Virginia Mills looks at the history of Fellowship elections to the Royal Society, including some recent procedural changes.

The Royal Society admitted its annual cohort of new Fellows and Foreign Members last week in the traditional admission ceremony. I hope those of you suffering from election fatigue will forgive me for turning your attention to the history of Fellowship polling at the Royal Society.

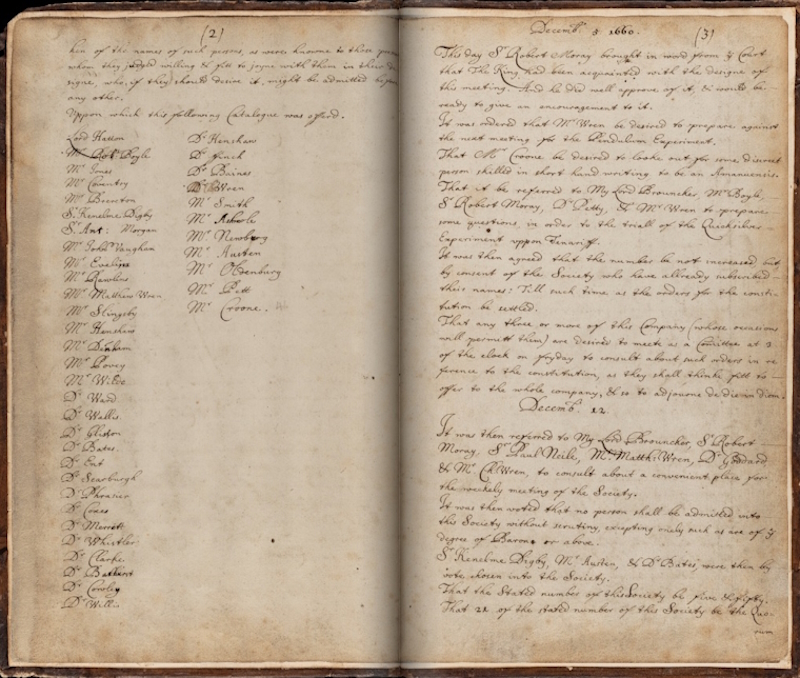

The first business for the Society’s twelve Founder Fellows was to select further individuals for invitation to join the fledgling college ‘for the promoting of Experimentall Philosophy’. The minutes of the first official meeting on 28 November 1660 concludes with a list of 41 names:

‘of such persons, as were knowne to those present whom they judged willing & fitt to joyne with them in their designe, who, if they should desire it, might be admitted before any other.’

The full list can be seen above, and in the digitised Journal Book volume 1. It includes such luminaries as Dr Thomas Willis, a pioneering physician who was already part of a circle of experimentalists in Oxford and who enhanced his medical reputation reviving Anne Greene, a woman hanged for infanticide; Elias Ashmole, alchemist and later founder of the Ashmolean Museum; John Evelyn, whose Sylva (1664) and Pomona, works on forestry and cider, are now read as early environmental treatises; and Dr William Croone, for whom the Croonian Medal and Lecture, still given at the Royal Society, is named. Croone was known for his work on muscle anatomy.

A formal election process was enshrined in the statutes of the Society when the second Royal Charter was granted in 1663. Whilst the process and procedures have evolved over the centuries, at its heart remains the principle that new candidates are selected by the existing Fellowship to join their ranks. I don’t have time to chart all the changes in our election statutes (you’ll be glad to hear) but I’ve pulled out some of the more interesting landmarks.

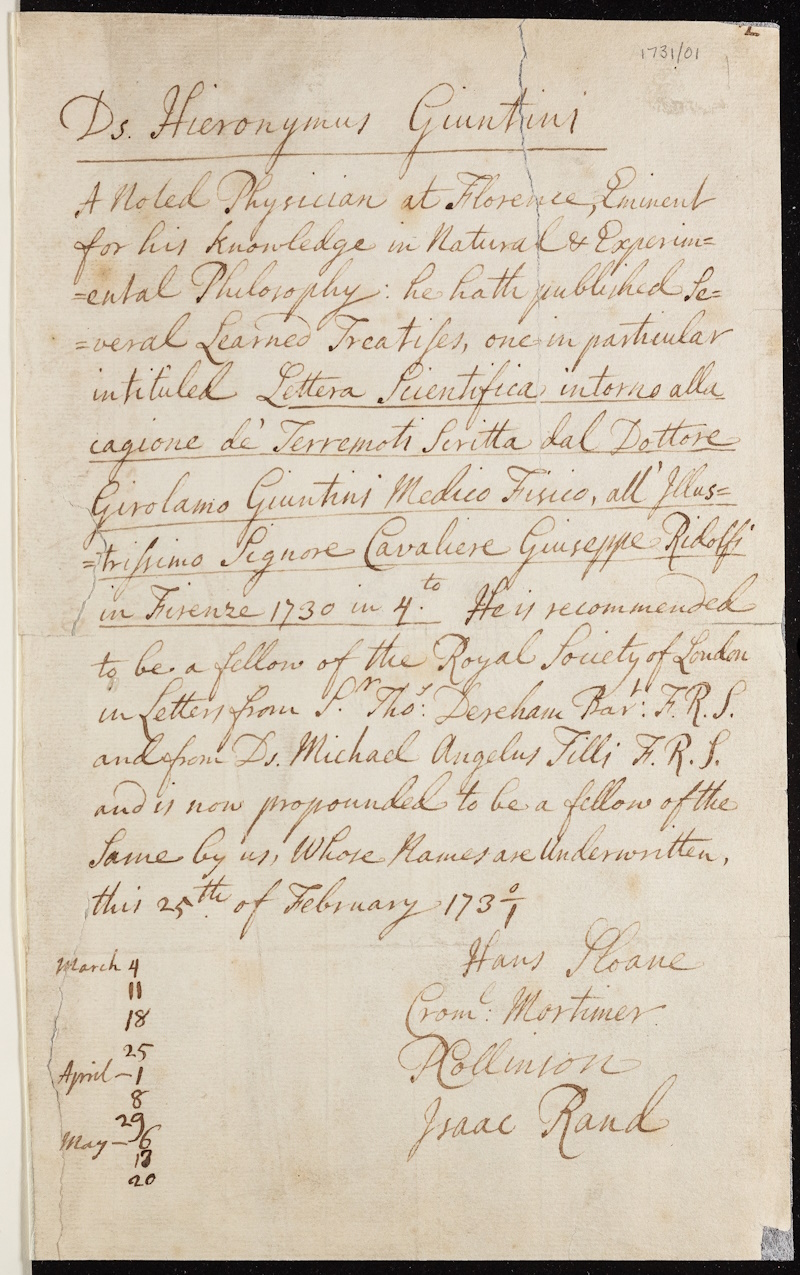

From 1730 monetary concerns led to more checks on elections. Many Fellows were defaulting on their subscription fees, so to guarantee their solvency (and to protect the quality and size of the Fellowship) the President, Sir Hans Sloane, took legal advice and brought into statute the requirement that all candidates be nominated by at least three existing Fellows. This led to the creation of formal election certificates in 1731, retained in the Society’s archives to form one of our longest unbroken series of records.

The first Royal Society election certificate, nominating Italian physician Dr Hieronymus Giuntini (EC/1731/01)

The first Royal Society election certificate, nominating Italian physician Dr Hieronymus Giuntini (EC/1731/01)

Election certificates are valuable as a roll of our membership and as a record of the major scientific achievements of the Fellowship, via the citations giving reasons for election. They also provide evidence of the networks at play in the web of science – who was nominating whom, and who wasn’t! To maintain confidentiality and the integrity of the election process, today’s certificates are only accessible 50 years after the date of election. Basic details, including a citation, can be found on our catalogue as soon as Fellows are elected, but images and details of proposers are only released after the closure period. Certificates of those not fortunate enough to be elected (lapsed certificates) remain confidential for even longer – 70 years.

Within the Fellowship, there was no anonymity in the nomination process. Certificates bearing the endorsement of three Fellows would be suspended in the Society’s meeting room for ten meetings, allowing the addition of signatures in support of the candidate. At the ‘eleventh’ meeting, Fellows present were balloted on whether candidates should be admitted. These days, scientists are assessed by committees of specialists, and a list of names is put forward for the consideration of the wider Fellowship. A candidate is elected if they secure two-thirds of the votes of those Fellows voting. You can see more on the current process on our ‘About elections’ page.

The ballot box shown above is thought to have been used at the Society in the early twentieth century. An anonymous system of black balls (for ‘no’ votes) and white balls (for ‘yes’) was also employed in earlier years.

Perhaps the most significant election overhaul came in the mid-nineteenth century following the death of Sir Joseph Banks, the Society’s longest serving President (from 1778-1820). Banks, best known for serving as gentleman naturalist on James Cook’s first voyage, was keen on admitting aristocrats into the Society – without the usual election procedures – if they could be useful patrons and supporters of science. There was, however, discontent amongst the Fellowship about the number of non-scientific Fellows potentially diminishing its intellectual standing.

Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks by Thomas Phillips, 1809

Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks by Thomas Phillips, 1809

In 1830 an additional control was brought in requiring more nominators – six supporters from the Fellowship were now required for a candidate. Then in 1834 when the Society was looking to trim numbers and professionalise, election certificates were made compulsory. Despite these changes, and an increase in membership fees, the Fellowship continued to grow, so in 1846 a Charter committee was appointed to advise on further restriction. They brought in the first limitation on the number of new Fellows recommended for election: 15 per annum, though the Fellowship could exceed this if they so desired. The Society at this point became much more exclusive, made up of only men (and, from 1945, women) of the highest scientific achievement and qualifications – as it remains to this day.

The Royal Society has, of course, continued to update its practices. In 2001 the number of proposers was reduced to two. This was intended to promote diversity in the Fellowship, as it was considered that the requirement for a larger number of signatures might discriminate against minorities in science such as women, those in new and emerging subjects, or those in institutions and organisations with few existing Fellows.

In 2023 reforms were introduced which affected the classification of Fellows, the committee structure supporting the election process, and the ways in which the Society supports the nomination process. These reforms were brought in with the aim of better representing scientists from non-traditional backgrounds, such as industry and commerce. In the review of elections in November 2023 it was agreed to increase the number of people elected to the Fellowship each year: from 2024, up to 85 new Fellows can be elected, and up to 24 Foreign Members. We’re privileged to welcome the 2024 cohort to join the ranks of almost 10,000 prestigious Fellows elected before them.