What do you show to a Library tour group interested in seabed mapping? Rupert Baker dives down to the vaults on a treasure hunt.

Royal Society Library staff host a large number of tour groups throughout the year, showing off highlights from the historical collections and taking visitors around our spectacular Grade I listed building.

We have a few items – Robert Boyle’s to-do list, for example – which we use as our ‘old favourites’, always guaranteed to raise the eyebrows of general interest groups. However, it’s nice to get a challenge (pun, as you’ll see later, intended) when specialists come to us with niche requests. These require a little background research before we pop down to the vaults with our trolleys, in search of less familiar material. Such was the case earlier this year when I hosted a delegation from the UK Centre for Seabed Mapping.

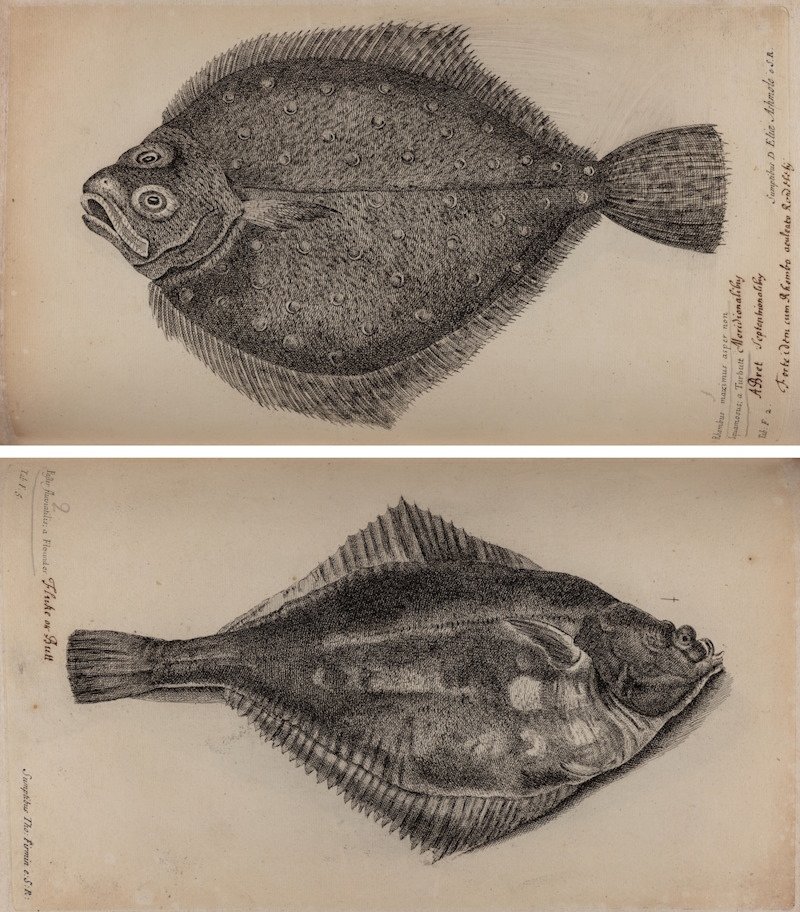

So, what do you show to seabed mappers? Well, assuming (correctly) that they’d be interested in things swimming around on the seabed, my first course consisted of some flatfish from Willughby and Ray’s Historia piscium – the famous ‘history of fishes’ that nearly sank the Royal Society’s finances in the 1680s:

Turbot (RS.21610) and winter flounder (RS.20613)

Turbot (RS.21610) and winter flounder (RS.20613)

If you’re going to descend to the seabed then you need to have perfected ‘the art of continuing long underwater’, the fourth item on Boyle’s list, so our group was fascinated to hear about an early step in this direction: Edmond Halley’s diving bell. I showed them this lovely doodle from the rough minutes of a Society meeting:

while relating how Halley, in his own words:

‘had contrived [a] way to goe out of the diving bell, and stay in the water as long as he pleased […] by a Vessel, a man may carry on his head like a cap and by forcing him with bellows, or such like means the Air contained in the diving bell, whereby he might goe all round about it for a circle of 4 or 5 fathom radius'.

Coral structures were also included in my show-and-tell session, in the shape of Charles Darwin’s book The structure and distribution of coral reefs, the inspiration for the 1890s expeditions to Funafuti discussed in my colleague Jon Bushell’s recent blogpost. The main star of the show, though, was the material I put on display from the most significant oceanographic research voyage of the nineteenth century: the 1872-1876 Challenger expedition.

The Challenger was a converted Royal Navy ship carrying a crew of almost 250, including a six-person scientific team led by Charles Wyville Thomson FRS. The Royal Society set the scientific programme for the voyage, via its Circumnavigation Dredging Committee (the ‘dredging’ was soon dropped from the title), although as Erika Jones of the National Maritime Museum points out in her excellent recent book, available on our Library shelves:

‘Challenger’s experienced navigational officers had other reasons to explore the deep sea: the UK Hydrographic Office had given them clear instructions to survey the depth and nature of the ocean floor to support the laying of submarine telegraph cables, a rapidly expanding communications network vital to the commercial and military interests of the British Empire.’

Whatever the motivations for launching the lengthy voyage – nearly 69,000 nautical miles in length and three-and-a-half years in duration – it was a huge success, establishing the basis of the modern science of oceanography and documenting almost 5,000 species previously unknown to science. One of our current Fellows, Graham Bell FRS, in his 2022 book Full fathom 5000 (also in our Library loan collection), focuses on these newly-discovered creatures, complete with chapter subheadings such as ‘A cosmopolitan cucumber’, ‘A fierce scallop’ and ‘An enigmatic polyp’. Another one to add to my reading list!

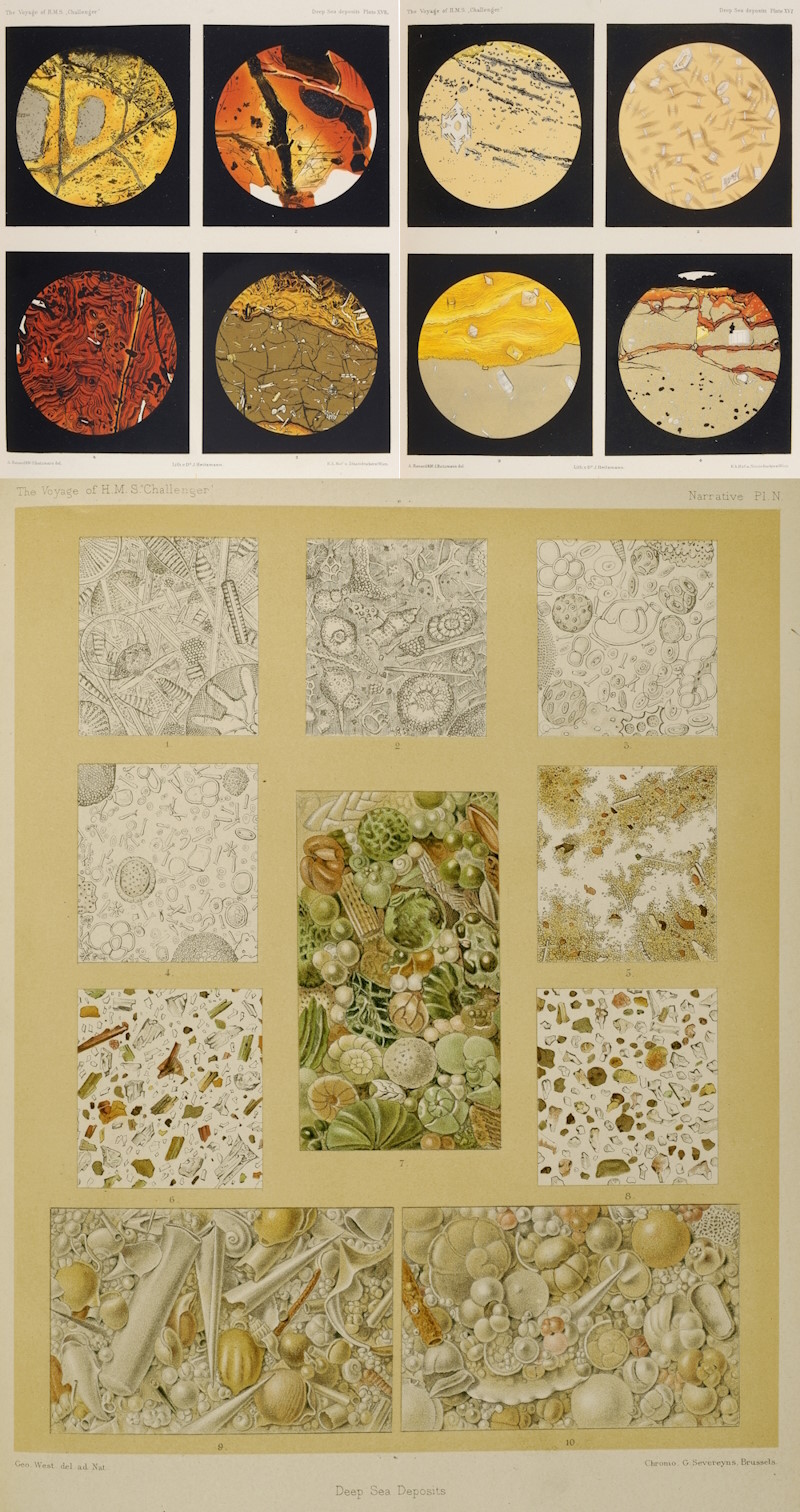

I treated my tour group to a selection of illustrations from the Report on the scientific results of the voyage of H.M.S. ‘Challenger’, and will share a couple here, from the colourful ‘deep sea deposits’ section:

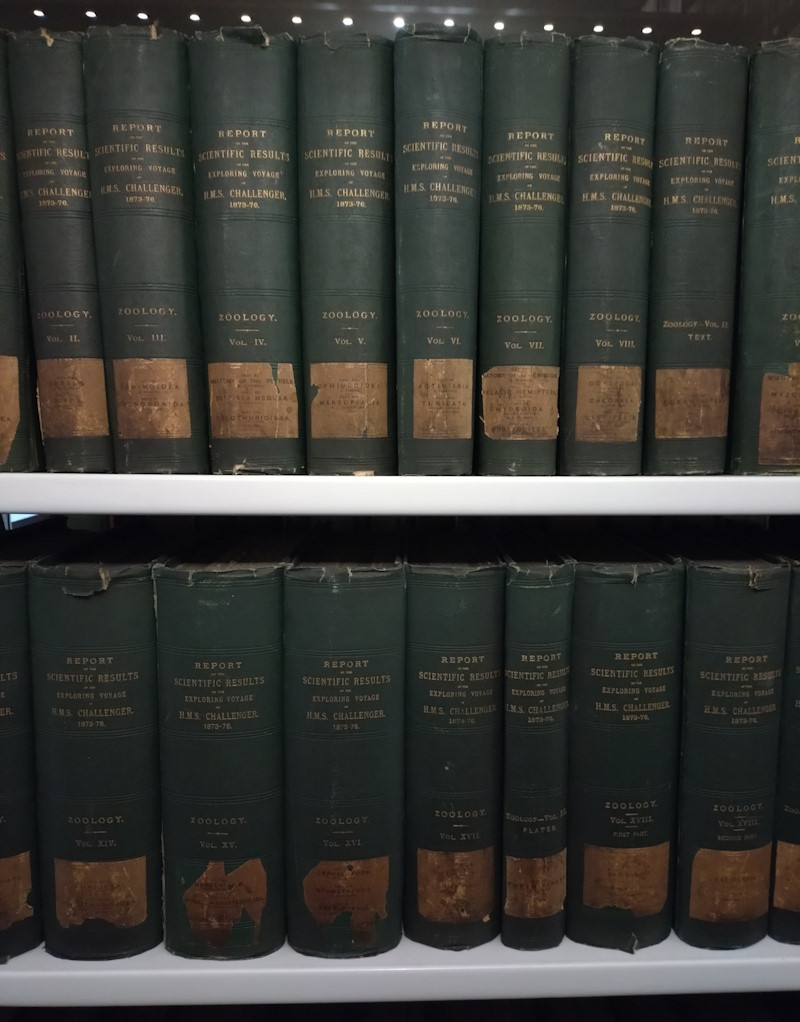

However, a half-hour show-and-tell session in the Library, on a few smallish reading room desks, was only enough time and space to showcase a fraction of the mammoth Challenger report, which stretches to 50 volumes and nearly 30,000 pages. We have the full set tucked away in our dimly-lit underground vaults – the rolling stacks don’t open wide enough to allow a single photo of the whole set, but this will give you an idea:

If your research areas overlap with the Centre for Seabed Mapping team and you’d like to see any of the items mentioned above, then do book a place in the Library during our weekday opening hours. And if you’re tempted by a bespoke Library tour, let us know your interests and we’ll see what we can do – we’ve hosted recent visits on themes as diverse as astronomy, pioneering women Fellows of the Royal Society, mathematics, Michael Faraday and South Korea, and we’re always up for a challenge!

A version of this post will also appear on the website of the International Commission of the History of Oceanography, as part of their series on archives of interest to historians of the ocean sciences. Follow the links for Erika Jones’s piece on the National Maritime Museum, and for articles on the Polar Archives and Vanderbilt Museum in the United States.