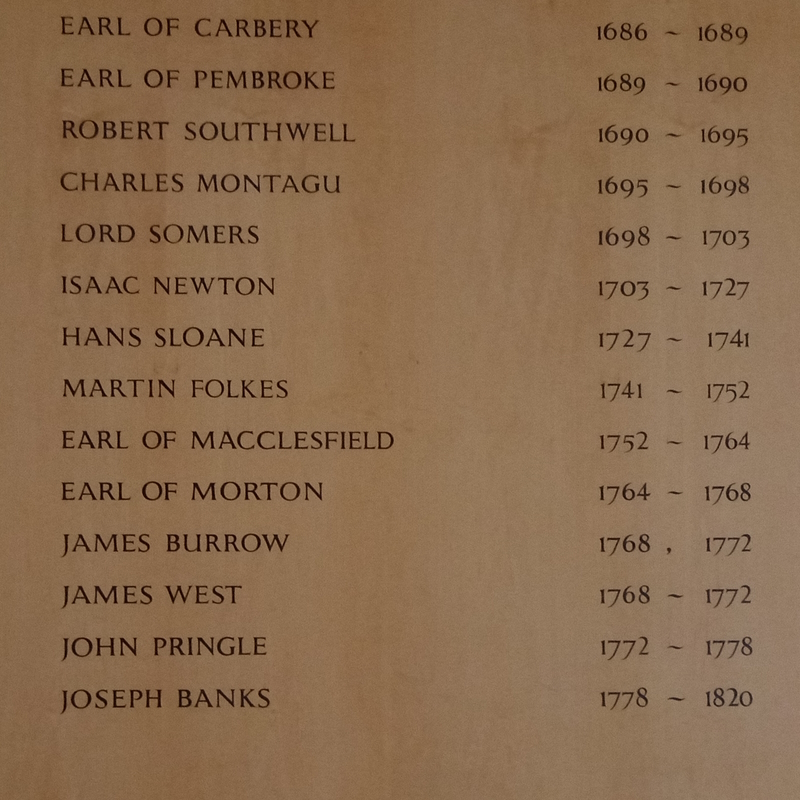

When I find myself leading visitors on tours of the Royal Society at Carlton House Terrace, I usually make a point of stopping by the Presidents’ Board. It lists the names of every Fellow elected to lead the Society since the Royal Charter of 1662, in which Viscount Brouncker was appointed as the Society’s first President.

The role has evolved over the years, but many of the responsibilities outlined in the early charters are still relevant. The President chairs the Society’s Council, overseeing its administrative and financial management and the appointment of Committees.

Many famous Fellows have held the title over the years, including the likes of Christopher Wren, Isaac Newton and Humphry Davy. Lengths of service have varied considerably, however. Joseph Banks holds the record for longest-serving President, taking up the role in 1778 and continuing right up until his death in 1820. Newton held the position for over two decades, being appointed in 1703 and dying while still in post in 1727.

Portrait of Isaac Newton painted by Charles Jervas in 1717, during Newton’s Presidency. RS.9252

Portrait of Isaac Newton painted by Charles Jervas in 1717, during Newton’s Presidency. RS.9252

That said, you could make the argument that the Society was never truly Royal under Newton’s tenure. Queen Anne came to the throne in 1701, but the President at the time, John Somers, never asked her to take up the role of Royal Patron. This state of affairs continued when Newton took office two years later. Similarly, when George I succeeded Anne in 1714, it seems that no attempt was made to appoint him as Royal Patron. Newton’s successor, Hans Sloane, finally made the necessary arrangements in May 1727, just a month before George I died. If Newton had hung on a little longer, we might have missed him as well.

Looking at the whole of the Society’s history, however, lengthy Presidential terms such those of Newton and Banks are clearly in the minority. The average term is around six years, in large part due to the implementation of the five-year limit in the nineteenth century. Even before this, many Presidents chose to resign after a few years to pass the duty along to a successor, to be elected at the Society’s anniversary meeting in November.

The President’s chair, complete with Royal Society coat of arms, was used for official meetings throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The President’s chair, complete with Royal Society coat of arms, was used for official meetings throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

It wasn’t always easy to line up a suitable Presidential candidate. One particularly famous example from 1857 involves then-President Lord Wrottesley. He was intending to offer his resignation, and Council were keen to appoint Michael Faraday as his successor. A deputation from the Society, consisting of Wrottesley, John Peter Gassiot and Sir William Grove, approached Faraday at his home to formally offer him the position, but he refused to accept it. In the end, Wrottesley had to remain President until the anniversary meeting in 1858, when Sir Benjamin Brodie succeeded him.

There are a few reasons why Faraday may have turned down the offer. When discussing the matter with John Tyndall the following day, Faraday felt that his declining mental faculties would render him incapable of effectively carrying out Presidential duties. He might also have been worried about the costs involved. Typically, Presidents tended to be men of wealth, as the role was unpaid and came with additional financial burdens. That included the Presidential Conversazioni, exhibitions which certainly weren’t cheap. The main costs would eventually be taken over by the Royal Society from 1872.

Edward Armitage’s 1873 painting, ‘Deputation to Faraday’. RS.9675

Edward Armitage’s 1873 painting, ‘Deputation to Faraday’. RS.9675

If the Presidential chair became vacant before the anniversary, it fell to Council to appoint a successor until a formal election could take place. In many cases, the ‘interim’ candidate would be selected anyway, though this wasn’t always the case. James Burrow, for instance, is not only one of the shortest-serving Presidents in the Society’s history, but also the only man to hold the office twice.

In October 1768 the Earl of Morton died while President, and so Burrow was appointed to the office for one month until the anniversary meeting election of James West. When West died in July 1772, Burrow again took office until John Pringle’s Presidency. If we consider both of Burrow’s terms together, he held the Presidency for a total of 187 days, which makes him the second-shortest serving President of the Society. The chemist William Hyde Wollaston holds the record for the least amount of time spent in office, at just 155 days. What makes this more interesting is that unlike Burrow, Wollaston was interested in serving as President for a full term.

Portrait of Joseph Banks as President of the Society, sitting in the Presidential chair. Painted by Thomas Phillips in 1809. RS.9544

Portrait of Joseph Banks as President of the Society, sitting in the Presidential chair. Painted by Thomas Phillips in 1809. RS.9544

His brief appointment in 1820 reflects the unique circumstances the Society found itself in at the time. Banks’s mammoth Presidency was coming to an end after more than 41 years. In failing health, Banks attempted to offer his resignation in May, which Council members unanimously refused. By June 1820 Banks was dead and Wollaston was appointed until the November election. Wollaston had the backing of several younger Fellows, including Charles Babbage, who saw him as a reform candidate who could bring a renewed emphasis on mathematics and physical sciences. Nevertheless, it was the ambitious Humphry Davy who went on to be elected at the anniversary meeting; Dr Andrew Lacey covered this affair in more detail in a guest blogpost last year.

These days, a President’s scientific accomplishments are considered rather more significant than their personal ambitions or the size of their bank accounts, with eighteen of our Presidents having won Nobel Prizes for their scientific accomplishments since the awards were founded in 1901.