From Chelsea College to an agricultural estate in Mablethorpe, Jon Bushell looks at the various properties owned by the Royal Society over the centuries.

The Royal Society received its first Royal Charter from King Charles II in 1662. The Charter outlined how the Society would be governed and established various privileges. Interestingly, these included a right ‘to have, acquire, receive and possess lands, tenements, meadows, feedings, pastures, liberties, privileges, franchises, jurisdictions and hereditaments’.

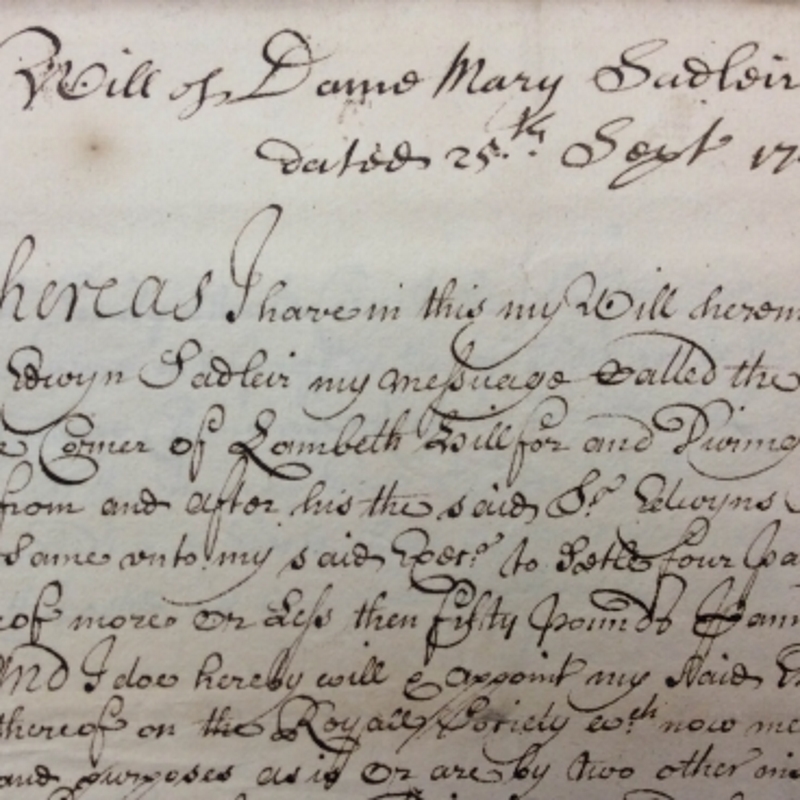

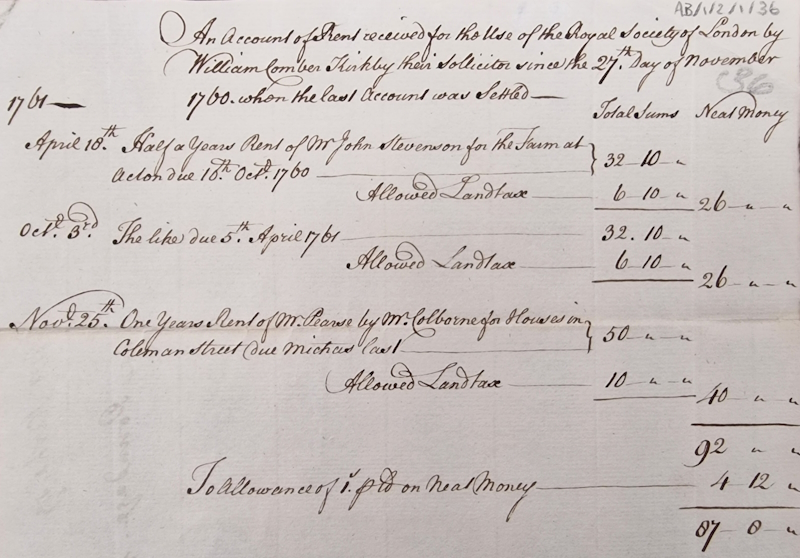

Extract from the accounts detailing rental incomes received by the Society in 1760 and 1761 from property in Acton and Coleman Street (AB/1/2/1/36)

Extract from the accounts detailing rental incomes received by the Society in 1760 and 1761 from property in Acton and Coleman Street (AB/1/2/1/36)

Property management might not seem like obvious business for the Society to be engaged in, but in fact it has exercised this right on numerous occasions. In its early years, the Society hoped to build a college of its own – its tenure in Gresham College was by no means secure, as was evidenced when the Fellows were turfed out for a few years in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London.

The Duke of Norfolk agreed to host the Society’s weekly meetings at Arundel House, near the Strand on the banks of the River Thames. In the following year, 1667, he made a generous offer of a plot of land in the grounds of the house. The Society would be allowed to build a college there, as long as it could raise the funds. The Council made a considerable effort to solicit donations from the Fellowship, though not everyone was keen: Samuel Pepys, for example, complained in his diary that he ‘was forced to subscribe to the building’. In the end, the fundraising fell short, and the project was quietly abandoned in 1669.

One reason the Council may have given up on Norfolk’s offer was the issuing of the Society’s third Royal Charter in 1669. This included a grant from the Crown of the lands of Chelsea College, established early in the seventeenth century but fallen into disuse by the time the Society took possession. The intention must have been to restore the buildings and occupy them, but very little effort seems to have been spent on this. In the end the Society sold the lands back to the King in 1682 for a tidy sum of £1,300, and eventually this became the site of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

Plan of Chelsea College lands granted to the Society in the third Charter (RS.15102)

Plan of Chelsea College lands granted to the Society in the third Charter (RS.15102)

There were no further efforts by the Society to build a college, and meetings eventually returned to Gresham. However, the Gresham trustees asked the Society to leave in 1710, and Council – headed by Sir Isaac Newton PRS – settled on buying two properties in Crane Court for £1,450. One of these became the Society’s home for most of the eighteenth century, while the second was rented out to provide an annual income of £24. Interestingly, Crane Court is the only home the Society has purchased outright. The properties were sold in 1780 when the move to Somerset House took place, into rooms owned by the Government. The next home, Burlington House, was also Government property, and our current location in Carlton House Terrace belongs to The Crown Estate.

House in Crane Court, purchased by the Royal Society in 1710 (RS.13304)

House in Crane Court, purchased by the Royal Society in 1710 (RS.13304)

The right to own land and property was an important source of income for the Society, and the earliest land investment to provide rental income was purchased as early as 1674. A sum of £400, left to the Society in the will of John Wilkins, was invested into fee farm rents in Lewes. Despite several disputes over land taxes and late payments, the rents brought in a steady income for the Society until well into the twentieth century, only being sold in 1939. Francis Aston bequeathed a similar agricultural estate in Mablethorpe to the Society in 1715, which also provided a useful income.

Annotated photograph of the Mablethorpe estate, 1925 (Deeds and Charters collection)

Annotated photograph of the Mablethorpe estate, 1925 (Deeds and Charters collection)

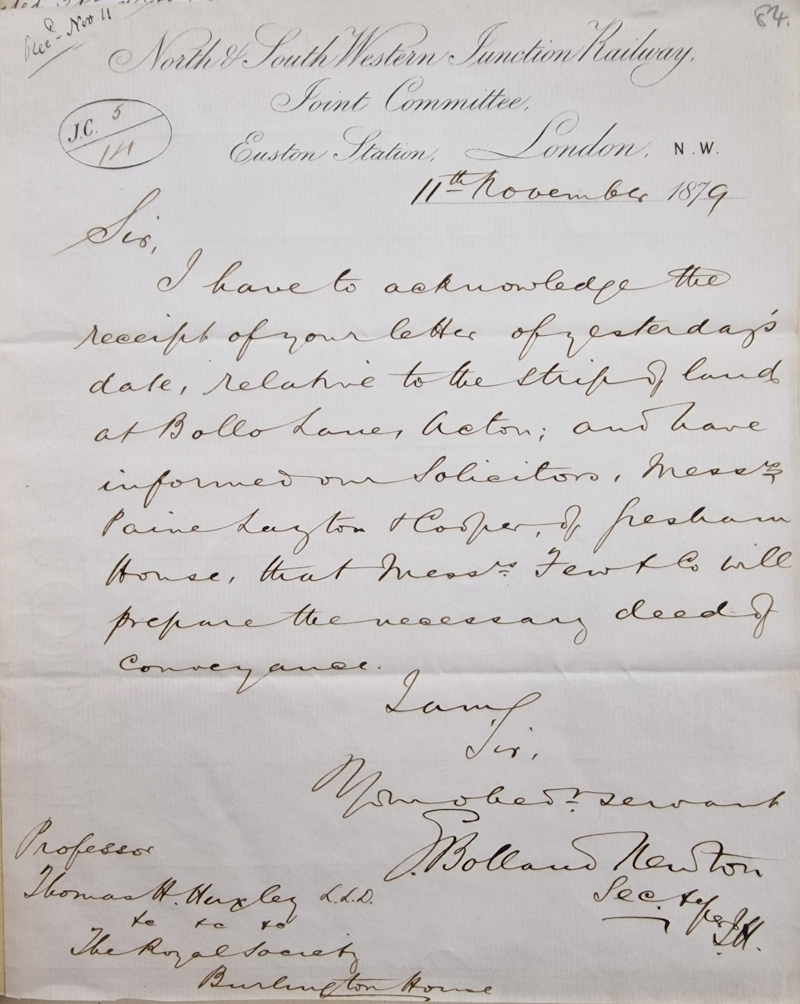

Regular rents provided vital financial support for the Society’s journal publishing and other activities, especially given how lax some Fellows could be about paying their subs on time. A crackdown on arrears under the Presidency of Sir Hans Sloane raised enough to buy a 48-acre estate in Acton for £1,600 in 1732. As London expanded, the value of the estate rose considerably. Parcels were sold off at various times, and some of the land was subject to a compulsory purchase order in the 1870s as the new Ealing Acton and City Railway expanded to the west of the capital. Nevertheless, when the remaining 30 acres were sold in 1882, they went for twenty times the original price.

Letter from George Bolland Newton regarding the sale of land in Acton for railway development (DM/7/84)

Letter from George Bolland Newton regarding the sale of land in Acton for railway development (DM/7/84)

Several other London properties were owned by the Society at various times. Edward Paget left two houses in Coleman Street to the Society in his will in 1717, which brought in nearly £100 a year in rent until they were sold in 1835 for £3,150. It also bought several properties in 1883, including a row of houses in Kensington and the freehold of a property in Basinghall Street. This was damaged by bombing during the Second World War, but by the time the lease expired in 1972 the total ground rents received had exceeded £30,000.

Our most recent venture into the property market was in 2007, when the Society purchased Chicheley Hall in Buckinghamshire, running it as a conference centre until the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020. Today, other than the occasional situation where properties are bequeathed to the Society and sold on, we no longer own any other land or estates, having gradually wound down this activity as publishing, conferencing and other income streams have grown. I bet that land in Chelsea would be worth a bit if we’d held onto it, though.