Eloise Barber tells the story of Otto Loewi ForMemRS and his detention in Austria in 1938.

While auditing the Royal Society's medals collection, I came across something that sparked a deeper exploration into both history and science – the Nobel Prize medal of Otto Loewi, awarded in 1936 for his groundbreaking work on neurotransmission.

Loewi had already cemented his legacy before the rise of the Nazis. His story took a dramatic turn after Nazi Germany annexed Austria, forcing his perilous escape. As I delved into his archived papers, I uncovered not only his scientific contributions but also the personal trials he endured during one of history's darkest periods.

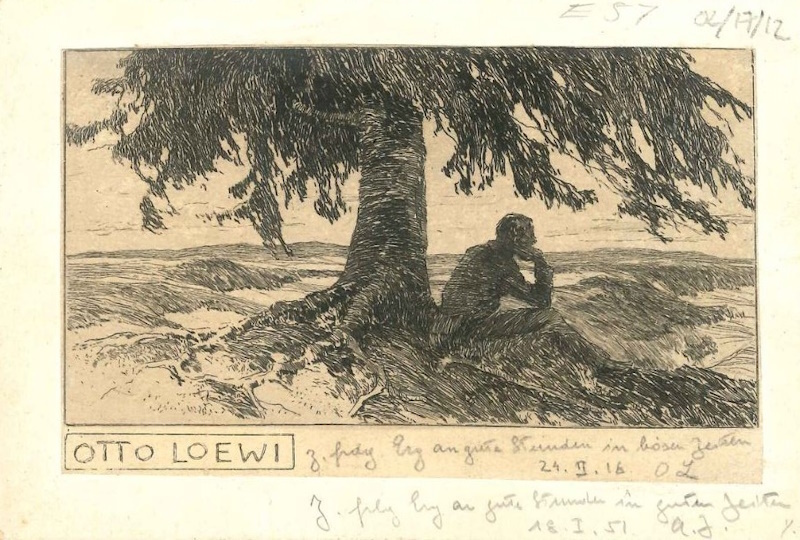

Drawing of Otto Loewi sitting under a tree (OL/17/12)

Drawing of Otto Loewi sitting under a tree (OL/17/12)

Otto Loewi was born on 3 June 1873 in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, to Jewish wine merchant parents. Loewi himself was drawn to the humanities – art, music, and philosophy fascinated him far more than commerce. However, his father’s expectations led him to become a physician, and he enrolled at the Universities of Munich and Strasbourg. While at Strasbourg Loewi was known for skipping classes to attend humanities lectures, barely passing his first year of medical exams. Initially indifferent to the field, his outlook changed by 1896, and he completed his medical degree under the mentorship of Oswald Schmiedeberg, a pioneer of pharmacology.

Disheartened by ineffective treatments for tuberculosis and pneumonia, Loewi dedicated himself to research, focusing on metabolism, protein synthesis and kidney function. In 1902, during a visit to the London laboratory of Ernest Starling, he first met his lifelong friend and colleague Henry Dale, with whom he would later share a Nobel Prize. By 1909, he had become a professor at the University of Graz in Austria, gaining a reputation as both an insightful researcher and a gifted, charismatic lecturer.

Loewi loved a good story – sometimes embellishing details for dramatic effect – and his most famous discovery certainly lent itself to legend. According to him:

‘The night before Easter Sunday [1920] I awoke, turned on the light and jotted down a few notes on a tiny slip of thin paper. Then I fell asleep again. It occurred to me at 6.00 o’clock in the morning that during the night I had written down something important, but I was unable to decipher the scrawl. The next night, at 3.00 o’clock, the idea returned. It was the design of an experiment to determine whether or not the hypothesis of chemical transmission that I had uttered 17 years ago was correct. I got up immediately, went to the laboratory, and performed a simple experiment on a frog heart according to the nocturnal design.’

His experiment proved that nerve impulses were transmitted chemically rather than purely electrically – a revelation at the time. He identified a substance, which he called Vagusstoff (later recognized as acetylcholine), responsible for slowing the heart rate. This work confirmed that neurotransmission relied on chemical messengers, laying the foundation for modern neuroscience. In recognition of this discovery, Loewi was awarded the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, alongside Dale.

While Loewi's scientific contributions were changing the landscape of neuroscience, growing tensions in Europe were casting a shadow over his personal life. In 1938, as Nazi forces invaded Austria, Loewi and his two youngest sons were arrested at gunpoint by the Gestapo, imprisoned for three months and subjected to brutal treatment.

Despite his dire circumstances, Loewi remained deeply committed to his work. Just before his arrest, he had made a significant breakthrough – the realisation that acetylcholine was absent from the dorsal roots of the spinal cord. In prison, desperate to share his findings, Loewi managed to obtain a pencil and sent a note to the Springer Verlag publishing company in Berlin. This act of defiance in the face of captivity was crucial for Loewi: he needed to get his idea out into the scientific world, even if he was unable to follow up his research.

The note was intercepted by Paul Rosbaud, a consultant for Springer Verlag and a spy for England. He passed it to Dale, who ensured that Loewi’s research reached the broader scientific community, allowing his work to continue to influence neuroscience despite his imprisonment.

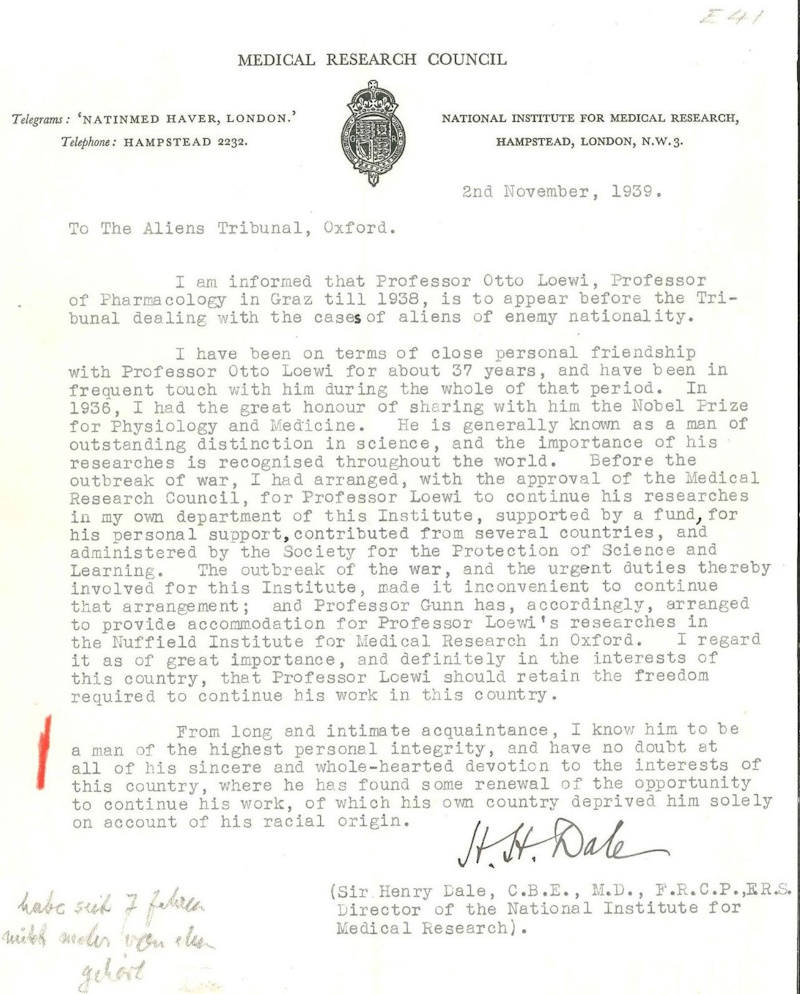

Letter from Henry Dale to the Aliens Tribunal, Oxford, November 1939 (OL/16/17)

Letter from Henry Dale to the Aliens Tribunal, Oxford, November 1939 (OL/16/17)

News of Loewi’s detention reached the International Physics Congress in Zurich, sparking an outcry from fellow scientists and friends and significant international pressure. Loewi was freed, but only after agreeing to surrender his research, possessions and Nobel Prize funds to a Nazi-controlled account. He fled Austria, reaching England in September 1938 and spending several weeks with Dale before being offered a position at the Nuffield Institute in Oxford.

In 1940, Loewi emigrated to New York. After the long Atlantic journey, Loewi handed his papers to an immigration officer and – to his amazement – was allowed entry into the United States:

‘Upon my arrival in New York harbour, a clerk prepared my papers for the immigration officer. While he was busy doing this, I glanced over the doctor's certificate – and almost fainted. I read: ‘Senility, not able to earn a living.’ I saw myself sent to Ellis Island and shipped back to Mr. Hitler. The immigration officer fortunately disregarded the certificate and welcomed me to this country.’

Loewi quickly settled, becoming a research professor at the New York University College of Medicine. There, he continued his work in pharmacology and neurobiology, collaborating with leading biologists and advancing the field of neurotransmission well into his later years.

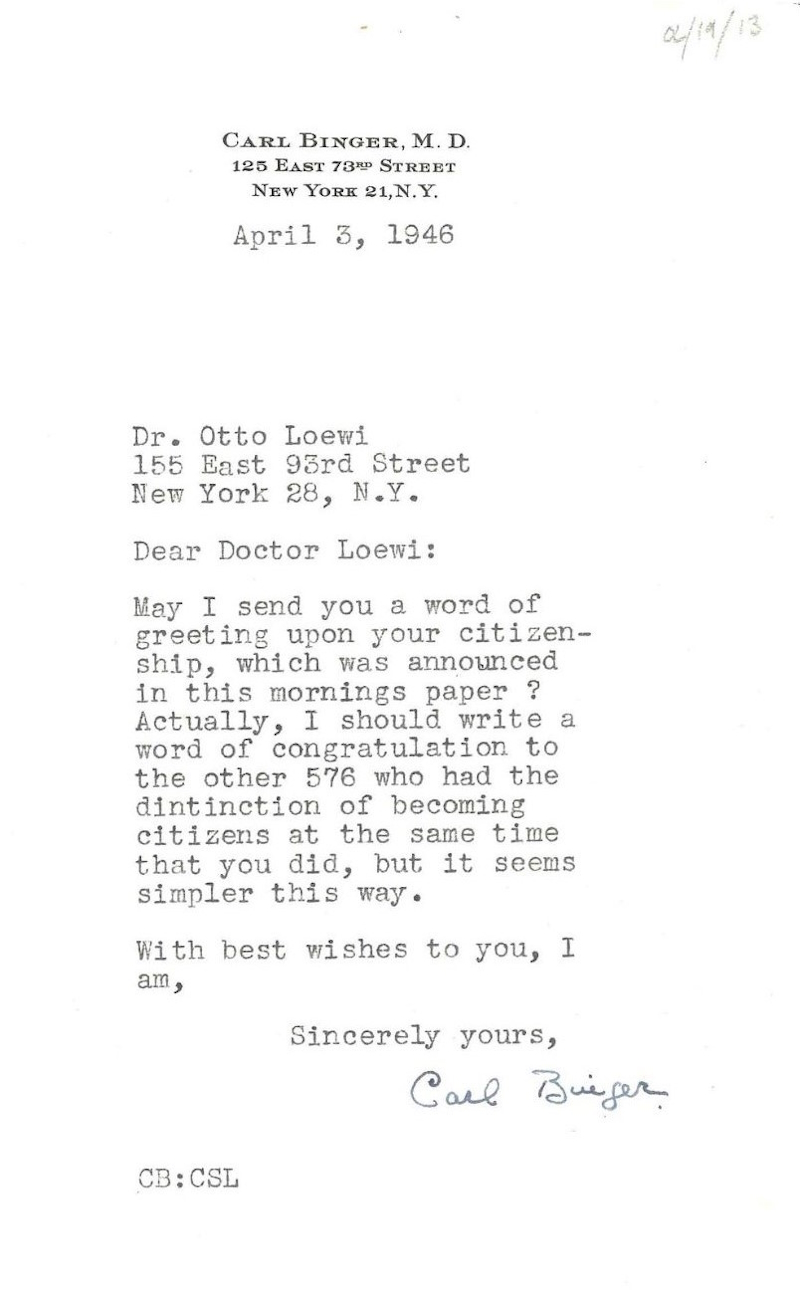

Letter from Carl Binger to Otto Loewi, April 1946 (OL/19/13)

Letter from Carl Binger to Otto Loewi, April 1946 (OL/19/13)

In 1946 Loewi became an American citizen. His remarkable contributions to science earned him many honours, including awards and honorary degrees from prestigious institutions including Yale University and New York University. In 1954, Loewi was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society. He considered this fellowship an honour equal to the Nobel Prize, as it acknowledged his lasting contribution to science.

Portrait of Otto Loewi by P Carvalho, 1942 (RS.9251)

Portrait of Otto Loewi by P Carvalho, 1942 (RS.9251)

Otto Loewi passed away on 25 December 1961, at the age of 88. After his death, Loewi’s family donated his papers to the Royal Society, where his Nobel Prize medal remains today. Loewi’s story is a testament to his enduring powers of perseverance, and the ability to overcome adversity in the darkest of times.