A new collection in the archives of the Royal Society shows how the electrical engineer Alan Archibald Campbell Swinton FRS was an active debunker of junk science and the paranormal.

In the cold, dark days of December 1708, something was stalking the farms of Upminster, in Essex – rattling furniture, banging doors, and pulling the bedclothes off unsuspecting citizens. The investigator of this unearthly visitation would be the local rector, William Derham FRS (1657-1735), one of the Society’s own team of historical Van Helsings.

Considering that the Royal Society is an evidence-based, scientific organisation, you may be surprised to learn that our Fellows’ writings do sometimes stray into ghost story territory. But you can’t keep a good spirit down (especially in a Christmas blog) and they do keep this sceptic amused. Regrettably, Derham’s tale (from a letter to Hans Sloane FRS) had no resolution; we never get to learn if it became a prequel to The Exorcist, although I suspect a windy night and a poorly insulated bedroom. And if having the duvet yanked away from you in the middle of the night is a measure of paranormal activity, then I must live in the most haunted house in England.

Derham wasn’t alone in regaling his scientific peers with tales of apparitions. The letters of Martin Folkes (1690-1754), later a President of the Royal Society, contain a tale from 1735 about a predicted death from beyond the grave, while in 1710 the American puritan and natural philosopher Cotton Mather FRS (1663-1728) gave a chilling account of a murder victim denouncing his killer to a sibling:

‘…his brother appeared now unto him, having on him a Bengal gown, which he usually wore, with a napkin tied about his head. His countenance was very pale, ghastly, deadly; and he had a bloody wound on one side of his forehead…’

Ghosts, it seems, were quite the thing in the eighteenth century, and (one suspects) just as entertaining for the listeners at Royal Society meetings as they are today. But if you think things had moved on since the Enlightenment, then you’d be wrong: the thing about revenants is that they just won’t lie down. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw rising interest in spiritualism and seances, including an attempt by one Mrs Roy-Batty (insert ‘I've seen things you people wouldn't believe’ joke here) to have a paper on plaster casts of ectoplasmic disembodied arms published by the Royal Society.

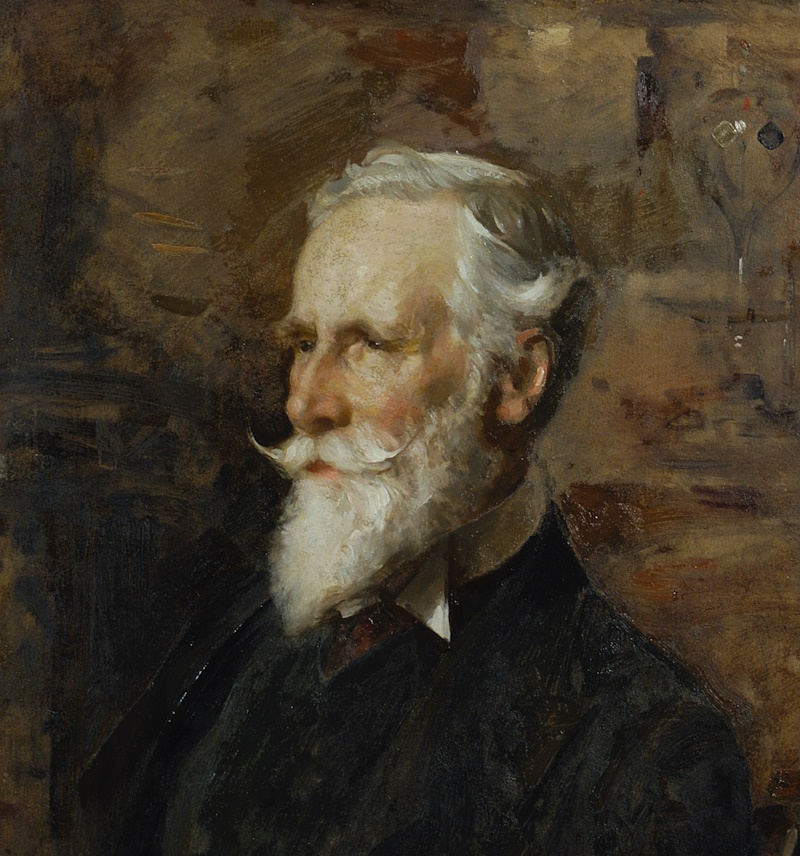

William Crookes, by Edward Arthur Walton, 1911 (RS.9243)

William Crookes, by Edward Arthur Walton, 1911 (RS.9243)

That was as late as 1924, the same year which marked the retirement of the egregiously fraudulent ‘medium’ Anna Eva Fay (1851-1927) who had hoodwinked William Crookes FRS (1832-1919) into believing in the ghostly Katie King some fifty years earlier. Crookes was a gullible viewer of so-called ‘spirit photographs’, but the Royal Society could field an altogether more clear-sighted Fellow to rebut this particular strand of fakery. Who you gonna call? Well, Alan Archibald Campbell Swinton FRS (1863-1930). My colleague, Vida Milovanovic takes up the story…

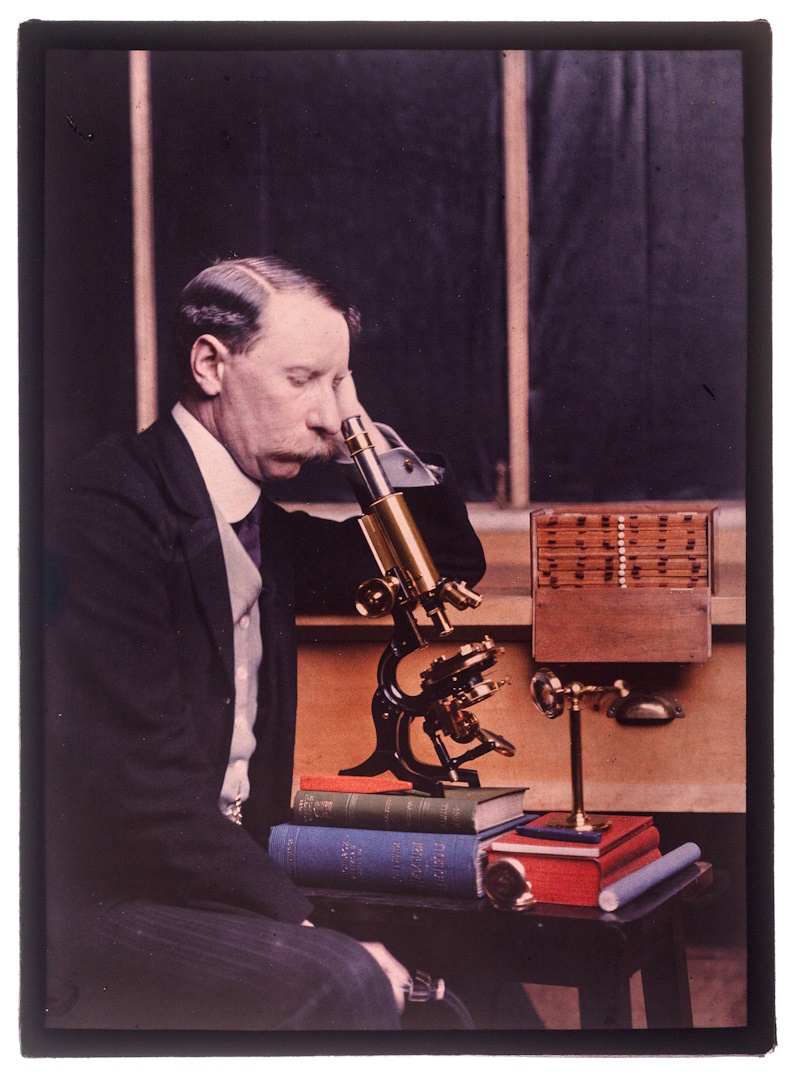

Colour glass plate portrait of Swinton (ACS/6/2)

Colour glass plate portrait of Swinton (ACS/6/2)

Earlier this year the Royal Society acquired the Campbell Swinton papers, generously donated by the Swinton family. As well as being a significant electrical engineer with a voracious appetite for innovation and problem-solving, Swinton was a pioneer of television (imagining an all-electronic concept for its realisation) and wireless telegraphy. From his schooldays, he was fascinated by photography and would take some of the earliest X-ray images. But as I started to catalogue his papers, an unexpected side of his character emerged: Swinton was an active and vocal debunker of junk science, and particularly anything suggesting the paranormal – a genuine ghostbuster.

Among his files, one of the most intriguing has the original title ‘Science and Psychical Research’. This contains copies of published articles and excerpts of Swinton’s public debates on the topic – suffice to say that he was less than impressed by claims of the supernatural. Intriguingly, Swinton knew two of the most interesting storytellers of this period and they both feature in his challenges to the ‘science’ of psychical research. In the first, he crossed swords with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) following a positive review by Robin John Tillyard FRS (1881-1937) of Doyle’s 1926 History of Spiritualism in the journal Nature. Swinton’s comments were typically robust:

‘It is replete with what has been rather aptly described as ‘determined credulity’… it trades on the credulous side of human nature and especially on the emotions of those who, having lost friends who were dear to them, are distressed … and … in desperation will clutch at any floating straw … the whole history of spiritualism simply reeks with fraudulent deception.’

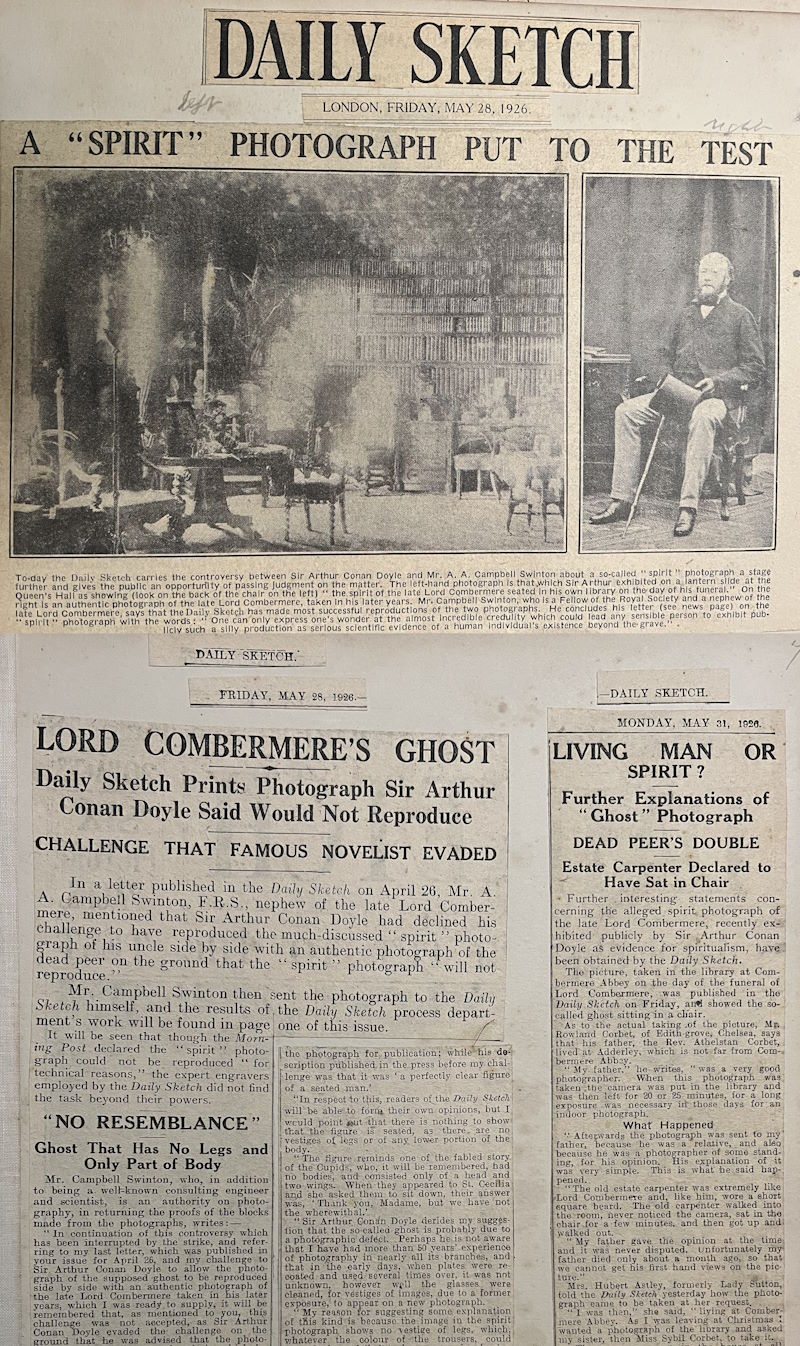

Press cuttings covering Swinton’s public debate with Conan Doyle (ACS/5/9)

Press cuttings covering Swinton’s public debate with Conan Doyle (ACS/5/9)

Swinton had previous experience of Conan Doyle’s ideas on the supernatural: earlier in 1926 the author had exhibited by lantern slide a photograph purporting to be the ‘spirit’ of Wellington Stapleton-Cotton (1818-1891), second Viscount Combermere. Swinton immediately challenged it in the press. He had already seen the image, years earlier, and indeed Combermere himself: the Viscount was a relation by marriage. Swinton could demonstrate from family photographs that the ‘ghost’ looked nothing like his uncle, and used his own expertise to suggest the likely cause of the anomaly: a simple flaw in the photographic plate.

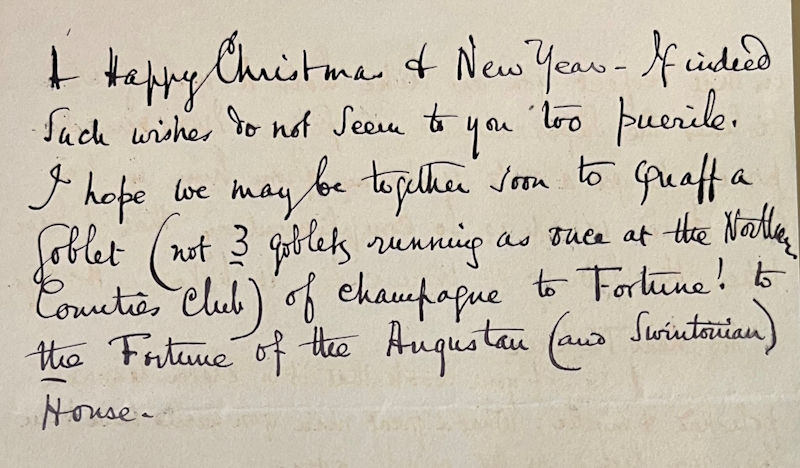

It's wonderful to see Conan Doyle’s personal letters to Swinton within our archive – he was, after all, a fine writer of fiction, if not as ruthlessly logical as his own Great Detective. Letters can also be found from another novelist: J Meade Falkner (1858-1932), whom Swinton knew through his engineering work. Falkner, the author of Moonfleet (1898) was secretary, and eventually chairman, of the giant Armstrong-Whitworth company on Tyneside. His first work of fiction was a ghost story, The Lost Stradivarius (1895), featuring an instrument which is under the occult sway of a wicked former owner. Falkner implored his friend Swinton to buy the book, and to encourage its circulation. Rather wonderfully, Swinton seems to have done just that, as his correspondent noted in a letter of December 1895:

‘This was all apropos of you reading ghost stories at night with a moonlit bay of Naples before you. It is very good of you to have bought the Stradivarius & to have read it [and] speak so kindly of it and I assure you that your criticism is valued by me especially because your habits have made you anti-supernatural to a large extent…’

A winter sojourn spent reading ghost stories overlooking the Bay of Naples? Sounds good to me – we hope your holidays are just as spookily perfect as Archibald Campbell Swinton’s!

Christmas wishes from Falkner to Swinton (ACS/1/1/150)

Christmas wishes from Falkner to Swinton (ACS/1/1/150)